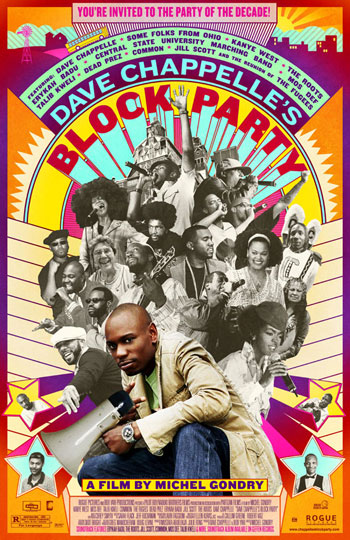

Dave Chappelle’s Block Party was shot over a year ago, in the fall of 2004, but the film has been worth the wait. Dave – before his current rounds of troubles and controversy – wanted to use his new fame to do something cool. He settled on a free concert in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, featuring some of the best and most “conscious” hip hop acts today, like Mos Def, Dead Prez, The Fugees, and a pre-superstardom Kanye West (he actually opens the show, believe it or not). Dave recruited Michel Gondry, one of the single most talented film visionaries working today, to shoot the show, but the film is more than just cameras aimed at a stage – it’s an examination of community and the worlds that Dave Chappelle lives in, from the black and celebrity filled world of Brooklyn to the very white rural area of Ohio where he grew up. Dave chartered buses to bring Ohioans to New York City for the show, including a whole college marching band.

Dave Chappelle’s Block Party was shot over a year ago, in the fall of 2004, but the film has been worth the wait. Dave – before his current rounds of troubles and controversy – wanted to use his new fame to do something cool. He settled on a free concert in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, featuring some of the best and most “conscious” hip hop acts today, like Mos Def, Dead Prez, The Fugees, and a pre-superstardom Kanye West (he actually opens the show, believe it or not). Dave recruited Michel Gondry, one of the single most talented film visionaries working today, to shoot the show, but the film is more than just cameras aimed at a stage – it’s an examination of community and the worlds that Dave Chappelle lives in, from the black and celebrity filled world of Brooklyn to the very white rural area of Ohio where he grew up. Dave chartered buses to bring Ohioans to New York City for the show, including a whole college marching band.

Meeting Gondry was a real treat – Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is one of the best, and truest films, I have ever seen. It still affects me on a deep level every time I watch it, thanks to Charlie Kaufman’s amazing script and Gondry’s astonishing touch with visuals. His latest film, The Science of Sleep, just played Sundance, and I can’t wait to check that one out – it’s the first film he wrote himself. Dave Chappelle’s Block Party, maybe the best concert film since The Last Waltz, opens this weekend.

Q: Did you know Dave Chappelle before you directed this film?

Gondry: I met him on occasion, but that was a while ago. We got to know each other six months before we started to do the concert. We had a lot of time to talk and to find out why he wanted to do that.

Q: Why did you want to direct this film?

Gondry:

I wanted to do it at a time in his career when he had a stronger power.

He wanted to use that in a positive way for all those that he likes.

All those musicians in the film he knew before. Some became major

artists, some are still more confidential. He wanted to treat all of

them equally and give them the same voice. Basically, he liked them

because they all used their music to give a message. It’s not only

about the goal of success. You could see this friendship they share.

When you see him playing at the rehearsal, he’s one of them. That’s

what was important, what interested me in doing this project. I’ve been

asked many times to do concert films, but I wasn’t interested until I

found this project.

Q: Are you a hip hop fan? Would you like to do more hip hop videos? Gondry: I love hip hop. It’s the only modern music that pushes boundaries of instruments and tries new sounds. I did some hip hop videos and tried to do more of it but it’s a system that’s not very open to the way I like to use them. Hip hop uses video to give a strong image of the artist. I’d love to do more than that. There are a few hip-hop artists that do original videos, but they’re more about the look. It’s probably because I’m not part of the entourage that it goes to somebody else.

Gondry: I love hip hop. It’s the only modern music that pushes boundaries of instruments and tries new sounds. I did some hip hop videos and tried to do more of it but it’s a system that’s not very open to the way I like to use them. Hip hop uses video to give a strong image of the artist. I’d love to do more than that. There are a few hip-hop artists that do original videos, but they’re more about the look. It’s probably because I’m not part of the entourage that it goes to somebody else.

Q: One of the things that I liked in the film is that it isn’t just a concert documentary, it also explores concepts of community. How important was that to you?

Gondry: It was important that we talk about communities and this type of music. I was very flattered that I was asked to do that, but, as an outsider, I didn’t think I could have a point of view [about] it. I don’t like documentaries that have a stronger point of view than you actually experience making the documentary. I think that you have to make the truth as you go along. The fact that I didn’t know this community so well protected me from trying anything too directive. What I knew was that, in hip-hop, images create a distance that I wanted to go across. I wanted to listen to people and [hear] what they have to say. It’s why it goes into many directions. Some people talk about prisoners; some talk about not to put blame on the white people. I think it’s good that everyone has a different voice. I think we got a positive message overall because that was what they wanted to do. They wanted to leave people on a positive note.

Q: How open were the artists? Did you find that image-conscious hip hoppers didn’t want to open up to you?

Gondry: Sometimes, they are used to [projecting] themselves on TV, [so] we needed time before they become more open. I think, whoever you shoot, you need about 20 minutes of shooting before the person forgets he’s in front of the camera. That’s a process I learned through interviews, which is the same process. They are not aware or they’re not showing off—they are simple, in a good way. In this case, they are shy and need time to open up and to be confident. Otherwise, they’re too confident and [projecting themselves] too much, so they need 20 minutes to lose that and go to the real level.

Q: Did you know that the reunion of the Fugees was supposed to occur?

Gondry: We were supposed to have Lauryn Hill, which is great. I decided we would have to relive some songs, so she suggested putting the Fugees back together.

Q: How did that change the movie?

Gondry: I don’t know because the movie was always with them. It was a danger to have the theme of the concert and the Fugees. I wanted to have them interviewed by Dave backstage because they didn’t do their rehearsals the same day. We waited a long time because Lauryn Hill was busy and wouldn’t show up. I said, “I think it’s gonna pay off.” I just wanted to have 5 minutes, but when she came, because of Dave, she opened up. She actually talked for more than that. It was important for me to have those 5 minutes to feel that it’s part of the same concert.

same concert.

Q: Is doing a documentary a departure for you?

Gondry: It’s always a departure. It was a departure when I did Science of Sleep, which I just finished. It was the first time I wrote the screenplay and was in full control of what I was saying. Here it was a departure because I didn’t have any visuals to rely on. I was asked to give a voice to people I’m not sure I know very well. It’s always scary, but I got used to deal with that. It makes me more open-minded to suggestions and to find my own truth. I don’t know what the next move will be. It’s a place where you keep your mind very aware.

Q: We see some of the concert in the film, but not the whole thing. Will there be extra performances in the DVD?

Gondry: Yes, there will be a lot more performances—it was an eight-hour concert.

Q: How much of it will be on the DVD?

Gondry: Hours. It’s going to be a very good DVD.

Q: Will there be a live soundtrack?

Gondry: Yes. I pushed all the artists to play the songs again. I pushed them to play on a smaller stage because I didn’t want the stage to be too overwhelming for the location. I knew that if it was more clumsy and crowded onstage, they would react and be happier to be together and communicative with the audience. I think the album will reflect that and would be a great opportunity to these artists. All hip-hop music is very well-produced [nowadays]. They know the machines and they push the boundaries as far as possible. It’s important for the audience to know that those [musicians] are amazing onstage. When Kenny West started the concert, he fought like a lion to get people to know that he’s a good performer. I think you’ll get that in the album.

Q: How important was it for you to do this on film, and to have it be a big screen movie?

Gondry: One of my inputs was that people just wanted me to shoot a concert. Even if it was just a concert, I wanted to have that on the big screen. When you see it in a dark room with a lot of people and you watch this good image, shot on film, and the songs are great, you feel like you’re in the concert. You won’t get that on home. I had to take it from the concert to another level to give people a voice, to follow David around, and to have a narrative. So, we went to Ohio to have the story of David giving out the tickets. We met all the characters that became part of the story, like the marching band and the people in the barbershop. All  these people became like heroes. Even the waiter was very amazing.

these people became like heroes. Even the waiter was very amazing.

I didn’t want to make a typical concert film. There’s a lot of heavy mechanics that are involved and there’s a lot of ammunition to make a very fast editing. The danger of that is that you over-cut and over-load it with fancy angles. By watching other documentary concert films that made an impact on me, you didn’t feel that all the mechanic aspects were there before. The concert was there for the audience, so I wanted to translate that. Everything is about the medium, but I didn’t want to give this impression. I looked at the camera work and noticed that it was very limited. In a way, it makes the camera invisible and gives all the power to the artist. Because you don’t cut every 5 minutes to the drummer, you feel that. We had 9 cameras on the day of the shooting, but I was ready to shoot with 2 cameras. It paid off when I edited the film because we sustained the shots as long as possible like it’s a real concert and not a crazy T.V. show.

Q: Why are there no text intros of the artists?

Gondry: We tried to do intros, but we wanted to make you feel like you’re in the movie. We used it a little bit, but to introduce each artist, it would make the flow go down. When of my suggestions was to have a backing band. You have more of a sense of community. I convinced all of them to play with the same musicians. It would have been very complicated to put text intros. I wanted to keep it organic.

Q: What was it like working with Dave? Is he a musician trapped in a comedian’s body, like he says in the film?

Gondry: I’m not sure I would put it in these words. But there is a strong resemblance with what he does in music. The way he holds the stage and tours with his little bus and when he does his comedy, it’s similar in the way that he has a specific flow that makes him unique. Generally, comedians are all about actions and reactions. He’s much more organic. By being in a communion with the audience, he doesn’t have to act with jokes. He’s like a good basketball player who changes his pace. He bursts into an explosion of energy, like a great musician. It’s not a formula that applies to every step of the way.

Q: What’s next for you?

Gondry: I wrote a story and would like to shoot it ASAP.

Q: How does writing change directing for you?

Gondry: It changes in the same way that I shot this movie. I went there with no idea with what would happen. Therefore, I was very open with what would happen next. There are so many happy accidents that happen when you just take a camera and switch it on, especially on Dave. He meets people on the street. There is magic that you can’t possible write. When I write on paper, I give some space for this magic to happen. I had to find a way to be as strong as possible to work with him. Even with Charlie [Kaufman] we leaved some room. His stories are so complex that there’s little left for these happy accidents. Writing it myself makes it more receptive to what happens that gives life to the film.

Q: Are you going to work with Charlie Kaufman again?

Gondry: I’d like to work with him in the future.

CS: How far are you on Master of Space and Time?

Gondry: I’m working on that. It’s going to take time.

Q: Are you going to keep doing commercials and music videos?

Gondry: Yes, especially music videos. The same way this film was a way to crystallize all the individual parts I did in music videos into a bigger project. It made sense at the time. I want to keep this [collaborative] experience. Music is a medium that’s faster than film. It’s a good way to keep in touch with what’s out there.

individual parts I did in music videos into a bigger project. It made sense at the time. I want to keep this [collaborative] experience. Music is a medium that’s faster than film. It’s a good way to keep in touch with what’s out there.

Q: One of the great things in the film is how Dave brings people from rural Ohio to Brooklyn for the show. Will the DVD feature more of their experience?

Gondry: Yes, we will definitely have more of that. We have 100 hours of footage on film and 50 hours of footage on video. My editor is working on that. I didn’t know about those political prisoners, so we will try to do a little subject about them. I know it means a lot for some people and I think that it’s important that the DVD will explore it. It will be hard to do justice to the problem, but at least I want to address it. One of my favorite movies is The Thin Blue Line. It gives you the sense that objectivity is very hard to achieve. It needs some research and patience. If you want to do something honest, you have to explore it a little longer.