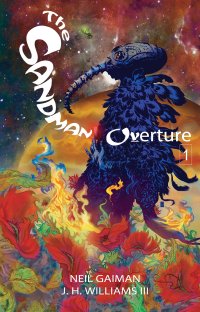

Sandman: Overture #1 (Vertigo, $4.99)

By Adam Prosser

Sandman was my gateway drug. Oh, I’d read comics before that, mostly Carl Barks stuff and Archie and so on (no superheroes, oddly enough) but they were just sort of there, part of the wallpaper of childhood. Sandman was the comic that made me sit up straight and realize you could do amazing things with this medium. It’s one of the few, possibly the only, comic to really take up the gauntlet that Alan Moore threw down with his work on Swamp Thing and Marvelman/Miracleman, building not just an epic narrative but an entire mythos from which stories could be constructed. Also like Moore’s work, it’s told in a series of “nodular” issues, each of which contains its own complete story with a beginning, middle and end (barring the occasional multi-parter), but also feeds into the larger story (and sometimes into a story within a story, or even a story within a story within a story…)

Every issue of Sandman felt dense, not in an intimidating way but in the sense that it felt bursting with ideas and potential. We live in an age where DC and Marvel tend to stretch every single story point out to miserly thinness, turning throwaway ideas from the 80s into the basis of multi-part sagas; to go back and read Sandman is to be reminded of a time when not only were comic writers not afraid to pack stories full of ideas, but to suggest whole narratives that were taking place offscreen. Indeed, a big part of what makes Sandman such a rich reading experience is that, unlike your standard superhero story, Gaiman was never afraid to leave huge gaps in the ongoing narrative, to create a sense that the stories had been accruing for millions of years before we ever started reading them, and that they continued offstage whenever we put them down.

Which brings us toSandman: Overture. We first met Morpheus, the lord of Dreams, as a tattered wreck pulled from the ether by a team of (somewhat cut-rate) magicians and kept prisoner for much of the 20th century. The only reason they were able to do so, given Morpheus’s godlike powers, was that he was apparently returning from an intense battle and had been seriously wounded. The nature of that battle was one of the mysterious gaps in the ongoing narrative of Sandman, and now, over 25 years since Gaiman started the saga, he’s finally returned to it to tell that story. Of course, right now, the focus is on vague portents of doom, the Sandman’s rebellious servant and proto-serial killer The Corinthian, mysterious goings-on across the universe, and a final, bizarre revelation that there may in fact be a lot more than one Lord of Dreams, something that “our” Morpheus seems to have been utterly unaware of.

The structure here is actually a lot closer to your standard superhero comic book than I generally expect from this series, almost as if Gaiman had to psyche himself back up to writing comics by passing through the familiar territory of Big Event Comics. It actually took me years to realize that Sandman is technically set within the DC Universe, making it a mythos within a mythos, but frankly, it always felt like an ill fit, and I think we can all be grateful that there was never an editorial edict that the events of Sandman had to fit within the larger DCU. In fact, I can’t help but wonder if Gaiman’s stepping up to make some kind of commentary on the New 52, or if, alarmingly, this is a ploy by the current DC leadership to fold Morpheus into their “rebooted” universe the way they did with Constantine and the other Vertigo characters. You’d think Sandman would be untouchable, but this is DC, the company that never saw a Golden Goose it couldn’t hack to death, and which is currently being run by a guy who claimed Sleepwalker was going to be “Sandman done right.” I’ll just let you ponder that statement for a while.

Enough of such dreary thoughts, let’s take a moment to reflect on J. H. WIlliams. When I heard he was going to be drawing this series, my first thought was, “Great, J. H. Williams returning to Sandman!” The fact that J. H. Williams had never actually drawn Sandman before occurred a second later and sort of blew my mind. Williams is such a natural fit with the series that it’s almost creepy. He’s the consummate jackdaw artist, able to shift styles on a dime, deliver pastiches on cue, and give every segment of a story like this a new style while still uniting them visually. Sandman is, by design, a series that leaps from era to era, from one influence to the next, so having someone like Williams along makes it feel like this comic is just reaching new levels, as great as it’s been in the past.

Look, there are warning signs out there. Besides the aforementioned editorial dodginess at DC, there’s the fact that Gaiman simply has never been as great since he left comics for novels and movies (I mean, did you read The Ocean at the End of the Lane? What a lump of blandness). And I know that in many circles, Gaiman’s coolness is at low ebb. He’s become the poster child for annoying fandom, along with Joss Whedon, and it wouldn’t be hard, if you squint a little, to view the guy as a sellout who keeps recycling a certain empty style to the same fanatical fanbase, a la Tim Burton.

But for all that–and I agree with it, to some extent–Sandman remains a masterwork, and this comic shows every sign of fitting right in with the old stuff. I can’t even pretend to be objective about it, as is hopefully clear by now, but this sure as hell doesn’t feel like a disappointment or a desecration of a classic. It feels like Sandman returning, as if it’s never been away. Suddenly, it’s right back where it started, and whatever the existential problems for the character, for the reader, it can only be a delight.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Hellboy: The Midnight Circus HC (Dark Horse, $14.99)

Hellboy: The Midnight Circus HC (Dark Horse, $14.99)

By Adam X. Smith

For the record, the most recent Hellboy collections I had read previous to this were “Conqueror Worm” and both volumes of “Weird Tales” – that’s nearly ten years of comics I’m behind on. Yeesh.

In the chapter notes of the Right Hand of Doom collection, Mike Mignola notes that the short comic “Pancakes” was his reluctant, joking response to being asked to do a story featuring a young Hellboy, and while that three-page story proved popular and does have a remarkably simple but effective gag at its heart – Hellboy is given pancakes for breakfast, Hellboy eats said pancakes and loves them, the assembled legions of Hell reel back and howl in horror at the knowledge they can never win Hellboy back now – with the exception of an Eric Powell strip in Weird Tales #2 and a cameo in the prologue of Hellboy II: The Golden Army, for the longest time, that seemed to be it for young Hellboy’s antics.

Until now, that is. With The Midnight Circus, we go back to Hellboy’s formative years as a somewhat unconventional military brat, still only a kid, sneaking off the BPRD reservation one night to see the outside world and stumbling upon a mysterious circus populated by unearthly beings who will figure into his life in ways he is yet to fully comprehend and who seem determined to work an agenda against him that will continue to plague Hellboy into his adulthood.

While Mignola writes this story – and his fingerprints are all over this story – the art duties are handled by Duncan Fegredo. Being unfamiliar with the way the Hellboy canon had progressed in the time I’d been away, this worried me somewhat – that Mignola had become spread so thin by the now-considerable scope of his universe that he was running roughshod with the hired help. What a fool I was not to trust the man who asked John Byrne to script “Seed of Destruction” due to his own inexperience as a writer at the time, the man who introduced me to the likes of Jill Thompson, John Cassaday and Eric Powell through their appearances in Weird Tales, who continues to entrust the franchise’s artwork to the likes of Fedrego, John Arcudi and Richard Corben as regular artistic collaborators. These are not the actions of a man who doesn’t know how to keep his house in order.

And what a job Fedrego does, in collaboration with colourist Dave Stewart, at putting the mind of the semi-casual Hellboy reader at ease by skewing just close enough to Mignola’s house style to set up the premise, before suddenly skewing away from the pastel four-colour block colours and chunky lines of classic Hellboy into a watercolour wash reminiscent of Tim Sale’s beautiful work (also coloured by Stewart), with the Midnight Circus and its inhabitants existing almost in a parallel realm from the “regular” world. Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio is evoked in both the text and the narrative structure, with the carnival barker (regular demonic adversary Astaroth in disguise) pointing out that the puppet simply “lacked vision”, and seems intent on wooing Hellboy back to the dark side, while his niece Gamori is intent on destroying Hellboy instead, fanatically convinced that he will prove their undoing in the long run.

It is clear that Hellboy as portrayed here – sneaky enough to escape B.P.R.D. headquarters, full of boundless energy and wonder but ultimately innocent and childlike – has become Pinocchio, and as with so many other children in fairy tales, is experiencing his own rite of passage. He’s sneaking away from his home for reasons that aren’t explained – boredom and isolation, perhaps? He steals and smokes a cigarette, starting a long infatuation with smoking while swaggering around like a badass – why? Well, this is what he has learned is the appropriate way to rebel from his limited educational resources (mostly comics, television and boy’s own adventure stories) – the urge to sneak out at night, smoke with impunity and run away to join the circus has crossed every angry, confused or upset child’s mind at least once or twice, and Hellboy is the ultimate outsider.

But this toxic, self-deceiving view of maturity has to stop being a motivator at some point, and in the story it does indeed tell us that – in the majority of cases, at least – when made to actually think about their actions and their effect on others, children are capable of guilt and feeling ashamed for worrying their parental figures, and it is Hellboy’s sudden pang of guilt for his surrogate father figure, Professor Bruttenholm, that catalyses his desire to return home and forsake the circus life. By invoking both the storybook and film of Pinocchio, Mignola and Fedrego have managed to tap into something primal and powerful from this writer’s childhood and reinvented it superbly.

So why does it feel so bad that I can’t just give it a perfect review and leave it at that? Well, if I had to pick fault with the graphic novel – and I literally have to do that or else what’s the point – it would be that it feels ever so slightly too short; not underwritten for sure, but definitely on the short side for what is only the second graphic novel in the over 20 year history of the series. However, what it lacks in length and filling, satisfying reading, it makes up for with the promise of greater electricity to come due to a revelation that for me reframed the previously assumed status quo of Hellboy immensely, and brought everything I thought I knew about the arc of the current storylines right back into question again. And I suppose as a refresher for those unfamiliar with where the franchise has gone in the past decade or so, you could do far worse.

In summation, Hellboy: The Midnight Circus is not getting out of here without a strong recommendation for any of you who grew up with the story of a funny little puppet that wanted to be a real boy.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

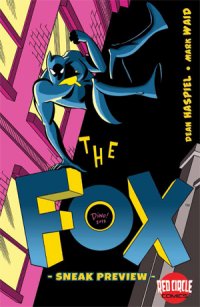

The Fox #1 (of 5)(Red Circle Comics, $2.99)

By Graig Kent

About once or twice every decade, there’s a stab at resurrecting the Red Circle/Archie Adventure heroes, but it never quite sticks. DC made a stab at incorporating the Archie heroes into the DCU a few years back, just prior to the New 52, but that effort didn’t even make it to the 2-year mark. Archie Comics is, for the first time since the early 1980’s, putting a concerted effort into making this superhero universe a go, and they’re doing so not by flooding the market with new titles, but finding creators who actually have a story that they want to tell with these characters. How novel.

I wrote about the flagship title, New Crusaders, last year around this time , and while I found it to be highly disappointing and slightly amateurish, I have to admit its writer certainly seemed to have a story he wanted to tell and a passion for the Archie heroes that I could identify with. Likewise, industry veteran Dean Haspiel comes at the long-dormant property, The Fox, with an idea in mind, a personal connection to the material, and an acknowledgement of his own limitations.

Paul Patton is a photojournalist who adopts the guise of The Fox in order to, essentially, create the story. In the process of taking on a superhero identity, Patton inexplicably becomes a “freak magnet”, whereby strange people and events seem to be drawn to him. I like this setup, true to the original Fox established in the 1940’s, a hero who uses his costumed adventuring to advance his alter ego’s career… and this was well before there was a Peter Parker. At the same time, the character is naturally treading a gray area where, as a journalist, he’s in theory making the story rather than finding it. This idea, unfortunately doesn’t even seem to register, at least not in the first issue of this mini-series. Patton is a married man, with a wife that seems to support both of his careers, and I imagine this was written before, instead of as a reaction to Dan Didio’s recent anti-marriage stance on superheros. He’s a hero certainly willing to take his lumps, plus he’s clever enough to think many steps ahead of his opponent, though he’s regularly taken by surprise. I like him based on all these facets of his character, and while they are all served up in this one issue, the story just doesn’t seem to do him justice.

Where the character feels warm and inviting, the story itself feels thin. Nothing happens in this book’s first 18 pages that is fresh or captivating. There’s a tame weirdness that never surprises nor truly engages. Given the promotional imagery I had seen, including the front cover to this issue, I was expecting more of a Mike Allred-style pop-art costumed hero experience, more of a Madman vibe. Were that more the case, this book would shine, but beyond the front cover, Haspiel plays it fairly straight artistically, and at times his simplistic cartooning is downright clunky instead of the dynamic POW! BAM! Toth/Kirby zip it needs.

Haspiel, in the backmatter of this first issue, serves up an essay on his personal history, and how it connects with the character and the story. In Paul Patton, Haspiel sees his father, also a photographer, and a man who encountered a lot of conflict, so there’s a personal element to what the story presents. Haspiel is also aware that he’s not as strong a writer as he would like, so working the Marvel style, he plotted the story, drew the pages and asked writer extraordinaire Mark Waid to fill in the script.

Waid’s scripting is flowery enough to be amusing (even getting another dig in at the cinematic Man Of Steel) but it doesn’t save the weak story that it hangs upon. Once more I went into an Archie Adventure Heroes endeavor with great anticipation (I have an admitted abnormal affection for them) only to be disappointed again. The Fox is not a complete writeoff, but the next issue has to have a lot of bounce for it to really rebound.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

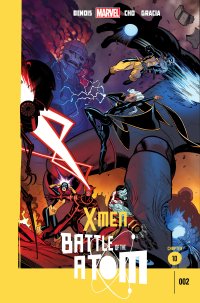

X-Men: Battle of the Atom #2 (Marvel, $3.99)

X-Men: Battle of the Atom #2 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

So, here we have the unusual situation of a corporate comic book crossover epic ending after, technically, only two issues; other similar “events” may have felt as though they had more tie-in books than the event itself, and sometimes did, but to have the “main” miniseries represent something like a fifth of the overall storyline is noteworthy, to say the least.

Also noteworthy is that choice of the creator names to put on the cover–“Bendis / Cho”– would seem to represent an unscrupulous attempt to deceive those who desire cascades of word balloons and/or busty women with Lynda Carter’s face, since Brian Bendis contributes only a brief epilog, and Frank Cho is nowhere to be found. In fact, it seems to indicate deadline pressures that also resulted in Cho being “replaced” by no fewer than thirteen artists, resulting in exactly the sort of gloppy mess that would suggest.

Though Bendis makes an appearance here, Jason Aaron is the principal scripter; like Bendis (and, say, Ed Brubaker), Aaron’s crime-writer instincts are at their best with one or two central point of view characters, placed against an absurdly challenging backdrop: his near-impossible feats for Marvel have included following Garth Ennis on Punisher MAX, and making both Wolverine and Ghost Rider characters worth reading about again. But the sprawling X franchise has long operated on its own version of Raymond Chandler’s dictum: “When in doubt, have a mutant come through the door with a new power,” and sometimes even Aaron seems to get lost in the crowd: I would defy any non-X fanatic reader to pick up this issue and get not only who all these varied characters are (including original X-Men, 70’s-era X-Men, X-Men from the future, and bonus mutant persons), but what their agendas and motivations are without some research. Some of that, naturally, comes in the various issues of X-Men, Uncanny, etc., that make up the bulk of this crossover, but the old cliche of “Every issue of NAME OF COMIC is someone’s first,’ applied here, would likely insure that this was also someone’s last. That’s obviously part of the marketplace challenge in serialized storytelling, but it ought to be possible for someone to go from issue 1 to issue 2 of a miniseries without needing to have the latest version of the Marvel Universe Encyclopedia handy.

No offense to Lee and Kirby, but the tightly-plotted, emotionally resonant, X-Men of the Claremont/Cockrum/Byrne era remain the series’ standard, but this issue drives home how that template of mutants versus “straight” society has pretty much ossified the concept: at more than one point in this issue, we have characters bleakly stating their belief that this “Man versus Mutant” conflict is all that they have to look forward to, on into the future, and while it’s intended to serve as a rallying cry, it’s also a grim reminder of how the X readership rewards the constant reiteration of the same storylines and broken romantic couplings over and over–hell, in this issue, we get more fucking Sentinels, this time evidently owned and operated by SHIELD (though it’s likely the old “rogue splinter element” since Maria Hill seems astonished by their existence).

I know that Disney/Marvel is moving towards convergence in all media, hence the tortured plot twists around excess time travel having “broken” the timeline, but making the X-Men and Avengers franchises feel virtually interchangeable devalues the unique strengths that the mutants once possessed.

If you haven’t been reading this crossover so far, we’ve got X-Men past, present, future, and evil, spouting exposition at each other as they engage in a mega-spandex showdown. And while solicitations promise us yet more X-deaths in this issue, this is somewhat undercut by the fact that several of the characters have multiple versions of themselves running around here, and Aaron and company selectively kill off the least commercially viable version of each (though Ilyana manages to fly into one of her black-magic rages no matter which version of her brother gets sacrificed). In the end, it’s X-status-quo-ante: still split along vaguely articulated dogmatic lines involving assimilation versus resistance, with some characters stomping off in mutant huffs while others weep for the future.

When he can find a quiet moment, Aaron actually manages some nice character work: the farewell scene between Shogo and not-dead Jubilee carries a hint of the best Claremont/Whedon style soap opera (though only regular X readers are likely to even understand the relationship). As crossovers go, it was relatively swift and painless; as comic book storytelling, though, it seems like a lot of effort to wind up basically back in the same place.

I’ve put off talking about the art mostly because it’s pretty much a mess: it feels like the rush job that it probably was on the part of such veterans as Esad Ribic, Stuart Immonen, and Chris Bachalo. The main story suffers the most, with Ribic and co-penciller Giuseppe Camuncoli providing breakdowns for Andrew Currie and Tom Palmer on finishes (there are also three credited colorists for this one). The size and scope of the battle means there’s the occasional epic splash or smashdown, but you’ve seen better from all concerned. The three “epilogues” at least have more consistency of style, but there seems to have been little time for anything but workaday professionalism from artists who are capable of much more.

Collected in trade form, the throughline of this event may overcome the wild inconsistencies in tone between titles, and within this one issue, setting up the next year’s worth of mutant merriment. Or you could just wait and pick up Amazing X-Men #1, and find out how fucking Nightcrawler comes back from the dead.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars