Rental Store • Open-Source Film • The Black List

Rental Store • Open-Source Film • The Black List

In April of last year, I sat in the Trustees Theater in Savannah, GA practically vibrating with excitement because not only was I about to see Walter Murch speak, but I was sitting close enough behind him to take a dumb phone picture of the back of his head. While I had always been on the “director’s track” for my Film degree, my minor in sound design and extensive training with picture editing throughout the years meant that Murch was something of a patron saint and his appearance at our school so close to my graduation felt like particularly serendipitous timing. During his lecture he covered topics like editing theory, specific video codecs, his organizational process, his workspace, and he showed us a clip from his then latest project, Coppola’s Tetro. Lodged amidst all of that was a very brief tangent about 3D, and the inherent limitations of the format. As I sat, eager to ask my sound design question in the Q&A, I listened to Murch discuss the human eyes’ difficulty with separating their plane of focus from the point of convergence between their axis. Little did I know that just shy of a year later, Murch would provide this same explanation to a particularly cantankerous Roger Ebert via email, and that the brilliant critic would then use that little physiological factoid as the punctuation mark on what would by then have become his long-term, prosaic battle against the return of 3D to the cineplex. This would culminate with the typically level-headed Ebert posting a mind-bogglingly stubborn and ostrichian* blog with a title only a TV news pundit could love, “Why 3D doesn’t work and never will. Case closed.” Cue a wave of news sites running with that biology lesson and Ebert’s blog, and then a wave of rebuttal editorials, and of course all the thousands of opinionated reader comments attached to them (567 on Ebert’s original blog alone).

In April of last year, I sat in the Trustees Theater in Savannah, GA practically vibrating with excitement because not only was I about to see Walter Murch speak, but I was sitting close enough behind him to take a dumb phone picture of the back of his head. While I had always been on the “director’s track” for my Film degree, my minor in sound design and extensive training with picture editing throughout the years meant that Murch was something of a patron saint and his appearance at our school so close to my graduation felt like particularly serendipitous timing. During his lecture he covered topics like editing theory, specific video codecs, his organizational process, his workspace, and he showed us a clip from his then latest project, Coppola’s Tetro. Lodged amidst all of that was a very brief tangent about 3D, and the inherent limitations of the format. As I sat, eager to ask my sound design question in the Q&A, I listened to Murch discuss the human eyes’ difficulty with separating their plane of focus from the point of convergence between their axis. Little did I know that just shy of a year later, Murch would provide this same explanation to a particularly cantankerous Roger Ebert via email, and that the brilliant critic would then use that little physiological factoid as the punctuation mark on what would by then have become his long-term, prosaic battle against the return of 3D to the cineplex. This would culminate with the typically level-headed Ebert posting a mind-bogglingly stubborn and ostrichian* blog with a title only a TV news pundit could love, “Why 3D doesn’t work and never will. Case closed.” Cue a wave of news sites running with that biology lesson and Ebert’s blog, and then a wave of rebuttal editorials, and of course all the thousands of opinionated reader comments attached to them (567 on Ebert’s original blog alone).

As I watched all of this over the last few weeks till now, I’ve found myself simultaneously sympathetic and revolted by the various positions and opinions lobbed by the two sides of this ongoing dialogue. Level-headedness is always present of course, but it’s usually drowned out by easily endorsed or dismissed hard-line opinions. As it has with politics proper, the noisy feedback loop of hyperspeed communication in which we live, learn, and converse has applied its centrifugal force on the discussion and turned most everyone into evangelicals for one or the other side. The ultimate irony is achieved as 3D is turned into an easily digestible, easily argued, and falsely binary issue… that is to say, the argument over 3D has become markedly 2D. Pick: 3D fucking goddamn sucks and it’s a fad, or 3D is awesome/growing and it’s here to stay.

My own opinion has varied wildly, changing with each poor post-conversion, exciting new technological achievement, dumb studio 3D remake announcement, or exciting filmmaker that’s decided to take on the format. Ultimately, when Nolan announced that The Dark Knight Rises would remain two-dimensional, I took it as an opportunity to “declare” a guardedly optimistic stance on the format overall. Since then though, I’ve noticed things that have made me consider the possibility that yes, this new wave of 3D could very well recede and become a marginalized footnote. This sparked a weeks-long search through as much material about 3D as I could find, with the hope that I could get a better grasp on where the format stands technically, artistically, and culturally. As you can tell from the title of the piece, I’m sticking with my conclusion that 3D is here to stay. That comes with a lot of caveats, largely because the life of 3D is no longer just tied to whatever in-your-face remake is in theaters this friday.

The State of 3D… in 3D!

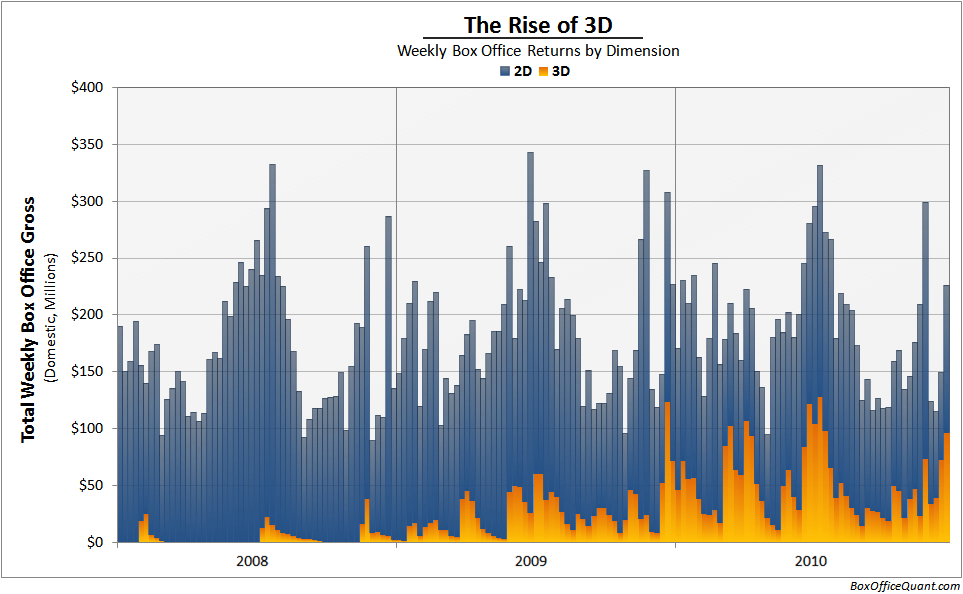

I think we can all agree that 3D has, at the very least, managed “fad” status– meaning it’s legitimately captured the zeitgeist and is the talk of the town, so to speak. This is self-evident, even if the sustainability of the trend is not. To figure out if this is a fad that will translate into a long-term paradigm shift in the way we interact with and consume media, we can only look at what’s going on now and try decipher if that is simply the excitement of novelty, or the fulfillment of genuine demand (be it newly created or long-standing). Naturally our starting point is going to be the movie theaters, where dozens of major releases over the last two years have ramped up the conversation about 3D, with Avatar being the nexus of the conversation. While 3D films have been stepping out of the IMAX and boutique theaters since 2004, it wasn’t until 2008 or so that the steady stream really began, all leading up to James Cameron’s long-promised statement about the future of cinema which, whether it convinced you or not, has still remained the point of comparison. The staggering box office success and undeniably sophisticated presentation of Avatar is still clearly unmatched, despite the film’s multitude of shortcomings. Studios immediately scrambled to jack up their 3D film output, which led to the bubble of post-conversions that is just now starting to burst as more natively-shot 3D films emerge. While we are inevitably leading towards a wave of post-converted rereleases of classic films (George Lucas leading the way), the rushed glut of hack-job post-conversions will be a footnote in the history of 3D, whether the format in general sticks around or not.

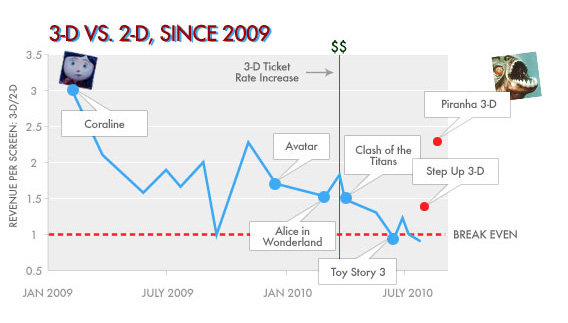

So here we are at the front end of 2011, with something like 2 or 3 dozen notable 3D releases expected in the next year, and as many more in 2012. Massive franchise reboots and follow ups like Spider-Man, The Hobbit, Transformers 3, and Pirates 4 shot, are shooting, or will shoot in native 3D. The question now is if the delayed-cycle of the studios means we’re only now going to be getting proper 3D once it’s too late, after the shine has already worn off. Slate recently ran an in-depth piece concluding that 3D returns have already diminished relative to 2D distribution, to the point where there is little or no extra profit involved. This is a tough thing to call though, as studios famously wrap up their real number in heaps of accounting bullshit, and so Slate is forced to draw its conclusions based on per-screen averages, a figure that’s being constantly diluted for 3D films as more and more screens are equipped to project 3D movies. So Slate‘s conclusion that audience interest has diminished and that “the added benefit of screening in three dimensions is trending towards zero” is ultimately based on a very fluid metric that could easily be spun towards calling 3D a great success…

It’s just as easy to look at the numbers for 3D and see a maturing market that has reached the point where it becomes sustainable and part of a long-term business model. Our friend Edmund at the new site Box Office Quant draws a different conclusion from Slate when looking at the trends of the 3D market in the last few years. Drawing from his background in Economics, Edmund took a bigger picture look at the returns of the third dimension and while similarly concluding that the market has indeed become saturated, the fact remains that 20.2% of US box office returns in 2010 came from 3D films (and that’s with the 2D showings of those films factored out, meaning that 20% is pure 3D money). With only 3% (at most) of returns coming from 3D films before 2008, those numbers represent a healthy expansion no matter how you slice it.

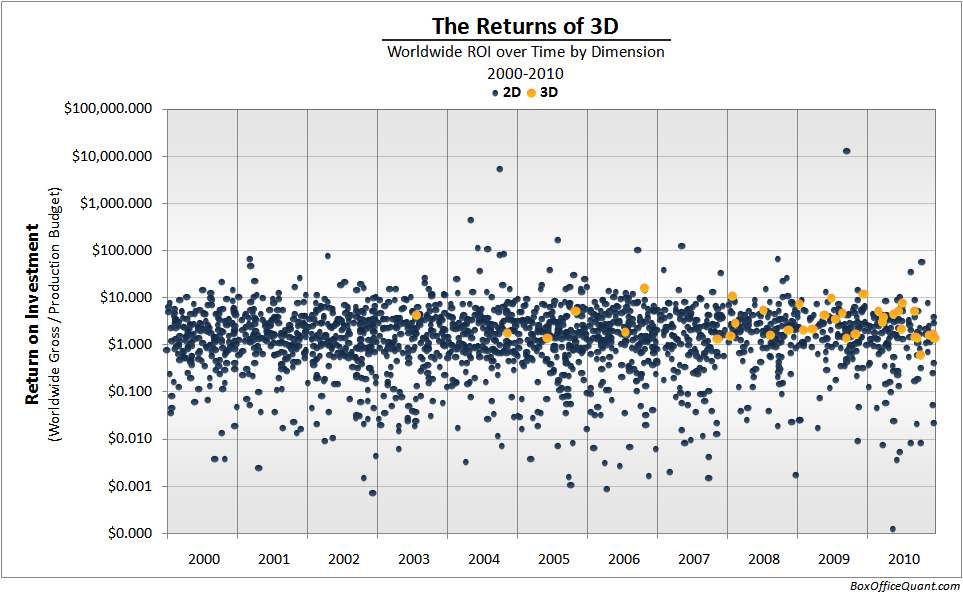

BOQ pushes it even further by comparing the overall worldwide return-on-investment of 3D films, and finding that they have remained consistent and profitable, with a dollar spent on a 3D film returning $3.69, versus the $2.51 return from a dollar spent on a 2D film. Of course, it’s important to note that 3D films are not an average cross-sampling of released films- the studios don’t tend to put the effort into a 3D release of a film they’re not at least semi-sure about, but it remains clear that 3D has earned its keep thus far, and remained remarkably consistent when viewed with a wide lens. We’re in a tumultuous time with a shitty economy, and yet a “premium experience” format has managed to break even or better, all the while providing studios with the ancillary benefits of one more complication for pirates, another excuse to double-dip in the home market, a new gimmick to plaster on posters, and another means by which they can differentiate the movie theater and home theater experience. This explains why the largest chain of movie theaters in the county has doubled its order for 3D screens from RealD, which have them contractually set for nearly half of their screens to be 3D ready. This order happened within the last month, after the accountants had plenty of time to process the receipts of 2010 and draw their conclusions about the continuing future of 3D. An order like that is not a conservative measure from a company hedging their bets, it’s a strong vote of confidence that audiences will continue to come.

The fact that the “fad” has pretty much rode the wave past the post-conversions and into the home-stretch of better-quality, natively-shot 3D suggests the odds are in favor of the format sticking around. I think Devin Faraci had a point when, a little over a year ago, he wrote a death knell for 3D based on the studios foolish decision to rush in and choke the growth and kill the novelty with pop-up book 3D. Warner Brothers decision to forgo a 3D release for Harry Potter 7 made it clear that the backlash on poorly-converted films like Clash of the Titans was heard loud and clear (even if the protest never amounted to lower receipts!). The studios seem to have lucked out though, and no major financial 3D failures have gutted the momentum of the “premium experience” and while we can declare the “shine” is off 3D all we want, tickets are continuing to sell. I don’t believe for a second that it will be Pirates 4, or Cars 2, or Transformers 3, or Kung Fu Panda 2, or Happy Feet 2 that suddenly pulls the wind from 3D’s sails- do you? The market has made it past the thin times and is about to hit a sweet spot that’s only going to make the books look better for the big guys.

3D Works And Will Always Work. Case Closed

If the economics provide only, at best, shaky and insubstantial ground on which to declare the end of the 3D wave imminent, then how about good ole physics and biology? That’s the tack Ebert used to “close the case” on 3D in the editorial I mentioned above, based on Walter Murch’s optometry lesson. If you still haven’t gotten a grasp on exactly what Murch is talking about, I’ll break it down quickly. Essentially the point is that the human vision relies on a number of basic biological and psychological function to operate. Two of those functions specifically relate to our perception of depth, and thus come into play when discussing cineplex 3D- accommodation and stereopsis. Accommodation is the ability of the eye to shift its focus plane nearer and farther away from itself- for the film enthusiasts in the room, it’s the eye’s ability to rack-focus. Stereopsis is our eyes ability to perceive depth by reconciling the minor differences in the two images provided by our eyes as they converge on the same object.

What Murch is saying (and what’s a well known fact among filmmakers and engineers working with stereoscopy) is that when we watch a 3D film our eyes are forced to separate those functions. Instead of our eyes converging on the same point around which our eye is currently focusing, our eyes are forced to focus on the plane of the screen (the flat source of the photons bouncing into our eyes) while they physically converge behind or in front of that screen-plane to look at the subject of the image. Murch naturally acknowledges that we are certainly capable of this function, otherwise no 3D film would have ever worked, but that it is a new demand on our brains is akin to “tapping your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time” and that it demands of our eyes “something that 600 million years of evolution never prepared them for.” This explanation is what provided the basis for Ebert’s equivelent to sticking his fingers in his ears and yelling “LA LA LA I CAN’T HEAR YOU 3D!”**

Again, as noted above, this launched a thousand blogs about what this meant for 3D, including rebuttals from more 3D-appreciative opponents that respectfully disagreed. Todd Gilchrist provided one such well-reasoned rebuttal for Box Office Magazine where he explained why Murch, despite his technical bona fides, is a little off on his explanation of our eyes’s interaction with 3D projected images…

Again, as noted above, this launched a thousand blogs about what this meant for 3D, including rebuttals from more 3D-appreciative opponents that respectfully disagreed. Todd Gilchrist provided one such well-reasoned rebuttal for Box Office Magazine where he explained why Murch, despite his technical bona fides, is a little off on his explanation of our eyes’s interaction with 3D projected images…

“…But the exact reason that 3D works is not simply because it projects the appearance of multidimensionality on a flat plane, but because our minds recognize the depths of those images and we no longer see the plane—at all. As such, we are not re-evaluating multiple depths of focus according to the fixed distance of the screen, but reacting spatially to objects in the frame in exactly the same way we do if we saw them in real life.”

Todd’s point is that the screen plane disappears, and we are reacting to a depth-filled image as we naturally would. Interestingly enough, this was very close to the answer I received from Andrew Wight, producer of the recent 3D release Sanctum, when I explained Murch and Ebert’s specific technical complaint. Andrew Wight has extremely serious experience with shooting in 3D, having, as his studio-provided bio states, “worked very closely with James Cameron and Vince Pace in the development of production techniques utilizing the Cameron/Pace 3D camera system, and has been forefront in navigating the post-production pathway for making large-format 3D films.” It was extremely fortuitous timing that I was able to interview Mr. Wight mere days after Ebert’s article, and get an answer from someone who should know. His response-

“The problem is, even what you just said there, “the screen plane” – there is no screen plane. 3D is a way of projecting images so that people can see the world the way that we normally see it, and that is- you don’t have any perception of where the screen is relative to you. If the lens of the camera is three feet from the subject, the optical illusion in the theater is that the subject is three feet from the end of your nose. How do you do that? Well, you’ve got to help people out a little bit, because there are optical disparities caused by what you can photograph with two cameras. [The camera’s don’t] have a brain to recompose that image, you have to help the people in the audience. You do that by putting the pictures on these screen already converged so their eyes don’t have to do the work”

From these rebuttals it would seem that Murch and his experience on Captain Eo have left him with some misconceptions about how stereoscopic project works. Except, the thing is, if Gilchrist and Wight were correct, they would be talking about holographic project or some other technology, because Murch is absolutely correct.

What these explanations do is make 3D sound like a technology that is creating a genuine construct of light that recreates objects in front of you in the theater, and this is simply not the case. Stereoscopic projection is an optical illusion that does result from a flat, 2D dimensional picture that through visual trickery gives your brain the impression of depth. True depth does not exist in the auditorium you’re watching the film in (obviously- try taking off the glasses), and our eyes are not focusing independent of the screen plane. The depth of field in a 3D film frame is determined on-set by the camera’s lens, but in the theater your eyes must be focused on the plane of the screen, otherwise your brain would never have the opportunity to properly reconcile the left and right images and create the illusion. The idea that your eyes are converging and focusing on any old thing in the movie frame is incorrect, and would only accurately describe viewing a true holographic image, where the light was creating a volumetric “object” for our eyes to look at. If you require a little more scientific background (or just plain proof) that this is the case, I would point you towards this extremely technically-specific paper entitled “Image Distortions in Stereoscopic Video Systems” generated by Andrew Woods and his colleagues at the Curtin University of Technology (the source of the distortion grid image above). This paper (from 1993!) goes in-depth about field-sequential stereoscopic projecting and its relationship with actually shooting the images. There is a lot to learn about the kinds of distortion 3D filmmakers must contend with in their systems, which makes Wight and Cameron’s achievements all the more impressive. However,it also contains a segment about the “human factors” of the display process, which includes this bit-

What these explanations do is make 3D sound like a technology that is creating a genuine construct of light that recreates objects in front of you in the theater, and this is simply not the case. Stereoscopic projection is an optical illusion that does result from a flat, 2D dimensional picture that through visual trickery gives your brain the impression of depth. True depth does not exist in the auditorium you’re watching the film in (obviously- try taking off the glasses), and our eyes are not focusing independent of the screen plane. The depth of field in a 3D film frame is determined on-set by the camera’s lens, but in the theater your eyes must be focused on the plane of the screen, otherwise your brain would never have the opportunity to properly reconcile the left and right images and create the illusion. The idea that your eyes are converging and focusing on any old thing in the movie frame is incorrect, and would only accurately describe viewing a true holographic image, where the light was creating a volumetric “object” for our eyes to look at. If you require a little more scientific background (or just plain proof) that this is the case, I would point you towards this extremely technically-specific paper entitled “Image Distortions in Stereoscopic Video Systems” generated by Andrew Woods and his colleagues at the Curtin University of Technology (the source of the distortion grid image above). This paper (from 1993!) goes in-depth about field-sequential stereoscopic projecting and its relationship with actually shooting the images. There is a lot to learn about the kinds of distortion 3D filmmakers must contend with in their systems, which makes Wight and Cameron’s achievements all the more impressive. However,it also contains a segment about the “human factors” of the display process, which includes this bit-

“A widely discussed limitation of field-sequential stereoscopic displays is the association between accommodation and vergence. In real world viewing,vergence and accommodation are normally closely linked visual actions, whereas stereoscopic displays require a different visual action. The eyes must remain focused at the surface of the screen at all times regardless of where the eyes are verged in the stereo monitor.”

Now I don’t think Gilchrist or Wight are or were trying to lie to anyone, or even act as propagandists. Todd is one of the most upstanding gentlemen I’ve met in the online film world and he definitely knows his shit. Andrew Wight was nothing but kind and reasonable in the time I spoke with him, and definitely knows his shit. What I believe is that they were trying to address a concern some overly-negative 3D critics have spun as apocalyptic for 3D, but doing so with an explanation that dodges the actual principle of optic physics that’s being questioned. It’s an attempt to combat histrionic criticism by presenting an easier to understand answer, it just happens to misrepresent the physics a little. The fact remains though, that Mr. Murch and by extension Mr. Ebert are right. But, what does satisfactorily deny Ebert’s claim that 3D can’t and never will be a comfortable experience is something that Wight and Gilchrist both raise, and that Murch acknowledges himself- the self-evident fact that 3D works anyway. That is to say; yes, 3D asks our eyes to do something that is new and mostly unprecedented, but that doesn’t matter.

It’s been said by others before, but is worth repeating- our brains were never intended to reconcile 24 frames flashed at 48 or 72hz in a dark environment to create the illusion of fluid motion. Picture editing, rack focusing, and camera movement are all based on the same optic tricks our eyes use (blinking, accommodation, and head movement) but our eyes don’t have a frame rate, nor do our ears have a sampling rate. This is in addition to the dozens of things that we ask our minds and bodies to do on a daily basis that have no biological precedent, whether its operate a motor vehicle or sit in office chairs while staring at a screen for 8 hours. Yeah, there are side-effects, but that’s never stopped us and it never will.

The other upside? We get better at watching 3D. The same study I cited above makes mention of viewers of stereo material improving their ability to perceive the depth, and that findings in the study were consistent with that. I’m sure most of my colleagues would agree that being forced to see nearly every 3D films that’s released has made most of us more comfortable seeing the films, even when the conversions suck. And before one dismisses the format because it may require visual training for some, consider our increasing ability over the last century to reconcile faster and faster picture editing. We’ve grown more accustomed to perceiving imagery from extremely fleeting shots, and while even that trend may annoy you, it’s another growth in film grammar that has given the interesting filmmakers a truly awesome tool in the toolbox.

To be sure, there are new limiting rules created by this format that filmmakers will be constrained by for at least the time being. This was for true for the first “talkie” filmmakers who found themselves constrained by cameras that had to remain in giant soundproof boxes. 3D Filmmakers must now be cognizant of cutting from shots of extreme depth to shots of closer images, because our eyes need time to adjust their convergence (about 350 milliseconds to go from infinity to 7cm from the eye). That’s not dissimilar from the long-established “180˚ rule” which advises against cutting across the established axis of a scene in two-dimensional filmmaking. That rule is often stretched or outright broken because we’ve become used to more jarring cuts over time, and for artistic reasons. The same may soon be true for current 3D filmmaking rules- in fact, I’d bet on it. This is a process that will continue as long as we’re refining the technology of filmmaking, and the improvements beyond 3D are already clear. IMAX is only doing better and better (and bigger and bigger), while Ebert himself has praised a format called Maxivision that is a form of the high-frame rate projection that James Cameron hopes to implement with the sequel to Avatar.

There is no end to the changes in technology, no finish line we’re trying to cross- like evolution in nature there are only mutations that lead to refinement. We try desperately to predict the outcome of particular experiments and fads based on history, but cinema is still so young that these comparisons are deceiving. What’s amusing is that those who compare 3D to the development of sound or color in cinema and those who reject the metaphor are often both wrong for different reasons. The comparison doesn’t really stick because of how tied to the very birth of cinema sound and color were. Film technologies never had much of a chance to standardize before color and sound became part of the landscape, and there is so much historical and political context to the changeovers that are unique to that time period that it’s not particularly useful to force a comparison with today’s trend. That said, most who reject that comparison do so because they claim sound and color were more natural elements for filmmaking to absorb. The problem with that idea is that film sound (and often film color) have a very tenuous relationship with reality at best.

This is especially true for a motion picture soundtrack, which is a sculpted and extremely subjective piece of artifice that is far more manipulative and unreal than anything you could put on the screen. If you want sound that approximates how we hear the world, imagine listening to The Godfather if its audio was presented binaurally (example – close your eyes and use headphones). That’s a whole new realm that makes mixing, effects, and foley creation a very different matter. The same is true with color to an extent- color correction often creates images that are far too full of contrast and heightened color schemes to genuinely resemble what we see on a day-to-day basis. It’s all artifice my friends, and 3D is no more unnatural than the rest of it, all things being equal.

If you want a better comparison for the 3D wave, I would point to something much closer to us- digital HD. New format that upgrades an old format? Check. Requires much more powerful equipment and entirely new workflows? Check. Extremely showy, obvious difference between the new and the old? Check. Politicized, with well-reasoned folks on both sides? Check. Lightspeed penetration into the consumer marketplace? Check. The list goes on… While five years ago you had most old-school filmmakers clinging to film stock and decrying the limits of digital, now Roger Deakins doesn’t know if he’ll ever go back to film. How much faster have great filmmakers started testing out 3D compared to digital? There’s no way it’s disappearing that quickly.

The Best Is Yet To Come

Atmospheric Perspective - These mountains are 2D, even in real life. Faces are where 3D is at...

What is so immensely frustrating about the critics of 3D (who have a de facto figurehead in Ebert, but are composed of a wide swath of not-dumb people), is the refusal to look past the studio cash-grabbing, as disgusting as it may be, and see that the technology is progressing right now, and that interesting filmmakers are toying with the format right now. We don’t have to wait or suffer through a decade of nonsense, it’s happening every day. Martin Scorsese is giving the format a shot, James Cameron is still dedicated to doing cool things, Werner Herzog is taking 3D to places humans haven’t been in 10,000 years, and a whole bevy of auteurs are coming around to the idea of shooting everything from epic blockbusters to period dramas in the format. It’s inevitable that we’ll get a 3D film that is based around character and story rather than spectacle, and perhaps it’s then critics will come around to the potential. The irony is that dramatic, human-level imagery is what’s best suited for 3D! Science is definitely on the sides of the 3D close-up, as human beings start losing the ability to perceive depth after only a few dozen feet, and by the time you’re looking at gorgeous vistas and farway mountains, you’re looking at objects that have been flattened by atmospheric perspective (the phenomenon of diminishing contrast and detail in a faraway object, due to the atmosphere in-between subject and viewer).

I’m extremely frustrated by the idea of losing the choice between 2D and 3D, and I’m even more frustrated by cynical studio exploitation that will inevitably come with it. Like the development of CGI though, I’m very willing to sift through the bullshit to see what visionary filmmakers, who are willing to wrap their minds around the unique challenges of the format, are capable of doing. CHUD-favorite Guillermo Del Toro is always cited as a master at employing CGI only where necessary, and in a sophisticated way that produces images that would have otherwise been impossible. Imagine that same mind geared towards the use of depth in a frame of film. CHUD’s own Iain Stasukevitch had a great conversation with 3eality Digital CEO Sandy Climen where they reached the same conclusion. Like them, I can’t wait to see what happens.

Like many filmmaking technologies our ability to capture data and imagery has indeed outpaced our ability to satisfactorily exhibit it, and there are hurdles to 3D projection with which we must be patient. Brightness levels remain an issue, but it’s inevitable that the lost stop of luminosity will be recovered soon- be it brighter prints, less opaque glasses or another solution. As for the damn glasses? We’ll only have to be so patient since there are glassless displays in TVs, videogames, and cellphones today. We don’t have to wait five years for the tech companies to start clumsily trying out more progressive 3D products- they’ve out there today. This is the added benefit of 3D capturing the popular cultural zeitgeist- it has become an obsessive focus in all tech fields, and everyone is jumping on the bandwagon. Apple, along with every major technology company, have their own patents based on 3D techniques, and eventually the marketplace will start filling with better and better implementation of the technique. In only a few weeks Sony will release a $250 3D Flip-style camcorder, and similar products will soon follow at every price range. Devices like this will mean that whenever and wherever the next revolution occurs in the world, we’ll be getting stereoscopic images back along with the tweets. That’s the biggest advantage this wave of 3D will have, in terms of staying relevant, is that is has latched onto our culture and is not just a gimmick of Hollywood. Sure, it filters out fastest through all of the dumb cultural detritus like 3D shoes, but we are genuinely enamored with the idea of 3D, and it’s quickly penetrating into every aspect of our media lives. Cheaper and cheaper technology means we have grown unaccustomed to letting Hollywood have all the fun, so don’t expect it to disappear just as we get our hands on it!

Like many filmmaking technologies our ability to capture data and imagery has indeed outpaced our ability to satisfactorily exhibit it, and there are hurdles to 3D projection with which we must be patient. Brightness levels remain an issue, but it’s inevitable that the lost stop of luminosity will be recovered soon- be it brighter prints, less opaque glasses or another solution. As for the damn glasses? We’ll only have to be so patient since there are glassless displays in TVs, videogames, and cellphones today. We don’t have to wait five years for the tech companies to start clumsily trying out more progressive 3D products- they’ve out there today. This is the added benefit of 3D capturing the popular cultural zeitgeist- it has become an obsessive focus in all tech fields, and everyone is jumping on the bandwagon. Apple, along with every major technology company, have their own patents based on 3D techniques, and eventually the marketplace will start filling with better and better implementation of the technique. In only a few weeks Sony will release a $250 3D Flip-style camcorder, and similar products will soon follow at every price range. Devices like this will mean that whenever and wherever the next revolution occurs in the world, we’ll be getting stereoscopic images back along with the tweets. That’s the biggest advantage this wave of 3D will have, in terms of staying relevant, is that is has latched onto our culture and is not just a gimmick of Hollywood. Sure, it filters out fastest through all of the dumb cultural detritus like 3D shoes, but we are genuinely enamored with the idea of 3D, and it’s quickly penetrating into every aspect of our media lives. Cheaper and cheaper technology means we have grown unaccustomed to letting Hollywood have all the fun, so don’t expect it to disappear just as we get our hands on it!

As for Friday night at the movies? Well, 3D is not the conclusion of cinema, but as it reaches a point of sophistication and comfort, it could become the next standard. I think we are currently on the path towards that future, which is admittedly an uncomfortable thought. What is most likely to happen is that technologies will fragment, and like the 20 year transition from mostly-black and white to mostly-color, you’re gonna see a lot of movies shot and projected in different ways over the next decade or two. It will be as it has always been though- the work of artists who approach their ideas with care and careful consideration will exploit whatever medium they choose to use in wonderful ways, and we will appreciate them within those contexts. 3D has arrived and will remain one of those choices. Celebrate it, deal with it- whatever you choose, I wouldn’t bother denying it any longer.

Thanks for reading this enormous stack of words! I really want to hear your thoughts on this controversial topic, so hold nothing back in the comments below, or join the conversation on the message board.

Finally, if you dig this piece, please “like” it, share it on your facebook page, tweet it, or all of the above!

————————-

* This is a word I have just now made up…

Ostritchian (adj.)

[aw-strich-ee-uhn]

1. of or pertaining to Ostriches;

2. prone to burying one’s head in the sand;

3. stubbornly clinging to an argument with no acknowledgement of nuance, and doing so in the most childish, narrow-minded way possiblebertwhatthefuckmanyou’rebetterthanthis

————————-

** Pardon the metaphor… no disrespect intended towards his recent condition.