When Spike Lee spoke after an anniversary screening of Do the Right Thing in Atlanta, he made sure to point out that there were many African-American writers, directors, and producers who paved the way for him. Listening to Lee, I felt ashamed that I’d heard of but not seen the work of so many of the people that he mentioned. I decided to devote a week to African-American cinema to coincide with Black History Month. In a week I have only scratched the surface, but it’s been a great way to delve into an area of movie history that I previously knew very little about.

The Films

The Murder of Fred Hampton (1971) dir. Howard Alk

Beat Street (1984) dir. Stan Lathan

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) dir. Melvin Van Peebles

Within Our Gates (1920) dir. Oscar Micheaux

Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist (1979) dir. Saul J. Turell

The Emperor Jones (1933) dir. Dudley Murphy

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973) dir. Ivan Dixon

Hollywood Shuffle (1987) dir. Robert Townsend

The Murder of Fred Hampton

Howard Alk’s documentary is about more than the murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton, it’s also about Hampton’s life and about the charisma that made him a target of racist reactionaries. Hampton’s speeches and conversations captured in the film are incindiary but they are reasoned and literate. His call to take up arms against the pigs is balanced by his absolute insistence that people be educated about the reasons they should join the Black Panther Party. Over and over again he references the proletarian struggle and socialist ideology as ways to combat the racist oppression that he sees as a function of capitalism and he makes a compelling if heated argument. The film itself works to build Hampton up as a leader and a target before it spends the last half hour disecting the discrepancies between the official account of the police raid in which Hampton was killed and the forensic evidence that suggests gaping holes in the official story. It’s heartbreaking to know that a well-spoken but incindiary leader of the Black Panthers was assassinated by a racist and paranoid government but that seems the only reasonable conclusion. A collection of newsreel footage that is used in the film can be viewed at archive.org.

Beat Street

I get the feeling that Beat Street has suffered from an association with the more popular but less serious Breakin’ movies. Beat Street tackles so many social, cultural, and artistic topics effectively that I could spend a whole column on it. Stan Lathan got his start directing TV, notably Sesame Street, before directing The Cotton Club in 1982 and Beat Street in ’84. Here he manages to interweave the stories of a handful of friends who represent the pillars of hip hop culture: Lee is the breakdancer, Kenny is the DJ and MC, and Ramon is the graffiti artist. In fact, all of those aspects of hip hop are introduced in the film’s very first scene–a clever way to set up the film’s scene and scope. Lee and the rest of the Beat Street breakers are amazingly fun to watch, Ramon’s story as a struggling young father balancing his art and his responsibilities is the film’s heart, and Kenny’s demonstration of his musical collage using turntables and cassette decks is inspired. Beat Street isn’t just a showcase for breakdancing and rap parties–it’s a film about the time and place that gave birth to fertile new art forms, and it’s a touching story about a handful of people who grew up in the middle of it. I’ve seen this movie a dozen times and I know every note of the soundtrack by heart but I’m happy to say that watching it now, more than 25 years after the first time I saw it, I’m finding even more to love about it.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

I wasn’t sure that I was going to make it past the opening scene of Melvin Van Peeble’s film that helped to kickstart a whole movement in the 1970s. The scene where Sweetback (an orphan being raised by doting prostitutes) got his name was one of the most wrong things I’ve ever seen in a movie. After that, it was hard to find anything about the movie shocking, but it’s easy to understand the allure. Sweetback doesn’t say more than about six or seven words in the whole film–his role in life is to be a sex performer. When cued, he drops his pants and lies down on whichever woman is spreading for him and that’s that. They all seem to enjoy it while he is a blank page. Sweetback is a man of reluctant action, dragged into seedy dealings with crooked white cops and then forced to run for his life when he becomes their next target. Certainly more important than the plot or the characters is Sweet Sweetback’s place in history as an independently financed and produced feature for a black audience. The film’s commercial success helped to pave the way for a wave of Blaxploitation as studios saw an easy dollar in cheap thrills and a built-in audience. Van Peebles’ film is remarkably weird and psychadelic, a little shabby around the egdes, almost experimental at time, but notable as the cinematic expression of a voice that had previously gone unheard.

Within Our Gates

This film from pioneer Oscar Micheaux is reported to be the oldest feature film by made by an African-American director still in existence today. You can watch the whole thing (as I did) on archive.org for free. Within Our Gates is a complicated melodrama that deals bluntly with race relations in the early part of the 20th century. Though perhaps not as stylistic and technically accomplished as some of his contemporaries working in the silent era, Micheaux was nevertheless a trailblazer. He had already been a successful entrepreneur and writer before he began producing and directing films in 1918. His production company turned out features based on his writing and he went on to write, direct, and produce dozens of films between 1918 and 1948. The themes that drive Within Our Gates are the same as those that continued to propel independent African-American cinema into the 70s. Like Sweetback, the protagonists of Within Our Gates are mistreated, misjudged, and held back at nearly every turn by whites. But Micheaux’s view of race is nuanced. Not all of the black characters are beyond reproach and not all of the white characters are purely evil (though they all are clueless.) The film’s crude construction made it difficult to really enjoy, but I was struck by the story behind the production–a story of a black man taking the means of production and distribution into his own hands so that he could share his voice with the world. It’s a story that has been repeated a number of times since.

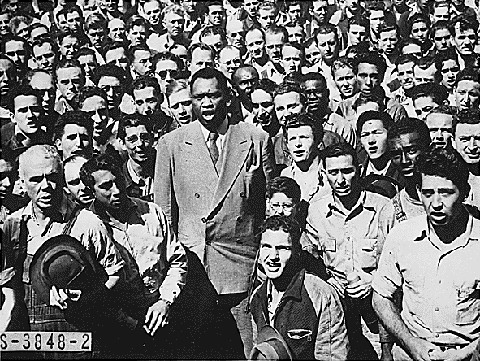

Paul Robeson

When I was 13 I saw a one-man play about the life of Paul Robeson and I was mesmerized. I went back to watch that play three times before it closed and each time I couldn’t believe that someone as dynamic and interesting as Paul Robeson had really walked the earth. Athlete, singer, actor, activist–was there anything he didn’t do and do exceptionally well? For years after I saw that play I always smiled when I heard Robeson’s name but somehow I never sought out any of his work. Criterion put out a beautiful boxed set celebrating his life and his films which gave me an opportunity to catch up in some small way. The Emperor Jones was Robeson’s first major film role and it’s easy to understand how it made him a star. He is a commanding presence in every frame of the movie, and though he’s playing a hustler and generally wayward man, he’s still powerful and graceful and intimidating. The documentaries that accompany the feature on the “Icon” disc of the set put Robeson’s work into perspective. He was larger than life and his considerable film career is only a small chapter of the story that makes him fascinating.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door

If dark, stinging satire is what you’re after, you can’t do much better than this 1973 film about a man who works his way into the CIA only to leave a few years later to organize a nation-wide revolution. It’s one of those movies that starts off playing for laughs but that by the end has turned to the meaner-spirited side of satire. As revolution breaks out and small pockets of freedom fighters take their demands to the streets, the film almost wants to make you feel bad for laughing earlier. I was struck by how parallel this film’s narrative felt to the story of CIA-trained freedom fighters in various places around the world. We often wind up on the wrong side of those conflicts and the training and guns and structure we provide to guerrillas comes back to bite us as it does here.

Hollywood Shuffle

I don’t know how I made it this long without seeing Hollywood Shuffle. I mean, it’s not even something I’ve seen a part of on TV. Robert Townsend’s satirical look at the roles for black men in Hollywood follows his character Bobby as he tries to land an acting role other than a slave, waiter, pimp, or jive-talking hoodlum. The story detours off into Bobby’s daydreams and fantasies and these segments feel like short sketch-comedy skits that break up the real action. Some of them work better than others–the “Black Acting School” bit is a classic while Bobby’s dream job fantasy as a dective in a film noir goes on for far too long. Like most good comedies, Hollywood Shuffle throws a joke or witty insight at the screen every minute or so and some of those are bound to flop, but the film keeps trying and it continues to push the stereotype buttons until Townsend has made his point. I’d like to think that the situation has gotten somewhat better since 1987. The world may not have truly seen “Rambro” but we do have a (too-small) group of bankable black stars who anchor pictures and sell tickets across demographic segments. I’d love to see Townsend or one of his proteges revisit this idea now to see if the same satirical tone still holds up, or if the contemporary sitatuation in Hollywood demands something even more biting.

Other Movie Weeks in 2011

Vampire Week

Recent Westerns Week

Non-Godzilla Kaiju Week

Woody Allen Week

Secret Agent Week

Asian Action Week