Day One – The Shining / Day Two – Full Metal Jacket / Day Three – Eyes Wide Shut

Day Four – A Clockwork Orange / Day Five – 2001: A Space Odyssey Mesage Board Discussion

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE

STUDIO: Warner Bros.

MSRP: $79.98

RATED: G

RUNNING TIME: 149 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

- Theatrical trailer

- Commentary by Kier Dullea & Gary Lockwood

- 2001: The Making of a Myth

- Look: Stanley Kubrick!

- 1966 Kubrick Audio Interview

- 2001: FX and Early Conceptual Artwork

- Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick

- Vision of a Future Passed

- 2001: A Space Odyssey – A Look Behind the Future and What is Out There?

The Pitch

The most important and influential science fiction film ever made. Is that enough for you?

The Humans

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Cast: Keir Dullea. Gary Lockwood. William Sylvester. Douglas Rain.

Writers: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke

The Nutshell

A monolith’s appearance in ancient times leads towards an awaking in primate man, a monolith on the moon leads towards a new awakening in modern man. The cosmic meets the real in Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s painstaking, deliberate, and mindbending film which paved the way for pretty much every major cinematic science fiction entry which followed. That’s not hyperbole either.

The CHUD.com Staff Ruminates on 2001: A Space Odyssey:

Random

Thoughts on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I never watched 2001: A Space Odyssey while high. I have watched a lot of movies while high on

various substances (Mazes and Monsters got the biggest bump in quality from

drugs, by the way), but the one film that seems to be made for toking or dosing

is the one for which I’ve stayed sober. I guess I’m perverse like that.

There’s a woman who lives in the apartment complex next to mine, and her

balcony overlooks my bedroom window. She’s old, and smokes all day and begins

every morning by coghing and spitting and bringing up huge splattery loogies

from the cancerous depths of her lungs. I always wish that if another

black slab came to Earth it would land on her head. She doesn’t deserve to

get to the next level of evolution.

When I’m really drunk and feel myself fading, I tend to sing Daisy. Most people

don’t get it.

One thing that has always bugged me about 2001: A Space Odyssey is that the cut from the bone

spinning in the air to the spacecraft in Earth orbit isn’t exact – the bone and

ship are at different positions. I’m not usually this anal, but I have a

feeling that if Kubrick made the film in the 21st century he wouldn’t call it 2001: A Space Odyssey. Also, he’d use computers to get that famous jump cut perfect.

It’s one thing for a film to lay claim to a modern pop song – that music is

newer and has fewer associations, and is malleable in the public consciousness.

But with 2001: A Space Odyssey Kubrick lays claim to whole swaths of classical music; Also Spach

Zarathustra will be linked, forever and ever, with this film. It’s one of the

most direct and obvious examples of the overwhelming power of cinema.

Unlike

most of Stanley Kubrick’s films, which bring to mind a stream of images and

impressions, 2001: A Space Odyssey is keyed in my mind to one edit. A single juxtaposition of

images speaks more than the entire output of other filmmakers: a bone followed

as it tumbles through the air, becoming in a couple of quick cuts a human-built

craft floating in space. Just as Russia and America were racing to achieve what

was then mankind’s greatest dream — the first step in the conquest of space —

Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke negated the accomplishments of an entire species

in a single second.

I’d

like to think that Kubrick would include his own films in that all-encompassing

edit. If so, that would imply the presence of a sense of humor, which audiences

perpetually claim is missing from the man’s films. And while that edit places

the focus of the film squarely on human evolution rather than any

techno-worship, there’s an undeniable current of grinning aesthetic

appreciation for human products in the film. Why else would we be shown a

forest of red chairs squatting like brilliant mushrooms, or a father-daughter

conversation that spans thousands of miles? And no one cuts a shuttle’s docking

approach to the Blue Danube Waltz that has the negation of technology as a

primary concern.

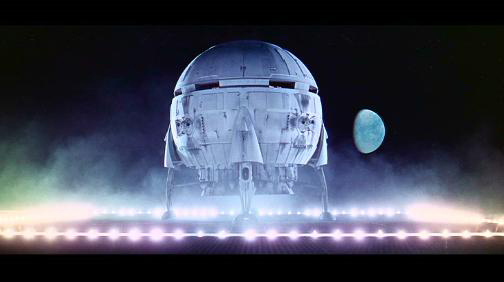

When

I sat down to write this piece, the first thing I crossed off the list of

potential topics was the pure beauty of the film. But scanning the Blu-ray disc

for these images of techno-appreciation I’m temporarily blinded to deeper

concerns. It’s not enough that Kubrick made the first amazing space FX movie;

he crafted it so well that when presented in high definition (whether that be

70mm or 1080p) there’s not a flaw to be found.

I’ve

watched this entire batch of re-releases in HD and they all look great, but

2001 is mind-boggling. The perfectionism for which Kubrick was famous emanates

from every frame; the incomplete space station and functional appearance of the

Jupiter mission’s craft, Bowman’s visions and the film’s final moments in this

presentation are more impressive than ever, because they’re each a diamond

gleaming out from the screen.

(Seen

in 70mm the effect is probably the same, but I’ve never been so lucky. In fact,

while I’ve seen every other major Kubrick movie from The Killing to Eyes Wide

Shut on a movie screen, I’ve never seen 2001: A Space Odyssey projected in any format.)

Some

people are flattened by music or editing, but the unity of on-set craft is what

always grabs my attention. So these practical effects, so simple and effective

that a modern movie-savvy audience won’t be able to figure them out, are as

glorious now as ever. (Show ten people the floating pen bit and see how many of

them know how it was done without CGI. Three in a smart sample.) I don’t’ have

to hesitate at all in calling 2001: A Space Odyssey closer to technical

perfection than any other film. That

statement can be made and supported without even beginning to engage Kubrick’s

marriage of form and content, which is another massive achievement altogether.

– Russ Fischer

The first time I watched 2001: A Space Odyssey, I was in the company of someone that was

baked out of their mind. Listening to their running commentary during

the film cost me a lot of opportunities to really dig into one of

Kubrick’s masterworks and I’m forever plagued with snippets from that

first viewing. The one that sticks in my memory and comes up whenever I

see the flick is the friend’s comments about the finale. It wasn’t

anything dumb about the Spacechild or the light show that marks the

beginning of the Third Act.

He leaned over to me and said with the straightest face, “I liked it

better when it was about the monkeys”. The fact that he could look past

everything that was place onscreen and boil down the entire film to a

band of monkeys blew my mind. So, when I think of

that comment. Thank you, man. Eight years later and you’re still

ruining movies for me.

Writing about 2001: A Space Odyssey is a lot like writing

about The Bible. There isn’t much to say that hasn’t already been said

by someone else, since it’s generally considered one of the best films

of all time. That said, it’s also pretty easy to write about, since the

film is so thematically broad, covering such wide-ranging topics as

evolution, artificial intelligence, alien life, technology, and ape

fights. It also has the distinction of being the most over-parodied and

over-referenced of all of Kubrick’s films (see Spaceballs, Red Dwarf, Stealth, The Jerk, Airplane II, and the infamous 1976: Disco Booty Odyssey). I could probably recreate the entirety of 2001: A Space Odyssey in cartoon form by collecting and editing Simpsons references alone. A good starting point for a discussion might be: “What makes 2001: A Space Odyssey so deeply ingrained into our popular consciousness?”

My answer: 2001: A Space Odyssey is

like the world’s most popular piece of experimental classical music,

and is so different from anything that ever came before it (well,

besides maybe Metropolis) that it was permanently shocked

into our consciousness. It’s an entertaining, gorgeous, sometimes

baffling vision of the future, and plays differently every time we see

it. While the ending of Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey novel isn’t as ambiguous, what we take away from the film version is entirely up to us; 2001: A Space Odyssey’s

ending is perhaps the most widely seen

“what-in-the-fuck-is-going-on-here” moment in mainstream film. Like any

other good piece of music, it’s entirely subjective, which is why it’s

still popular amongst modern cinephiles and pot smoking teens alike.

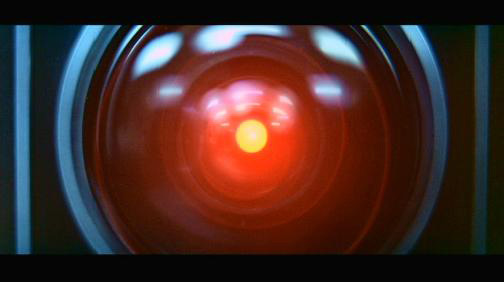

Oh, and 2001: A Space Odyssey’s HAL paved the way for Colossus: The Forbin Project’s Colossus.

While HAL’s the better ‘character’, Colossus is just so much more

menacing. Colossus makes HAL look like an infected Mac in a high school

media room. Colossus is so bad that his disk space is measured in

Cenobites. In Colossus: The Forbin Project, Colossus teaches Dr. Forbin how to make the perfect martini. In 2001: A Space Odyssey,

it’s not clear whether or not HAL even knows what a martini is, let

alone how good his mixing skills are. I probably wouldn’t even let HAL near the liquor cabinet. If you take anything away from these three paragraphs, it should be this: Colossus needs more respect.

I have seen the film all the way through in one sitting three times before this month. I have now seen it all the way through about seven times and it has become a lovely part of my filmic routine. Its pace and silence married with its sudden sounds and usage of classical music is something I find to be a great bedrock for when I’m working, cleaning the house, or discovering little monoliths in the scalp of my mate. I don’t know why or how I turned the corner on this one, especially since I had planned to use this series of articles as a reasoning why this film isn’t figuratively all that. Except it is.

Such a fucking special movie, one I found boring as hell as recently as five years ago. Once again, as is the case with many of Kubrick’s films, I respected it and found it to be a transcendent piece of history but didn’t go out of my way to watch or recommend it. In film school it led to one extremely long and punishing experience where I thought I’d never watch the film again for as long as I lived.

Now I can watch it without feeling unrest or bored. Have I gotten old, smarter, dumber, lazier, or just more Italian? I don’t know. What I do know is that this film is fucking knockers and I wish I had given it the open-minded time a long time ago.

Oh, and I don’t get high and I still love it so there’s that.

– Nick Nunziata

2001: A Space Odyssey is a movie that I find something new to digest with every viewing.

Back in 1982 my mother took me to a dollar cinema and along the way she

kept trying to explain to me what the movie was about. "You’ll see some

monkeys but this is NOT just about them", "You’ll have lots of

questions afterwards". She seemed so excited about sharing this movie

with me I was getting worried and ask myself "What if I don’t like it?"

For the first time in my young movie going experience I just sat there

in awe and even though I could not grasp the deeper meaning of

could at least appreciate the fact that I was watching something

amazing. After the movie was over and we had gone back to the car Mom

was sitting there all wide-eyed waiting for me to overload her with

questions. What did I do? I just sat there looking back at her

wide-eyed with no questions. For a moment I thought she was going to be

disappointed and then she just grinned. The look on my face was all she

needed to see as she knew that what I had just experienced with a movie

was something special.

Until last summer, I had never been able to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey in its

entirety. I tried over a dozen times, at least, but the same thing

happened—twenty or so minutes in, right around the end of the ape

sequence and the beginning of the “Blue Danube” docking bit, I’d fall

right asleep. Without fail. I’d probably seen all the relevant clips,

thanks to awards shows and Kubrick documentaries, but I’d never seen

the flick whole, and from someone who considers himself to be a serious

film fan, this bugged me. Last summer, that all changed. A friend and

I, armed with Red Bull and a few other substances I’d rather not

mention, sat down, and we watched the whole fucking movie.

It was one of the great experiences of my film-going life.

This is a movie that dares you to stop paying attention, to fall

asleep, in effect, because of how revolutionary it is. It’s not a

traditional science fiction film by any means. It’s not even a

traditional “film”—I’ve never seen so many narrative conventions either

missing or askew as they are in

Watching it for the first time, it seemed like Kubrick’s got nothing

less on his agenda than to transport you to another world, and a return

voyage is less-than-assured. Sure, the learning curve to get into his

world may be tough (and soporific). But I can’t think of any film more

worth the effort.

– Josh Katz

about six years old. I loved science fiction so she figured it was set

in space, in the future, so why not? Except of course the

science-fiction I was a fan of at the time featured either Wars or

Treks in their titles and after about ten-minutes of monkey skull

bashing (“Is this Planet of the Apes?” my dad asked) the movie got shut

off right quick.

Years later in high school, after watching A Clockwork Orange and The

Shining, I returned to

movies. Movies stopped becoming movies after 2001: A Space Odyssey and started becoming

film. I wasn’t aware of poetry in the cinema before 2001: A Space Odyssey. I wasn’t

aware of how much you could do with a film, what you could suggest,

where it could lead analytical thinking. The film’s tag-line might have

been “the ultimate trip” to cash in on the acid-dropping crowd of the

late 60’s, but it’s universally appropriate. Not only does it factor

into the plot, it represents a shift in movie-making (and for me,

movie-watching). You’ll never see another movie like 2001: A Space Odyssey, so in some

ways, it’s the movie to end all movies, charting the ultimate human

story, from pre-evolved ape to reborn star god. How fitting that a film

about evolution and the triumph of humanity over machinery was my

gateway into the real, beautiful possibilities of film and cinema being

looked at as an art form rather than simply entertainment.

There’s a famous story about the premiere of 2001: A Space Odyssey,

a story I’m sure at least some of you are familiar with: Supposedly, at

the film’s world premiere, Rock Hudson stormed out of the theater

halfway through the screening, shouting "Will someone please tell me

what the hell this movie is about?" I can relate, Rock. The first time

I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey as a teenager, I pretty much had

the exact same reaction. What the hell am I watching? I thought this

was supposed to be a science fiction movie! Where are the ray guns?

What’s with all the guys in the monkey suits? And for the love of God,

why’d they have to make the thing so boring? I simply didn’t understand the movie. And I didn’t understand why it was considered such a masterpiece. Star Wars, now there was a masterpiece. 2001: A Space Odyssey,

as far as I was concerned, was just a movie people said they liked so

they could sound smart. No sane person could possibly find this movie

entertaining, I reasoned. They all had to be lying.

It’s amazing what a difference fifteen years makes. Today, I can’t fathom how someone could watch 2001: A Space Odyssey and not be

entranced by it. It’s a testament to the film’s effectiveness that even

back then, watching the movie at thirteen years old and bored to tears,

I simply could not change the channel. Oh sure, I rationalized it away

at the time: I just wanted to see how it ends, I told myself. But that

wasn’t it. The movie is just so damn engrossing that you can’t turn

away, no matter what your opinion of the film might be while you’re

watching it.

I have to admit, even now I’m not sure I fully understand this movie. I

don’t think I ever will. But while once I found that frustrating, now I

realize that this lack of understanding is exactly what’s so riveting

about 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s not a movie that’s meant to be understood on a

literal, narrative level. Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark both

recognized that for something to inspire awe, it must also be totally

incomprehensible. After all, once mankind was able to scientifically

explain the sun and the moon and their relationship to the Earth, we

stopped looking at those objects with any sense of wonder. What’s to

wonder, now that we know it all? In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick gives us

those monoliths which, in spite of the fact that they’re completely

inanimate objects, still manage to inspire both terror and wonder

because they’re just so damn inexplicable. After everything we see over

the course of the movie, by the end we’re not much closer to

understanding the nature of the monoliths as we were at the beginning.

As much as we’d like to think that we as humankind understand the

universe around us, 2001: A Space Odyssey shows us a version of ourselves that

is probably closer to the truth: That we are, in the grand scheme of

things, completely ignorant. Kinda like my thirteen-year-old self.

I had the good fortune to be born to a movie lover. I almost saw 2001: A Space Odyssey

for the first time when I was six or seven years old– Mom herded me

and my brother into the car when she found out it was playing locally,

only to cancel said excursion at the concession stand upon being

informed that the multiplex’s main screen was being occupied by Midway,

in Sensurround no less. We could hear the explosions from there, so it

was an easy call. Nevertheless, it would be at least two years before

another opportunity presented itself, and by that time Star Wars

had happened. I’d begun to educate myself in the art of special

effects, and I’d gleaned the basics of miniature photography,

compositing, and motion-control from an excellent article in Dynamite magazine. I vivdly remember watching the ‘Blue Danube’ sequence for the first time and asking myself, wait–

this looks really good. If this stuff was done ten years ago, what’s so

special about John Dykstra’s innovations? Aha– Kubrick’s guys are

working at the absolute limit of their capabilities. They’re not moving

the camera very much… There’s no perspective shift on that

satellite–it’s just a still image… The spaceships never pass in

front of the planets… That miniature there must have been absolutely

enormous… Perhaps Big Stan would have been surprised that a

nine-year-old kid was watching his work with such minimal suspension of

disbelief, but I doubt the old misanthrope would have been disappointed. If it’s any consolation, I was totally sold on Stuart Freeborn’s ape-men.

When one

hears Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey referred to as "The Ultimate

Trip", the implication is that the film goes down best with some ingested

hallucinogenic something-or-other. I’d

say it goes down different, and add that this chemically/herbally/gerbilly

enhanced state is most acute when viewing the film in 70mm – the essential

presentation for 2001: A Space Odyssey. In an enormous

theater with state-of-the-art sound and a receptive (i.e. hushed) audience,

Kubrick’s vision immerses the viewer in a strange, richly imagined world that,

narratively, makes more sense intellectually than it does emotionally. It challenges the audience, and, unless one

feels compelled to bolt for the exits after too much ape-man drama, requires

them to rethink the purpose and scope of storytelling. There had obviously been epics before 2001: A Space Odyssey,

some of which may have covered close to the same amount of temporal distance

over the course of two or three hours.

But how many had merged the Dawn of Man with the Space Age in one

cut? And commented on the basic,

unstoppable nature of human ambition in the very brief process?

That would

be a big goose egg.

My first few

passes at 2001: A Space Odyssey were on a small, 4×3 television like most kids my age, but it

wasn’t until I moved to New York City and saw the film presented at the

majestic Ziegfeld Theatre that I truly experienced 2001: A Space Odyssey (sans any chemical

assistance save for maybe a fast-food lunch).

And while I know many of you don’t get that kind of opportunity, it is

well worth traveling a few hours *once* in your life to see 2001: A Space Odyssey in full. I don’t necessarily think you’ll derive a

fuller understanding of the film this way (indeed, the film’s themes may shake

out more clearly in miniature), but you will experience about twenty to thirty

"holy moments" that will last you the rest of your days.

Orson Welles

called 2001: A Space Odyssey "The biggest electric train set a boy ever had." Nowadays, I don’t know what’s rarer: grandiose filmmaking or model train

collectors.

2001: A Space Odyssey is all things to all people, kinda like God but

with less exposition. It was my favorite film for many years. I have

since surrendered the notion of a steadfast favorite film. But during

my years in art school, I was more than susceptible to thinking as

abstractly as possible. And watching it again made me believe in art.

That was more than enough.

So, what can be said about it, then? It was bold, brilliant

storytelling. The subject matter was epic in its simplicity. For all of

the chatter about the ending, it’s the Dawn Of Man sequence that is

truly astonishing. The film earns its thematic heft in the first

section alone. But the attention to detail throughout is immaculate.

There is nothing in the film that doesn’t have a purpose. It was a

technical masterpiece, not outdone for ten years in the optical effects

department until Lucas came from a galaxy blah blah bluhblah… It was

a cultural phenomenon, apparently a huge hit with the hoppers and

hippies. And in a small victory for the genre, the film was

scientifically feasible given the story’s basic demands. None of this

e-z bake artificial gravity here. (I’m afraid you’ll have to spin for

it, Dave.) Style wise,

inquisition over rumors of an outbreak by canny Russians lounging in

swank red chairs is a great way to steal some time while en route to

witness crazy alien shit.

Kubrick really developed his reputation as a master filmmaker worthy of

repeat viewings with this one. I could go on about how the ending can

be explained as a visual metaphor for the incomprehensible mindfuck, a

galactic-sized evolution would wreak upon our puny simian brains. And

the hopeful, yet sober message behind the film’s pomp and circumstance

about the power of science; that, ultimately, we must recognize

technology is nothing more than an extension of man, capable of all of

the same flaws. So while science can eventually save us from

extinction, it will occasionally kill us with an EV Pod in the lonely

vacuum of outer space.

However, since the film is 40 years old and been analyzed several times

over, let’s just say that it took many people, many viewings to get to

this point. But that’s just my take. Compared to Clarke’s novel which

offers up less mystery, Kubrick could not have been more clear in his

intentions to be as opaque as possible. Whenever artists, musicians and

authors talk about the relevance of personal interpretation, somewhere

in their minds they’re thinking about this film. At least a tiny bit.

Kubrick makes one of his strongest cases for the importance of asking

the right questions, instead of having all the right answers.

it is arguably the only science fiction film that truly matters. Even

today, it is difficult for me to name a film that has meant more to my

progression as an artist or a free thinker than this one. I even got a

little sentimental when an anonymous artist mysteriously erected a

monolith in Seattle six, almost seven years ago. It might not end up as

my favorite film for all eternity, but it casts a long shadow over

everything else.

One last item of note:

2001: A Space Odyssey has to be one of the only G rated filmswhere almost everyone dies. Hey Eyes Wide Shut— karma’s a bitch, ain’t

it?

The Package

The best special features in the whole Stanley Kubrick collection reside right here, folks. Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood are a terrific commentary tandem, taking the meat of the story and their involvement in the film and presenting it in a very subdued and interesting way. I found myself hitting myself in the head at some of the obvious things they taught me about the themes of the movie. A lot of folks tend to collect stuff from books, the web, or whatever to "form their opinion" of a film or piece of literature or whatever. Many sites like ours and message boards like ours are populated with folks who regurgitate other people’s opinions as a means to sound intellectual. It’s human nature, having been instilled in us on those late-night scrams to get material for a test or report. What’s great about their commentary track is how it really boils away a lot of the analytical stuff that made this film such a daunting one to discuss and distills it to the bare essentials. In some way it’s a very uncomplicated movie and it’s nice to have these firsthand participants be a tour guide through it. Gary Lockwood is a bit egotistic at times, but looking at his IMDB resume, maybe he should tone that down a little.

The documentaries on disc two are numerous, dense, and nothing short of fantastic. Seeing the likes of Spielberg, Lucas, Cameron, and dozens of other luminaries (plus Ernest Dickerson) talk about the film and filmmaker that so changed their lives is incredible. It makes me regret not being there for this film’s release though I’m glad I have the four extra years of youth.

It’s a fantasic immersion into the world of 2001: A Space Odyssey and they really don’t need to quintuple dip this one. I’m satiated.

10.0 out of 10