Every single person who visits this site fancies themselves a film fan. From the nameless readers who don’t interact to the regular Chewers on the Boards to every single person on the staff – we love film. We live for it. We watch as much of it as we can. But, sadly, we’ll never be able to see everything. We’ve missed a lot over the years and sometimes we’ll miss one of the big ones. One of the classics or cult favorites that has had everyone talking and proclaiming their love for years. That’s what this column is all about – the big ones that we‘ve missed. Every week a different member of the CHUD Crew is gonna play their own little game of catch-up and tell you about it here. Maybe it’ll get you to rewatch an old favorite you haven’t seen in years, maybe it’ll get you to catch up on your own list of shamefully neglected films. Either way, we hope you enjoy it.

.

At this point in my life, I rarely feel late to movie “parties.” There are of course heaps of amazing films that I have not yet seen, but that is almost always because they are either a) a “classic” more so in the sense that they are old and good but not must-see-great, or b) because I simply have not heard of them. And once a praised title hits my ears, that bitch is gettin’ its ass seen, usually within a month.

As for the true classics: high school is when I first became fully aware of the canon of films a buff needs to see, and over the years I systematically went down that list and devoured them all. Well, almost all of them. Through some confluence of fate, laziness, and presumably dark supernatural forces far beyond my control, there was always one film that went routinely unwatched even though 60 years of film historians and film fans were telling me it was one of the few truly must see films ever made. Hell, even ironically detached funnyman Mel Brooks sited it as his favorite film. I am talking about…

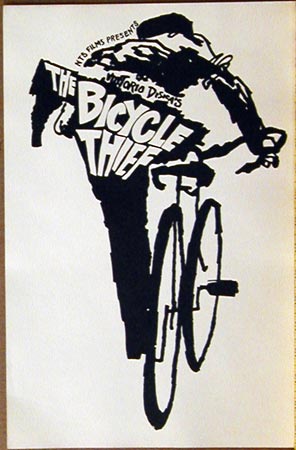

In recent years the American film world has started calling The Bicycle Thief by its literal Italian translation, Bicycle Thieves. While this correction towards accuracy makes perfect sense to me, I not only prefer the sound of the US release title, but I think it is more thematically thought provoking in regards to the events of the film. So bear with me, as I continue calling it The Bicycle Thief.

The Bicycle Thief (1948), director Vittorio De Sica’s adaptation of the novel by Luigi Bartolini, is a deceptively simple film. Set during the economic depression of post-WWII Italy, the film tells the harrowing tale of Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), an unemployed laborer. In the film’s opening scene, Ricci lucks into a new job posting advertisements around the city. But for the job he needs a bicycle. Which he doesn’t have. In order to purchase a bicycle, his wife sells off their last valuable possession, some nice bedsheets that were part of her dowry. Then, on Ricci’s first day, misfortune strikes when his bicycle is stolen by some lowlifes. Now, joined by his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola), Ricci futilely scours the city looking for the metal and gears he needs to feed his family.

The Bicycle Thief is in the top ten of the British Film Institutes’ “50 Films You Should See By the Age of 14” (entire list here), and I really wish I had seen this film when I was younger. The problem with being late to a real party is you often show up once everyone is obnoxiously drunk and all the good booze is gone. Showing up late to a movie “party” can be just as unfortunate – you often risk hype bias, inflated expectations, and/or impact dilution from having seen said film’s imitators and disciples first. I thought Thief was amazing, but that appreciation is coming more from a mental perspective, viewing the craft and storytelling prowess. But this film would have utterly destroyed me emotionally if I’d seen it in high school. It would have likely been a seminal film viewing experience, leaving me frustrated, sad, and angry – as Di Sica and Bartolini surely wanted. I think the BFI is fucking dead on. Certain older artwork needs to come at a particular developmental stage in your life to be maximally effective. I would compare it to listening to The Beatles. If I had never heard The Beatles until right now, I would no doubt dig the shit out of them, impressed by their songwriting abilities and catchy tunes. But having already heard the generations of musicians they inspired, The Beatles would not truly connect with me emotionally like they did when I was a kid (when they served as my gateway drug into the larger world of rock). Thus, for me, The Bicycle Thief is a cautionary tale of what can happen when you put off exposing yourself to amazing films for too long. Be warned younger CHUD readers!

That said, the power of the film was certainly not lost on me.

It kind of amazes me that I never saw Thief in film school, especially considering that I was shown several other neorealist films, though all from Germany. Neorealism, for those who don’t know, was a film style popular in war-torn post-WWII Europe that focused on the poor and generally used real locations and amateur actors to gain a vibe of authenticity and naturalism. Italy dominated the style, and Thief is the flagship of Italian neorealist films. But the professor I had who taught about neorealism had a real boner for German cinema. So here we are.

It feels awkward to wax on the virtues of a film that once placed #1 on Sight & Sound‘s greatest films ever made list. I don’t think the film needs my praise. But in the interests of maybe saving some young soul out there from missing out of the full impact of this wonderful film, as happened to me, here we go…

I am a lover of complicated (even convoluted) twisty narrative. Memento. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Toy Story 2. Oldboy. Possibly this predilection is also what makes me such a sucker for truly simple stories, but that is what I marveled most at while watching Thief. There are no tricks here. No subtext buried beneath symbolism, as so many “serious” filmmakers do. This film wears its heart on its sleeve. No frills necessary.

The bicycle is a powerful white whale here, because it is so pathetic. This same story could easily be told about a man who needs a car for work, or even a horse, but lowering the vehicle down to a bicycle makes the film heartbreaking in its mere concept. Nothing says economic devastation like having a family’s livelihood rest on the presence of a fucking bike. The only way this story could feel more immediately desperate is if the film was called The Flip-Flop Thief.

I loved that there were no subplots. Ricci’s relationship with his wife was established as strong and happy, despite their economic status, to give the film context, but she leaves the film quickly. We have no side-characters to deal with either. And most importantly, I loved that there are no other problems “greater” than Ricci’s dilemma with the bicycle. Specifically, I think it is amazing that the bicycle isn’t used merely as a backdrop for a story about Ricci bonding with his son Bruno. The shitty Hollywood remake of The Bicycle Thief would have Ricci at odds with his son, and by the end realize that the bicycle isn’t that important after all. Fuck that. The bicycle is everything. And by placing the importance squarely on the bike, and keeping it there, Di Sica allows for plenty of father and son bonding anyway. But with the streamlined purpose of trying to find the motherfucking bike.

While Ricci’s naturalistic interactions with other citizens and authority figures are superb to watch (and often enragingly frustrating), the heart and soul of the picture is the relationship between Ricci and his son (also the inspiration for yesterday’s Quick List). Maggiorani and Staiola are both excellent, with Staiola managing to be adorable while never cloying. The film’s most heartbreaking moments come from Bruno’s reactions to witnessing his father laid low time again. I think the emotional highlight of the film comes in the scene where Ricci has decided to fuck all and leads his son into a middle-class restaurant, the kind they can never afford to eat in. The scene is simultaneously joyous and crushing, as Ricci’s entire motivation is kind of a “well, our lives are over now, we might as well live it up.” Continuing this double-bladed sword of emotions is the look on Bruno’s face as they order food, and his continuing eye-contact with a snobby kid his age eating with his family – the moment speaks to the fact that Bruno has never experienced such mundane “splendor.” Then one side of that double blade gets duller and duller as Ricci drinks wine and his temporary spirit of happiness erodes, the reality of his plight returning.

SPOILER ALERT

Most poignant of all, though, is the film’s ending, when Ricci finally reaches the bottom of the desperation barrel and attempts to pay it backward and steal someone else’s bicycle. And is promptly caught. I can’t think of another film where the protagonist escapes conflict during the climax because he is so pathetic that his antagonists decide to just let him go. All this, of course, reflected back on Ricci in Bruno’s teary eyes, who has just watched his father reduced to total shame, first as a thief and then as an unsuccessful thief. This is why I prefer The Bicycle Thief as a title. It becomes entirely ambiguous at the end of the film, and in fact seems to be referring to our hero.

END SPOILER

This is a great film; one of the Greats, with a capital “g.” It is also marvelously available on Netflix Instant. So if you haven’t seen it… don’t live like me. Make this a priority. And if you know a younger, burgeoning film buff, make them watch this. And destroy their fucking week. They will thank you for it.