Have I gushed about Children of Men enough? Have I mentioned again and again how much I loved it? I saw it again just before New Year’s, and I was just as electrified the second time, and I was thrilled to see one of the bigger theaters in a Times Square multiplex almost sold out – and to see the audience respond so well to the movie.

Have I gushed about Children of Men enough? Have I mentioned again and again how much I loved it? I saw it again just before New Year’s, and I was just as electrified the second time, and I was thrilled to see one of the bigger theaters in a Times Square multiplex almost sold out – and to see the audience respond so well to the movie.

Children of Men isn’t an easy film; it’s not light entertainment. But it is entertaining and involving and it’s filled with images that are so seared into my mind that I can close my eyes and see them perfectly. It’s the sort of movie that comes along just when you need your faith in filmmaking – as art and craft – restored.

And it’s opening wider this weekend. It opens in 1200 theaters on January 5th (which, depending on when you read this is tomorrow or today), which means it is almost surely playing at a theater near you. Go and see this movie! You’ll be glad you did.

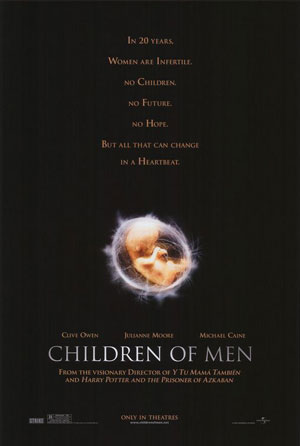

A couple of weeks back I ran my exclusive interview with Children of Men star Clive Owen (click here). Now it’s time to share my interview with the film’s director, Alfonso Cuarón. Most of you remember him from Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, which was without any doubt the best film in the series. You may also remember him from Y Tu Mama Tambien, a wonderful grown-up movie that introduced America to Diego Luna and Gael Garcia Bernal. I guarantee to you that after this weekend you’ll always think of him as the director of Children of Men.

This interview, which I found very illuminating, contains mild spoilers which I have not blacked out.

I was talking to Guillermo del Toro about how much we both love this movie and he made me promise to ask you how you accomplished those long shots. He said you wouldn’t tell him.

[laughs] The things is Emmanuel Lubezki – “Chivo” – made me promise that we were not going to reveal how we did the shots until after the release of the film. The reason is for Chivo it isn’t the technical aspect – it’s the conceptual problem. What we were trying to do with the film is create moments of truthfulness in which the camera just happens to be there to register this moment. Chivo feels that as soon as we call attention to how we did this, the focus won’t be on the moment of truthfulness but how you register the moment of truthfulness.

When did you decide on doing these extraordinary long shots?

From the get go. What we talked about is that even if this was a movie with better cameras and more production values than Y Tu Mama Tambien, the approach was going to be exactly the same. That means a character is as important as his environment. There’s a lack of close-ups because we want to weight the environment with the same weight as the character. We tried to respect as much as possible the notion of real time, and not to use editing montages to seek an effect. That was the point of departure from the very get go. Except that in Y Tu Mama Tambien it was about two or three characters talking and maybe having sex and the social environment of my country, and in Children of we had to recreate a social environment and going into situations in battlefields and war.

I had a friend who saw Children of Men and said to me, ‘Did they film this yesterday?’ The film feels so relevant to what I read in the paper this morning. Can you talk about how you approached the film in order to make it so relevant?

I think one thing is the thematic element of it. When you see images of people arriving to the refugee camp, you associate it with images of – I hear people refer to it as images of concentration camps in the Second Great War, but the visual frame of reference was Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. But the essence is the same. It is how people are oppressing other people and what people are doing to other people – thematically it’s relevant. From the standpoint of iconography, we tried to update the whole thing as we shot it. We tried to keep it relevant. We tried to make an observation of what is crafting this first part of the 21st century. Chivo kept on saying, ‘There cannot be one photogram in this film that does not reflect the state of things.’ That was the toughest thing about making this film, the constant questioning of, is this shot, is this photogram reflecting that state of things, or are we missing the opportunity to talk about something?

With Harry Potter and with Children of Men you have these big budget movies that have special effects and big action scenes, but in both films – when Harry is riding Buckbeak, and in this film when they’re taking the baby out of the building – you build in these moments of grace and beauty that most films don’t stop to acknowledge. How important is it for you as a filmmaker to hit that note?

There’s something really mysterious in film – I guess in all the arts, but film is the thing I feel more familiar with. It’s the mystery of film by which trying to convey something in a realistic way, you try to get into more hidden mysteries and spirituality. It’s not about trying to make pretty shots or beautiful moments or beautiful moments with music. More and more I am getting concerned with the conceptual aspect of things. Early on in my films I felt that this was achieved formally, but now I am getting convinced that this is achieved conceptually and thematically.

How does that work – when you try to achieve these moments of spirituality, where do you begin?

When I decided I wanted to do this film, everything came out of an image, an image that is not even in the film. The image that I had as the point of departure was a pregnant, naked woman walking through a battlefield filled with riot police and somehow the battle would stop and everything would part – the description was, ‘As the Red Sea parted as Moses walked.’ For me that was the point of departure – the conceptual conflict between the vulnerability and the purity of a naked pregnant woman in concert with the high technology of the machinery war.

In a lot of ways Children of Men is a dark film, it’s a dystopian film – but it’s also a hopeful film. Do you have hope for the future? We’re in a very grim place right now, but do you think it can get better?

I have a very grim view of the present but I have a very hopeful view of the future. The reason is that I have a hopeful view of the evolution of human understanding. It’s an evolution that I am certain is happening right now – maybe not with my generation, but with the youngest generation, and the generation yet to come. I don’t think that any solution can come from the ideology of politics, but I think we can find new ways through different understanding. When I talk about understanding, I don’t mean that suddenly the world will become a hippie commune with flowers and peace and love and swimming naked in the river – I think that human nature will keep on being human nature, it’s just that we’ll learn how to cope with that nature.

How did you decide on Clive Owen? After watching the film I really can’t imagine anyone else in that role.

I tell you, the film works because of Clive. Every single thing is on Clive’s shoulders. For the audience, Clive is the emotional vessel. Maybe he doesn’t seem like it, but he’s such a difficult character to play, because he’s against the rules of a conventional movie character. In a conventional movie character, your hero is making the choices, he’s making the decisions. Our character is actually avoiding any responsibility. Our character represents the social and emotional immobility of contemporary humanity. He has to be socially and emotionally mobile – there has to be a life going on. I think there are two things: one is the compassion [Clive] brings, and the other is the constant sadness, the sadness of a character who has lost hope. I think the film has two different lives. One is taking the girl to a safe place – that’s the least interesting of all. Then there’s the thematic life, the story of the state of things, using the social environment to tell the story of the state of things. Part of that is the spiritual journey of Clive Owen’s character, which is a character who tried to change the world in his youth and who gave up when reality became bigger than his desire for change. He, at the very end, recovers his sense of hope.

One of the reasons why I want to see Children of Men again is that every frame is full of information – every shot is so dense. But there’s one scene, where Theo goes to get the transit papers and we see a big floating pig out the window. That’s a tip of the hat to Pink Floyd.

Totally! Totally!

What is it about that scene that made you want to reference Pink Floyd there?

It’s the whole creative process, which from the script it was suggested that the location was going to be Battersea Station, which was a reference to the Tate Modern. When we decided it was going to be Battersea, when we were writing the script we were listening to King Crimson, the music we were going to play there. The thing is when we were framing Battersea Station, I looked at the frame and I said, ‘Wait a minute, something is wrong. Something is missing.’ And what was missing was the pig! That’s when we decided to add the pig to the whole thing.

What’s next for you? Is it Mexico ’68, about the Tlatelolco Massacre in Mexico City?

I don’t think so, because I have to do so much research for Mexico ’68. And more importantly, after doing this film, which has so many massacres, I need a break from massacres.

Do you have any idea what’s next?

Something very small in Mexico, I think.

Whatever it is, I can’t wait. I really think Children of Men is one of the best films I have seen this year.

A friend of mine, Carlos Reygadas who directed Battle in Heaven, said to me that he stopped believing in films that stop when the lights come on. Now I only believe in films that start when the lights come on. It’s great to have this conversation with you and see what the film has brought out of you. It’s making my day!

Going back to my first question, one of the other great films of the year is Pan’s Labyrinth.

Isn’t it amazing?

I feel like you and Guillermo both make films with that spiritual grace. You never see that anymore.

You know, Guillermo and I have been talking… the most conventional way of doing film is plot oriented film. Then you have the other, if you’re being less mainstream, is the character oriented. But there’s another element – thematically oriented. It’s about allowing the audience to partake with the film and draw their own conclusions.