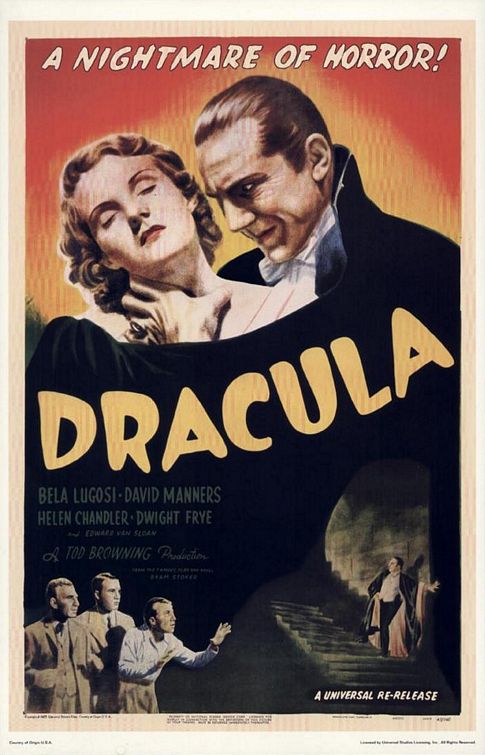

Amazingly, and forever to its credit, Tod Browning’s 1931 adaptation of Dracula has retained its freshness after eighty years (!) of being used and reused and copied and recycled and parodied. This rendition of the book takes plenty of liberties with Bram Stoker’s source material; it is totally stylized and somewhat messy and is not in the least bit boring.

There have been thousands of Dracula movies and characters since, but you know the one I’m talking about: It’s the movie with Bela Lugosi standing on a cobwebbed staircase, intoning: “Listen to them… Children of the night… What music they make!” The one where he turns into a bat! But I’ll get to that part in a minute.

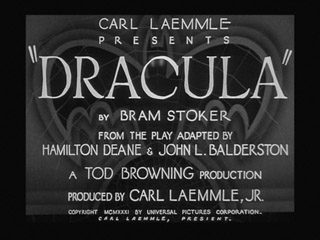

Dracula opens with a credits sequence that is already heavy on the style: a title screen serves as the backdrop that looks for all the world like the Bat-signal.

Then we’re dropped into Transylvania, where Renfield (Dwight Frye) – not Jonathan Harker – is searching out the mysterious Count. Renfield meets with a couple of spooked villagers, one a large man with a large moustache that looks ready to jump off his face, who warns that Dracula can turn into a wolf or a bat. (This movie is way into the bat thing from the start!) The villager’s wife – or mother, or both – implores Renfield to take a cross with him if he insists on visiting that dreadful Count.

Renfield enters Dracula’s castle, which does NOT look hospitable. Whereas in later cinematic iterations of the story, such as in the many Hammer recreations, Dracula’s castle is made to look like an ornate mansion that has been abandoned by its owner but meticulously kept in the interim (like L. Ron Hubbard’s office!) – the castle in the 1931 Dracula looks like a forgotten tomb. This is the movie that introduced dust and disrepair and spider-webs into the horror movie lexicon, and going back to see it in the modern day, I have to say that there is still a power behind this production design. It makes the appearance of Bela Lugosi’s well-mannered, well-groomed Count Dracula stand in stark relief to his chosen environment.

According to the terrific book on the history of horror films, The Monster Show by David J. Skal, Bela Lugosi was not the studio’s choice to play Dracula, even though he played the role on stage many times beforehand. For one thing, his Eastern European accent was genuine – Lugosi hailed from the same general area that his character was supposed to be from, and he was rumored to have very little knowledge of the English language. For another thing, he never had the conventional leading man look, if that’s even what Universal was looking for. I’m not one to judge male beauty, but it seems to me that Lugosi has more of the character’s actor look to him here, shrewd and intense (in my opinion Liev Schreiber would be good casting for any future biopics), and he was already 48 when Browning cast him in Dracula. Still, Lugosi’s Count Dracula is clearly a debonair, charismatic figure, and his first conquest here is Renfield.

Renfield is turned by Dracula into a craven, increasingly insane henchman, who books him passage to London. The voyage is shown to be horribly turbulent, and by the time the ship arrives at its destination, the entire crew is discovered dead, except for Renfield, who by now is raving mad. He is committed to Dr. Seward’s care at the local asylum. (The coffin carrying Dracula is somehow transported to land, although the movie leaves those details incredibly vague.)

The story now shifts to London, and the next time we see Dracula, he is roaming the streets, and openly attending the opera. (It’s a bit of unintentional laugh to see Count Dracula taking a ticket and being escorted through the aisle by an usher.) Dracula is then introduced to a familiar band of characters whose names and relationships have been reshuffled for the purposes of this screen adaptation. Dr. Seward is a much older man, and instead of a suitor of Lucy’s, he is cast here as Mina’s father. Lucy Westenra is given a less idiosyncratic name, Lucy Western, as is Jonathan Harker, now rechristened John. Harker’s role here is almost as a peripheral character; he remains the fiancée of Mina [now Mina Seward] but here he’s a bystander, a reactor, not much of an enemy to the Count. (Paul Rudd fans should know that this guy, David Manners, is a dead ringer.)

After introducing himself at the opera, Dracula sneaks into Lucy’s room later that night – personal note: a solitary breeze kicked open my curtains at that point in my screening – and the camera cuts away right before he pounces. Soon afterwards, Dracula’s eternal nemesis, Professor Van Helsing, arrives to make Dracula’s life hell as usual. Van Helsing is played by an American actor, Edward Van Sloan, whose implacable accent at least suggests the character’s Danish roots. Van Helsing, armed with wolfsbane (this movie’s stand-in for garlic), comes to Seward’s office to confront Renfield, who keeps devolving into a wild-eyed Peter Lorre type. Genre veteran Dwight Frye consumes his every scene with admirable dedication.

Later on, Dracula appears outside Renfield’s barred window sending him silent commands, which is a creepy scene, and then turns into a bat and appears outside the window of Mina’s room, which is not quite as creepy. All of the bat scenes suffer from primitive technology – it’s a stuffed animal being waved around at the end of a string – but I have to say that they didn’t derail my ability to stay involved in the movie. In point of fact, I kind of liked the archaic special effects. After all, this movie was made in 1931, not far from the innovation of sound in movies.

The day after his bat appearance, Dracula shows up in person, civilly, as a visitor, under the pretense of trying to soothe Mina’s nerves. There are no scenes like this in the book, or in any other Dracula interpretation that I’ve seen anywhere else, so this parlor scene was refreshing, even suspenseful. I kept waiting to see how his villainy would be revealed. As it happens, Van Helsing is present, and of course he’s the one to find Dracula out – he looks in a mirror and, where Dr. Seward and Mina remain visible, he sees no reflection for the Count. Browning definitely milks this gag more than is probably needed (there are at least three repeated mirror shots), but then, Van Helsing being Van Helsing, he abruptly shoves the mirror in Dracula’s face. Dracula freaks out, then composes himself and leaves the Sewards with the memorable line, “I dislike mirrors. Van Helsing will explain.”

Turns out Van Helsing doesn’t need to explain much – the servants come in and excitably exclaim that they saw a large wolf running away from the house. Even though that part happens off-camera, it’s by now apparent this Dracula is big on the animal transformation scenes. The Count returns again in his bat form to besiege Mina, and Renfield also keeps popping up in the strangest places – he kind of comes and goes in this movie like the wacky neighbor in a sitcom. Renfield will just wander into a room, laugh maniacally, make the maid faint, and then be warned away by Van Helsing or Seward with ripe dialogue: “You will die in torment if you die with innocent blood on your soul!” Jerry should have tried that with Kramer!

Fast forwarding, the climax of the movie is possibly the most visually striking of the entire film. Dracula finally abducts Mina and takes her to “the abbey,” which is a large hall with maybe the longest staircase I have ever seen in a film. Renfield follows, inadvertently leading Van Helsing and Harker behind him, so Dracula gets fed up and tosses him down the staircase. When they get there, Van Helsing and Harker find two coffins, one occupied by Dracula, one presumably for Mina, although she’s not in it. In a somewhat anti-climactic off-screen moment, Van Helsing stakes Dracula dead. This frees Mina of the vampiric curse. Daylight breaks, and Mina and Harker walk up that insanely steep staircase to the world outside and THE END.

Dracula is not a perfect movie – its technical imperfections go beyond the standard limitations of early cinema. According to Skal’s reporting, Tod Browning’s personal problems interfered with the filming of Dracula, and his erratic attention to continuity explain some of the movie’s jarring jump cuts and narrative loose ends. Still, the unique aesthetic vision of Tod Browning’s Dracula and its overwhelmingly widespread and lasting influence cannot be understated. Clearly I’m a person who is inclined to be fond of this kind of movie, but even I was astonished to discover how much fun it was to revisit this lively classic. If you think you don’t like old black-and-white movies, think again – you either don’t remember Dracula, or you just plain haven’t seen it yet! That’s a blind spot easily fixed with Universal’s not-too-long-ag0-reissued DVD edition. I really do recommend it.