Professional wrestling, even now, is not a medium celebrated for respecting the intelligence of its fans. No single moment contextualizes this sentiment more readily than 1990’s WCW PPV extravaganza Capital Combat: The Return of RoboCop: a cross-promotional feat so egregious that even Goebbels would have to concede it ill-advised.

Professional wrestling, even now, is not a medium celebrated for respecting the intelligence of its fans. No single moment contextualizes this sentiment more readily than 1990’s WCW PPV extravaganza Capital Combat: The Return of RoboCop: a cross-promotional feat so egregious that even Goebbels would have to concede it ill-advised.

Pro wrestling was no stranger to cozying up with the movie business, even if the favor wasn’t always returned. Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling ran Captital Combat a full year after Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Federation made its first foray into actual moviemaking with the Hulk Hogan vehicle No Holds Barred, a film Gene Siskel was kinder than he needed to be towards, saying “sometimes when you put what already is a parody up on the big screen, it falls flat.” But warnings were not heeded (ever, see WWE-produced The Call) and Ted Turner’s promotion made in-roads at bringing RoboCop to the D.C. Armory in Washington D.C. for May the 19th of 1990.

This was a full six years before WCW achieved grand international success with its NWO, establishing the “cool heel” (heel being the wrestling terminology for bad guy) in personalities like Hollywood Hulk Hogan and Big Sexy Kevin Nash. Before that, WCW was basically a southern territory with a bigger pocketbook. WWF’s Rock n’ Wrestling movement of the 80s, one that saw MTV stars like Cyndi Lauper appearing on show’s like NBC’s Saturday Night’s Main Event, was quieting even as WWF still held a vicegrip on the national spotlight. Even so, pro wrestling as a whole was trending downwards and getting desperate for the sort of ratings grabs that would lead to a debacle like what we have here.

WCW, even during its most successful run, was never not in some form of backstage turmoil. Turner (whose empire had assumed full control of the promotion by 1990) was happy to be the absentee landlord, preferring his merry band of human action figures run by committee with minimum booking interference. But the business end always clashed with the nomadic nature of the wrestlers, roving backs of man-children calling themselves “the boys” and living one gig to the next. Forcing a cross-promotion of this magnitude, especially something so glaringly wrong for the business, was certain to play out painfully if it ever made its way to a pay-per-view stage.

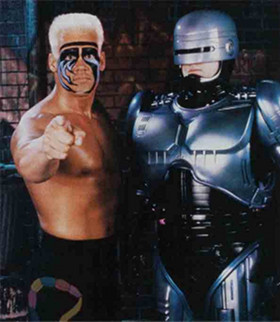

Turner’s suits no doubt thought they were on to something special. For all of its R-rated roots, RoboCop had nevertheless been adopted by children as a viable brand, spawning all manner of action figures, videogames and even an animated series. By the time RoboCop 2 (a film where a child’s head is crushed by a drug-addicted Go-bot) was approaching release, the suits overseeing WCW thought it wise to appeal to a wider audience with a big-time Hollywood stunt. Sting, on the other hand, was WCW’s younger, more agile answer to Hogan. Something of a cross between Hogan and Ultimate Warrior (but with actual wrestling talent), Sting would “Whoo!” and strut to the ring in with a bleach-blonde crewcut that sat atop some very bright, neon facepaint.

By ’90, Sting had found himself in the main event scene battling the likes of Ric Flair, the man in WCW at the time. Flair had paid his dues all over the world and had come to prominence the old fashioned way: solid mic work serving some of the purest in-ring work the business had ever know. Flair would have been second only to WCW President Jim Herd, a former St. Louis station manager appointed by Turner to outfit his promotion into something that could compete effectively with McMahon. In management’s eyes you had the hero of the promotion trying to stick it to a conniving villain who always seemed to gain the upperhand. The higher-ups needed something that could draw mainstream press but still effectively continue the storyline – WCW’s main cashcow of the era.

If your answer to this grand setup is “Get RoboCop,” congratulations. You’d have likely been fired too.

Flair ran a pack of heels and yes men termed the Four Horsemen, to this day one of the most successful and enduring stables in wrestling history. Captital Combat was to see Flair facing Lex Luger, Sting’s best friend and former tag partner, for Flair’s heavyweight title. Trouble was Flair’s character was a cheating, backstabbing sonofabitch who always found a way to leave with the title in hand. But Sting had a plan to even the odds in Luger’s favor, he called his pal Alex Murphy. Because naturally pro-wrestlers have fictional robot men on speed dial.

Sting began appearing on TV, letting the Horsemen know they’d made a big mistake messing with RoboCop. This had to come to the surprise of Flair and his cronies, considering up to now they believed RoboCop to be a character in a film and not an actual cyborg man fighting crime and peeking on his wife in Detroit, Michigan. Turner began airing a series of promos putting Sting side-by-side with their company’s big get, threatening an epic showdown come the night of the event.

Fans had to be forgiven for not connecting the dots until it was too late. No way was WCW going through with this. It was a gross violation of common sense at a time when wrestling, though it hadn’t been viewed as legit sport in years, was still murky in regards to admitting its own lack of authenticity. Having wrestlers react realistically to a character both they and the audience perceived to be fictional was in actuality the clusterfuck it had every right to be. At a PPV called Capital Combat in Washington DC, WCW decided there was nothing more American or patriotic then Alex Murphy tearing open a cage to save his bleach blonde buddy; it was a chemical reaction that could only be referred to as “drugs without drugs:”

RoboCop’s presence heralded the beginnings of another dark period in WCW’s history. Jim Herd was eventually let go and, to this day, is viewed as one of the worst minds in professional wrestling history. Flair got tired of playing second fiddle to robots and jumped ship to McMahon’s WWF, taking the heavyweight title with him in what had to be one of the more embarrassing coups from WCW’s perspective. And yet it was RoboCop who suffered the worst. While by no means the straw that broke the camel’s back, Capital Combat signified the beginnings of a hex on the beloved character. Two sequels of marginal quality, a middling TV series and deplorable Canadian TV movies would mire the character for the next two decades.

Few mediums go worse together than science fiction and pro wrestling. Like two positives equalling a negative, these two distinct models require suspension of disbelief from the able viewer. But an audience can only travel down the rabbit hole so far, especially when it begins pulling you in two completely different directions. Capital Combat serves as a glaring example of entertainment getting it wrong.

Of course WCW wouldn’t learn their lesson, hosting killer-doll Chucky on the show some eight years later. But don’t expect Joel Kinnaman to show up on Raw any time soon.

Twitter

Facebook

E-Mail

Source: Thanks to Jamie Williams of Think Mcfly Think for reminding me about this historical event.