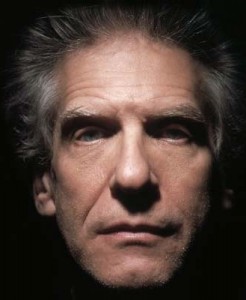

When you talk to a man like David Cronenberg, you’re talking to an artist that has not only been consistently working for several decades, but has remained relevant for many decades- much more so than most of his early contemporaries. You can understand exactly why that is the case on a gut level as he speaks, simply because so many of his answers about his process boil down to confidence and mastery.

When you talk to a man like David Cronenberg, you’re talking to an artist that has not only been consistently working for several decades, but has remained relevant for many decades- much more so than most of his early contemporaries. You can understand exactly why that is the case on a gut level as he speaks, simply because so many of his answers about his process boil down to confidence and mastery.

In other words, David Cronenberg just knows how to make a movie.

In this interview Mr. Cronenberg and I speak at length about how he visualizes, shoots, and assembles his films, before hitting on the place his career has reached creatively. He has some extremely interesting and lengthy answers to each question, and I can honestly say this is one of the coolest (though painfully brief) interviews I’ve ever been lucky enough to conduct. I’m bummed he didn’t have time to dive deeper into my final question, but there’s some really good stuff in this interview, so check it out.

++++++++++++++++++

A Dangerous Method can be seen in limited release currently, and you can watch the website for news of it coming to your town. Read Joshua’s review of the film here, and look for mine coming imminently (video quick review here)!

A Dangerous Method can be seen in limited release currently, and you can watch the website for news of it coming to your town. Read Joshua’s review of the film here, and look for mine coming imminently (video quick review here)!

++++++++++++++++++

Renn: You avoided the title “The Talking Cure” because it didn’t quite have a cinematic ring to it, and yet this film is developed from a screenplay filled to the brim with psychotherapy shop-talk… did you have any fears that the density of it would make it less palatable to film audiences- or was that at least a consideration you were cognizant of?

Renn: You avoided the title “The Talking Cure” because it didn’t quite have a cinematic ring to it, and yet this film is developed from a screenplay filled to the brim with psychotherapy shop-talk… did you have any fears that the density of it would make it less palatable to film audiences- or was that at least a consideration you were cognizant of?

Mr. Cronenberg: Oh no, that was the attraction for me [chuckle], in fact, I think [writer Christopher Hampton] was a little surprised by that. First of all, I have to say I don’t think heavy dialogue is theatrical just on its face, you know? For me, what I shoot most as a filmmaker is faces talking. So to me, a person talking–especially if you have a fantastic face saying amazing things–that’s innately cinematic, that is not theatrical. Especially of course, in close-up, which you can’t do in the theater. So I didn’t really worry about that at all, it wasn’t remotely a concern because the play was called “The Talking Cure” it was about talking, but to me that’s what was attractive about the people. They were so incredibly articulate, so well-educated, and so obsessive about saying everything, holding nothing back- no secrets, no vulnerabilities. That was what was exciting about the people, and their invention of psychoanalysis, which was the same thing basically. The idea of psychoanalysis is that you say everything and you don’t hold back anything. So, in other words, no. On the contrary it was one of the attractions to me of the script and of the project in general.

Renn: I feel like a lot of the “cinema” of the film came through the very deliberate pacing, editing, dynamic frames built from actor blocking, split-focus shots, and the temporal jumps that happen throughout, so tell me about your process of engineering how such a sophisticated film was going to look and feel.

Mr. Cronenberg: Sure. Well, I don’t do storyboards, and when I come to the set in the morning I just clear everybody off the set except for me and the actors and then we start to block the scene: we figure out how the actors are going to move, and where they’re going to say their lines, and how they will say their lines. I don’t do rehearsals. So for this process that is the beginning. The first time I actually hear the dialogue spoken is at that moment, the morning that we’re going to shoot that scene.

Renn: Oh, wow.

Renn: Oh, wow.

Mr. Cronenberg: Yeah. Now, of course you’ve done a lot of prep at that point because you’ve cast the actors, you’ve worked out the costumes, you’ve worked out the props, you’ve either designed the set and set decorated it or you’ve chose the location, and so on. So it’s not as though you haven’t done any prep but, for example, in the scene with the galvanometer (the sort of “lie detector thing), there was a lot of prep in setting up that little room. For example you have an idea what time of day it is… through the window you can see Lake Zurich. The natural elements of the film are actually quite important, and the sunlight and the daylight are actually quite important, given that it’s a film that takes place in a lot of rooms often, although there are exteriors obviously. So you’ve done all that, but by that point I still don’t know what lens I’m going to use, where the cameras gonna be, I haven’t really talked in detail to [Director of Photography] Peter Suschitzky about how we’re going to light it- all that happens spontaneously and intuitively on the spot. And, you know… that’s the way I work, and that gives the actors huge input into how the scene will play.

You know, if you do storyboards- storyboards are usually done before you even cast the movie, so you’re really moving the actors around like pawns, and saying “do it like the pre-viz,” and I’ve never understood the attraction of that, other than that is kind of a security blanket. You’re not gonna worry, “oh, what if I come on the set and blank out and just don’t know how to shoot it.” But for me that’s part of the excitement. “It’s okay, let’s try and figure out how we’re going to do this scene today.” That’s how I’ve always worked actually.

Renn: You’ve worked with Mr. Suschitzky for a number of years, so I must imagine you have a shorthand or a comfortable dynamic at this point. Does that free you up to have that spontaneity on set?

Mr. Cronenberg: Well, what it is is we like the way we work, you know, it’s the same. Peter- obviously he has to order his lights and he has to order his camera equipment, and he can say to me, “do you think we’re going to want the split-focus lenses or not?” and we sort of anticipate that, so you have your camera package. And then he’s involved when we’re designing the sets, so- “okay, what are the sources of light?” In this case. did they have electrical lighting in the Burgholzli Clinic or was it still gas light, because it was in a transitional period from one to the other… that kind of thing. So he too has done that kind of prep, but basically though, everything else is up for grabs when we’re deciding how we’re going to do the scene.

Renn: So I understand how it fits into your process of spontaneously visualizing and blocking a scene to not have rehearsals, but what, specifically in terms of the acting results, attracts you to hearing the dialogue for the first time on set, and not in table reads?

Renn: So I understand how it fits into your process of spontaneously visualizing and blocking a scene to not have rehearsals, but what, specifically in terms of the acting results, attracts you to hearing the dialogue for the first time on set, and not in table reads?

Mr. Cronenberg: Well I tried that once, actually, when I did The Fly. I hated it, and I found it to be completely useless, because as soon as you get on the real set [chuckle] everything changes. You know, there are a couple of things… Of course sometimes you just don’t have access to that actors–they’re busy, they’re working–so what do you do if you have two out of the three actors in the scene? Do you still go ahead with the rehearsal with you reading the other persons lines? You could do that, but for me, I found that everything changes when you have the actors in the costumes on the real set and you’re not just sitting around the table, and the game is on and the pressure is on. Everything changes. So I found that all the work that we did sitting around that table when we did The Fly… it just went out the window! It was counter-productive actually, and I found it to be a waste of time. Now I know there are actors who love that, and I remember talking to Paul Giamatti- we were on the stage together, in Estero actually, not long ago in Portugal. He said he really enjoys rehearsing, but he also didn’t have a problem doing it the way I was doing it, so ultimately it has to work the way the director wants to do it because he’s going to be working with all the actors, and each actor has a different thing, you know? Each actor is different and needs different things, but I’ve never found this to be a problem.

Renn: So you talk about making a film so filled with great actors saying great things, which obviously gives you a lot of power in the edit. How hands-on do you get with your editor during post-production, and to what degree do you consider the edit as you’re shooting?

Mr. Cronenberg: Well I consider the edit all the time while I’m shooting. In fact, I’ve gotten more and more concise and I’ve finished days early on Dangerous Method and about six days early on the last film I did, Cosmopolis. I just simplify, and I don’t need to cover myself as much. In fact Peter has told me I shoot very differently from when I did when we first did Dead Ringers in 1988. I just don’t feel the need to cover the whole scene from every angle. So, like, I’ll just do a close-up for the last two lines of dialogue if I think that’s all I’m going to use it for, and I don’t have any worries or second guessing myself on set, and that seems to work pretty well. So Ron Sanders–who I’ve worked with for over 35 years–he’s cutting while I’m shooting, and I don’t want to see anything. There are directors who edit at night or on the weekends and work with the editor, and I don’t want to. I don’t want to see the movie, I want to forget what I’ve shot and then a week after we finish shooting he shows me his assembly– he doesn’t even want to call it a rough cut–and then that’s the most objective look I’m ever gonna get of the film, you know, because then I start to get very familiar with it. That’s why I want to kind of cleanse my mind of what I did and be surprised at what I did and just see if it works or not. I try to watch it like I’m watching someone else’s movie, in other words. After that I go in and it’s a very short period of time before I have a director’s cut. I think with Dangerous Method it was about seven days, and with Cosmopolis it was two days.

Renn: Wow.

Mr. Cronenberg: And by “director’s cut,” well, what do I mean? I mean it’s a cut I’m willing to show my producers and say, “this is the movie that we’ve made.” It doesn’t mean that I don’t trim it a bit here and there in the following weeks, but basically that’s it. Seven days, two days. I think for Eastern Promises it was maybe… two weeks, so it’s getting tighter [chuckle]. But I can tell you, for example, the sauna scene- the Turkish bathe scene in Eastern Promises, I didn’t change one frame from what Ron cut in his assembly. What he cut, what I first saw, was ended up in the final cut.

Renn: That’s incredible. Such a huge scene…

Mr. Cronenberg: Yeah, and it’s partly because we understand each other, it’s partly because I know what I want and I don’t need any extra stuff. So, on one level he doesn’t have as many choices to make because I don’t give him those choices, and then on the other hand he really just knows how to finesse something that I’ve shot. It’s that relationship, it’s very efficient and very tight.

Renn: So there’s been a lot of talk about your recent films, and how they represent a big change for you as you’ve challenged the idea people were fixated on about what kind of director you are. I feel Dangerous Method is completely in continuity with all of your work, but it does feel like a distillation, a refinement of your ideas and sensibilities. Has this at all been a decided result of your choice of projects, or just a result of what projects have interested you and actually come together?

Renn: So there’s been a lot of talk about your recent films, and how they represent a big change for you as you’ve challenged the idea people were fixated on about what kind of director you are. I feel Dangerous Method is completely in continuity with all of your work, but it does feel like a distillation, a refinement of your ideas and sensibilities. Has this at all been a decided result of your choice of projects, or just a result of what projects have interested you and actually come together?

Mr. Cronenberg: The last thing is the reality. I don’t really think about the arc of my career or anything like that, in fact, when I decide to do another project it’s as though I’ve never made another film- other than the craft, other than my confidence in the craft. Thematically or structurally or dramatically, it’s as though this is my first movie and I’m only focused on what this movie tells me it needs and what it wants to be good, and all the other movies are irrelevant at that point. They really have no bearing on it. It’s hard for fans, and also critics, to understand that, but it’s exactly–creatively inside and out–how it feels to me. So I don’t care- you know, body horror was not anything I concieved of, it’s not my phrase. So, do I worry about? I can not- it’s of no consequence to me. It’s of interest, but I mean creatively it’s of no consequence to me.

And it’s also rather charming that people think you can pick and choose what movies you’ll make when, and say, “hey, gee, at this point in my career I think I should do this,” because it’s so hard to get a movie made, it’s so hard to find a project that it’s going to keep you awake for the two years it takes to make it and release it. It would be nice to have that ability to just pick and choose [chuckle] but it’s not like that. I remember long ago that people said to me, “well, why now? Why did you make Dead Ringers?” because of course Dead Ringers was not exactly like the so-called “body horror” films, even though it has some psychologically horrific stuff in it that was based on a real story and is relatively realistic, as opposed to sci-fi or something. “Why did you choose now to make this movie?” Well actually I’d started making the movie ten years ago, and I would have made it then in 1978 instead of 1988 if I had been able to get the financing together and I had been able to get an actor who would support the financing, but it didn’t happen. So, it’s really when the financing comes together rather than making a definitive choice to make this movie. You know what I mean? That’s the reality of the movie business.

For example, Cosmopolis just came to me by surprise, literally out of the blue! A Portugese producer who’s very well known, descended on Toronto to meet me and handed me this book by Don DeLillo, and two days later I said, “yeah, I want to make this into a movie.” Before he handed it to me, I had no idea that I would be interested in that thing. So that’s the reality of it and in terms of… I can step back and be an analyst of my own work, and I can say- well look, Freud’s revolution, what was it? In one sense it was his insistence on the reality of the human body at a time, in an era when that was really being denied, in what we would think of as a Victorian era where there was a lot sexual repression, people didn’t talk about sex, and people certainly didn’t talk about anuses and vaginas and orifices and things that Freud was talking about. So, if you think of Freud’s revolution as saying “the body is what we are, and we really have to come to terms with it because all of those body parts and things that we try to ignore actually have a huge impact on what we do and say, and even the politics of our country,” and so on and so on… When you think of it that way, and then you think of the old days, my saying, “the first fact of human existence is the human body,” then you can immediately see the connection between this movie and those other movies, even though dramatically it’s not the same genre.

Renn: Well there you go! You’ve provided us critics with a sort-of origin story of your work that can be fit into the “auteur narrative.”

Renn: Well there you go! You’ve provided us critics with a sort-of origin story of your work that can be fit into the “auteur narrative.”

Mr. Cronenberg: Exactly, yeah.

Renn: I think a lot of fans, myself included, do enjoy the idea that you’ve not totally turned away from quote-unquote “body horror” as you’ve discussed the The Fly sequel you wrote, even if Fox isn’t necessarily making that happen right now. But what, in general, might attract you to reexamining your older work? Is adding new themes, or seeing if the old themes have something new to say?

Mr. Cronenberg: Unfortunately I think we have to wrap this up soon and that’s a big subject, but basically I don’t really look at my old stuff, and The Fly thing was in fact more of a sort-of reinvented sequel that wasn’t really a remake. But really, just in terms of my fans and stuff, I haven’t turned my back on anything. I would have no qualms about doing another horror film or sci-fi film if it was of real interest to me or I thought it was of really high quality. The problem is a lot of the stuff, and this is not an ego thing just a reality, is that a lot of the scripts I get have been so influenced by my own movies that it would be like doing them again, and why would I do that? It’s just boring [chuckle], but in general I don’t feel I’ve close the door on anything, no genre, no subject matter. If I live long enough to make a thousand movies, you could imagine I’d be all over the place. I have a lot of interests, and of course as you get older you absorb and you learn a lot of things and your perspective on things changes and that’s all really interesting for a filmmaker, for an artist of any kind to come to grips with. So I don’t think the fans should be too upset. I think what it is they remember when they were terrified at the age of 10 when they accidentally saw Scanners, and they have affection for that moment, and they want to relive that, you see. But I can’t provide them with that [chuckle], they’re going to have to get that from someone else.

Twitter

Comment Below

Message Board