Hawkeye #7 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

I don’t know if anyone out there was waiting for a better reason to start reading this comic than its engaging mixture of wit, action, silliness, insight, banter, emotional depth, visual audacity and self-contained storytelling… but if so, here’s one: writer Matt Fraction is donating his royalties from this issue to Hurricane Sandy relief. Remember Sandy? Was all over the news just before Christmas? While Fraction wrote this issue in the wake of the storm itself, production lag time means that it hits the stands far enough removed from the event to serve as a reminder that disasters of that type can affect people’s lives for months and years after the event is no longer considered “newsworthy.”

But, hey, don’t buy this issue out of guilt: buy it because it’s another fine issue of the best comic Marvel is currently putting out.

There are two stories here, set during the Sandy onslaught: Clint (Hawkeye) Barton is helping a neighbor try and get his endangered father to safety, while Kate (Hawkeye) Bishop finds herself in a fancy dress at a fancy wedding at a fancy hotel when the storm strikes, and decides that being a superhero trains you for more than just repelling interplanetary invasions. Kate’s story is more in tune with what we’ve come to expect from this series, with an amusing bickering setup between Kate and Clint, a great sequence of Kate plunging (literally) into action (designer clothes be damned), and making some nice discoveries about the interconnectedness of her fellow Jerseyites after a looter cold-cocks her with a can of beans. Clint’s story works to deepen the relationships that the series has established between “Hawkguy” and his New York neighbors, and while no bow or arrow is pulled, more points are made about people’s connections with each other, with a special focus on the kind of family ties that shouldn’t need a disaster to come into focus. There’s humor in the story, to be sure, but it’s honestly earned by the well-meaning, but slightly clunky, persona that Fraction has brought out in Clint.

Given the need to get the issue produced quickly, we have two guest artists: On Clint’s story, Eisner-winner Steve Lieber, with the always fantastic colors of Matt Hollingsworth, does a good job of blending his pencils with the urban setting that the series has established, though the paneling is more straightforward than regular artist David Aja’s dazzling bag of tricks (I’d imagine that time pressure probably made a simpler approach the sensible one). Kate’s story is illustrated by relative newcomer Jesse Hamm (evidently a studio mate of Lieber’s), and his more open, cartoony approach suits the brisk action pacing.

If you’re not yet reading Hawkeye, one of the beauties of this series is that pretty much any issue can serve as a jumping-on point, so compact and crisp is the storytelling. And since a portion of your four bucks this time out goes to a good cause, what are you waiting for?

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Green Lanterns: New Guardians Annual #1 (DC, $4.99)

Threshold Presents: The Hunted #1 (DC, $2.99)

Deathmatch #2 (BOOM! Studios, $3.99)

Avengers Arena #3 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Graig Kent

The Most Dangerous Game, the 1924 Richard Connell story of man hunting another man for sport on an island can be largely credited as the establishing point for all of this… death… that has occurred in the years to follow. The term “the most dangerous game” has, of course, become synonymous for a hunted man, since humans are just as capable of hunting back. After a few radio and cinematic interpretations of the same story (A Game of Death, notably, A Run For The Sun less so), many interpretations of bloodsports — in which men would kill other men for the entertainment of others as much as their own sport — would follow in the 70’s, like, Death Race 2000 and Rollerball. 1987’s The Predator was a heightened play on The Most Dangerous Game, while in the same year The Running Man (based on the Stephen King — aka Richard Bachman — 1982 novella) redefined the bloodsport as a game show, hybridizing both the hunt and the spectacle into one. Many more stories and films would follow, toying with these same concepts including the Jean Claude Van Damme illegal ring tournament Bloodsport in 1988 (sort of predicating MMA), while Hard Target (1993) and Surviving The Game (1994) had JCVD and Ice-T, respectively, as down-on-their luck men paid to be prey, and then, yeah, Mortal Kombat (the 1995 movie as much, if not more so, than the video game).

The Most Dangerous Game, the 1924 Richard Connell story of man hunting another man for sport on an island can be largely credited as the establishing point for all of this… death… that has occurred in the years to follow. The term “the most dangerous game” has, of course, become synonymous for a hunted man, since humans are just as capable of hunting back. After a few radio and cinematic interpretations of the same story (A Game of Death, notably, A Run For The Sun less so), many interpretations of bloodsports — in which men would kill other men for the entertainment of others as much as their own sport — would follow in the 70’s, like, Death Race 2000 and Rollerball. 1987’s The Predator was a heightened play on The Most Dangerous Game, while in the same year The Running Man (based on the Stephen King — aka Richard Bachman — 1982 novella) redefined the bloodsport as a game show, hybridizing both the hunt and the spectacle into one. Many more stories and films would follow, toying with these same concepts including the Jean Claude Van Damme illegal ring tournament Bloodsport in 1988 (sort of predicating MMA), while Hard Target (1993) and Surviving The Game (1994) had JCVD and Ice-T, respectively, as down-on-their luck men paid to be prey, and then, yeah, Mortal Kombat (the 1995 movie as much, if not more so, than the video game).

It was the Japanese film/novel/manga Battle Royale that exploded it all, seemingly combining elements of all the bloodsport material that predated it, plus thrusting teenagers into the mix, a nod to modern horror’s insatiable need to watch teenager’s die viciously. Battle Royale featured an institutionalized acceptance of the bloodsport set in a dystopian environment where a class of school children, picked by lottery, are sent to an island, forced to hunt and slaughter one another in penance for a previous generation of students’ country-wide walk-out. The popularity and influence Battle Royale seems even more expansive than The Most Dangerous Game, with Series 7: The Contenders (2001) the quickest to follow up, 2007’s “Stone Cold” Steve Austin vehicle The Condemned, and 2009’s Gamer. And then, of course, there’s The Hunger Games, whose explosive popularity is doubtlessly the impetus for each of these new comic book series hitting the stand, but the influence of Battle Royale is still be felt in every one of them.

While I haven’t read the first two issues, diving within the pages of issue three I cannot escape the Battle Royale or  Hunger Games comparisons in Avengers Arena. But then, you’re not supposed to. Most tellingly, the Avengers Arena‘s logo is a flagrant copy of the Battle Royale shield (as the cover to Issue 1 was a total cop of the BR poster), while the Greg Horn cover to issue 3 is a brazen pastiche of the flaming Mockingjay symbol from The Hunger Games empire. On the outside Marvel isn’t even trying to hide the fact that it’s just doing it all over again, and it’s no different on the inside either. It’s a shameless lift of the storytelling style and structure, complete with the character flashbacks interrupting the hunting sequences. It’s more Hunger Games PG-13 than “hard X” like Battle Royale since gone completely is the hardcore nudity and sex of the manga, as is the extreme gore. Where Battle Royale, in all its iterations, bathes quite happily in its provocativeness and its grindhouse attitude, Avengers Arena tries harder to make it more generally appealing, less brutal, less core.

Hunger Games comparisons in Avengers Arena. But then, you’re not supposed to. Most tellingly, the Avengers Arena‘s logo is a flagrant copy of the Battle Royale shield (as the cover to Issue 1 was a total cop of the BR poster), while the Greg Horn cover to issue 3 is a brazen pastiche of the flaming Mockingjay symbol from The Hunger Games empire. On the outside Marvel isn’t even trying to hide the fact that it’s just doing it all over again, and it’s no different on the inside either. It’s a shameless lift of the storytelling style and structure, complete with the character flashbacks interrupting the hunting sequences. It’s more Hunger Games PG-13 than “hard X” like Battle Royale since gone completely is the hardcore nudity and sex of the manga, as is the extreme gore. Where Battle Royale, in all its iterations, bathes quite happily in its provocativeness and its grindhouse attitude, Avengers Arena tries harder to make it more generally appealing, less brutal, less core.

I’m not a Marvel die-hard by any stretch, though I am a frequent dabbler. So it was interesting to open the cover to the front splash page, which lays out the series’ cast of teenage fodder and not recognize most of them immediately. X-23 and Darkhawk were the only ones I knew right away. Kid Briton I can assume is a Captain Britain Jr.-type, while similarly Bloodstone I imagine is a relative of Elsa Bloodstone from Warren Ellis’ Nextwave. And then there’s”Deathlocket”, the teenage female Deathlok, which made me burst out laughing, Other names I thought I should know: Cammi, Chase, Reptil, Nico, Juston… and after reading the book, turns out I do. Juston’s from from the great young adult Sentinel mini-series, Nico and Chase from Runaways (oh, duh), Reptil from Super Hero Squad, and Cammi from the Drax mini-series that led into Annihilation. Indeed, there are some fan-favourites among the C- and D-listers but no true A-listers in the mix (sorry X-23, you’re not even close), so they are truly all meat for the death game.

Cammi gets the spotlight this issue as the girl who fell from Earth, filling in some details on what exactly has happened to her since she disappeared from Drax’s side years ago. She’s turned into a pretty wicked little badass in Dennis Hopeless’ hands (from Keith Giffen’s template). It would appear that someone in the arena is attacking each of the camps in the middle of the night. Cammi is trying to suss out the offender, as is Darkhawk, and maybe a few others. Is it one of the “contestants” or is it an outside source? Given the “Murder World” subtitle, this is doubtlessly all a large production of the goofy carnival villain Arcade, but there’s no sign of him as a string-puller anywhere this issue. But what’s the point?

This is the defining aspect of Avengers Arena, however, that there seems to be little point, at least from only viewing this issue stand-alone. There’s nothing here to suggest larger purpose, especially if Arcade is involved. Jeb, in his review of issue one expressed utter fatigue of the Arcade conceit, that it lacks logic in the grandest sense (“with the power to casually overpower and capture every super-powered mutant in sight…”) whereas, for me, it is exactly that, a dismissable conceit for generally goofy entertainment. Still, Jeb is 100% right, particularly in this instance. Battle Royale had a deeply disturbed sense of satire, a commentary (if slight) about society’s perception of how youth should fit into its conform-or-die culture. Thin as it might have been, it was meaning enough to gleefully transcend as well as perpetuate slasher film tropes. Avengers Arena has no such platform. It’s just death strictly as entertainment and spectacle. A culling of the trademarks, perhaps as a means to see if any of them cause a big enough stir to elevate them in status.

I have to wonder where Avengers Arena goes in the end. Is it a limited maxi-series? Will there be a winner in issue 15, a last-man standing, or will the oppressed teens rebel and figure out exactly how to defeat the system they’re trapped in? Or do they all die and then Arcade starts it all anew? And where does Mojo play into all of this? Nowhere as far as I can tell, but I just thought I’d throw that entertainment obsessed other-dimensional freak into the conversation, since if he was bankrolling Arcade’s endeavor for some pan-galactic broadcast entertainment, it would provide the whole thing a little more… pizzazz ?). But then, that would be far too similar to what’s going on over in DC.

Introduced in the New Guardians Annual #1, the Tenebrian Dominion is a section of space under tyrannical rule, left isolated by the intergalactic police, the Green Lantern Corps, by some form of treaty. Carol Ferris, the Star Sapphire, after being summoned by the Zamoran leaders, is charged with leading a mission to enlist the help of Tenebrian leader Lady Styx. But in crossing into their space, she immediately breaks the treaty, and is captured and judged immediately as a spy, then forced to participate in the Running Man style game show, The Hunted, the most popular program on Glimmernet. The only difference here than most other survive-for-your-life type game shows is in this one they tell you in advance there’s no escape, no freedom in the end. You play the game, or you suffer, your family is sought out and they all take your place.

I’ve not been keeping up on the events of the Green Lantern collective, so I’m not certain what the set-up of this Annual (including a perplexing appearance from Kyle Rayner) was intending to accomplish. It certainly meant nothing to me as an outside reader and made little pains to explain it or draw new readers into the larger story it’s nominally a part of. It’s ultimately just a lead-in for the first arc of the new Threshold series, an attempt at capitalizing upon the popularity of the Lantern titles to hopefully drag a percentage of that readership over to the newly launched title. The New Guardians Annual effectively introduces the “The Hunted” concept (just in case you’re not already intimately familiar with it), as well as a new character, a rogue Green Lantern by the name of Caul, who is an even bigger dick than Guy Gardner ever was.

With Star Sapphire having responsibilities elsewhere in the DCU, she wasn’t really going to see The Hunted through to its logical conclusion, thus there’s never any real threat to her as a character, despite the fact her power is nullified in the deck-stacked-against-her competition. With a little help from Saint Walker and an aggressively overprotective Arkillo and not so much help from Caul and his unseemly associates, naturally Carol escapes, and as witnessed by the cover to issue one of Threshold, it’s no secret that Caul is her substitute.

Threshold #1 is more of the same, though instead of focusing on just one contestant as the Annual did, we see a few. Caul (oddly, for a fist issue, it depends far too much on the preceding New Guardians Annual to introduce his character) is chased through the streets, then aided by another contestant, Ember, whom he shuns. There’s also Stealth (from the old L.E.G.I.O.N. series) makes her New 52 debut, alongside the long forgotten Ric Starr, Space Ranger. Behind the scenes there’s a slug-like string-puller/program director who I have a hard time not seeing as a Mojo analog.

Threshold #1 is more of the same, though instead of focusing on just one contestant as the Annual did, we see a few. Caul (oddly, for a fist issue, it depends far too much on the preceding New Guardians Annual to introduce his character) is chased through the streets, then aided by another contestant, Ember, whom he shuns. There’s also Stealth (from the old L.E.G.I.O.N. series) makes her New 52 debut, alongside the long forgotten Ric Starr, Space Ranger. Behind the scenes there’s a slug-like string-puller/program director who I have a hard time not seeing as a Mojo analog.

Writer Keith Giffen is obviously familiar with the genre, evident by the fact that he wrote the English script for the Battle Royale Manga published by Tokyopop. His adaptation was controversial since he tossed in the spectacle of reality TV, its isolation of contestants, mimicking primarily Survivor (which in its own way is a muted play on The Most Dangerous Game). Threshold Presents: The Hunted is more of the same, Giffen recycling many of those same ideas in a sci-fi atmosphere, only this time foregoing the isolation angle and thrusting the hunt into the middle of the population (ala Series 7). Giffen’s had enough experience in the genre to find new quirks to inject without straying too far from the mold. There’s a bit of Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers propaganda satire in Giffen’s Glimmernet, the interstellar network that runs the Hunted, although the satire is largely absent. Unlike Avengers Arena, Battle Royale, or The Hunger Games, Threshold is more about survival. There’s fighting against the system, but it’s not fighting other contestants. They’re hunted, but have nothing to hunt back. It’s all about entertainment.

Paul Jenkin’s Deathmatch is a tournament of elimination bloodsport, Mortal Kombat style, instead of the isolated island or free reign iterations the others have taken. 32 of Earth’s “Supes” and “Fears” have been kidnapped, held in a facility completely resistant to their powers, and forced to face one another to the death. Of course we’ve seen this type of thing before, as far back as Secret Wars and as recently as the Terror Titans, but Jenkins has gone the mystery angle, keeping all the secrets, well, secret. How did they get there? With all their powers and skills, how can they truly be trapped? Who brought them here? Why are heroes so willing to kill one another, and why can’t they remember why? If the big “why?” surrounding Avengers Arena is in regards to its purposelessness, the questions posed in Deathmatch are of actual consequence. Issue #2 reveals that the contestants are exposed to some… truth, maybe… that compels them to fight, and to kill, and to survive. This isn’t mere game show, or spectator sport. There’s apparently something much more dire going on.

I had anticipated that Deathmatch would read like a rejected proposal for Avengers Arena, considering the timing  of the two books, but if that is indeed it’s origin, Jenkins has differentiated it dramatically with an insane amount of world and character building. Though he does include a “Who’s Who”-style character biographies in the back-matter, even without these simple-yet-richly detailed bios, Jenkins establishes relationships, character dynamics and histories within the story pages, and does so without relying upon archetypes. Oh, he uses archetypes, but only because they’re largely inescapable. Dragonfly is of the Spider-Man ilk, Sable a Batman type with Mr. Chuckles her Joker, Rat is Rorschach-like I suppose, and Meridian is a Superman. But unlike most comics who use analogs for the delight of ridicule or defamation, Jenkins uses them as a matter of shorthand to imply a massive history without requiring the actual history. Beyond this he rounds out the roster with enough original creations that the concept of analogs doesn’t seem so pervasive or distracting..

of the two books, but if that is indeed it’s origin, Jenkins has differentiated it dramatically with an insane amount of world and character building. Though he does include a “Who’s Who”-style character biographies in the back-matter, even without these simple-yet-richly detailed bios, Jenkins establishes relationships, character dynamics and histories within the story pages, and does so without relying upon archetypes. Oh, he uses archetypes, but only because they’re largely inescapable. Dragonfly is of the Spider-Man ilk, Sable a Batman type with Mr. Chuckles her Joker, Rat is Rorschach-like I suppose, and Meridian is a Superman. But unlike most comics who use analogs for the delight of ridicule or defamation, Jenkins uses them as a matter of shorthand to imply a massive history without requiring the actual history. Beyond this he rounds out the roster with enough original creations that the concept of analogs doesn’t seem so pervasive or distracting..

Dragonfly takes the role as grounding narrator in the first issue and continues through the second, providing perspective on what’s happening, background details or personal insight. In the first issue he is introduced standing over the body of his teammate whom he just killed, and his reaction to his deeds, his confusion over what drove him to such lethal extreme, gets straight to the heart of the book. There’s consequences to these death matches, and Jenkins does a fantastic job of providing them resonance. The deaths in these competitions mean something to the Heroes, sure, but even to the Fears it has an emotional impact.

While Avengers Arena seems to be keyed around a-death-per-issue pace, and Threshold: The Hunted seems more keen on establishing characters than killing them, Deathmatch manages to both establish more characters with more complexity and kill them off even faster. By the end of issue 2 only 23 of the original 32 contestants are still alive, with one death happening outside of the arena, in the commons, where that sort of thing shouldn’t be possible. The end of Deathmatch #2 unveils the whole first round line up of matches which doesn’t mean much to the reader, having little familiarity with the characters, but it has a noticeable impact on the people in the book.

All the books carry some great artists. Kev Walker doing some really tight work on Avengers Arena, his characters are unique and he has an amazing handle on drawing young characters distinctively. I also really like his facial close-ups, of which there are many, for which he manages to find unique angles and ways of showing a character’s face, but without being showy. Over on Threshold: The Hunted, Tom Raney returns (I don’t even recall the last time I saw his work) and he does a solid job of creating an alien urban environment for Caul to be pursued through, although for some reason his characters seem to have “kissy lips” (like they’re puckering up for a kiss) almost all the time. Then there’s Carlos Magno on Deathmatch who is going to explode as a talent in short order. His previous work on BOOM!’s Planet of the Apes series seemed the perfect match for him, an ornate fantasy setting, so it took some adjustment to see him put as much detail and creativity in a superhero universe. At first I couldn’t see it as a natural transition, but by the end of the first issue, I was sold. His greatest strength as an artist isn’t genre, but conveying the humanity of his characters, in their facial reactions and physicality. It’s all very natural, few overly dramatic gestures, no pushing the physical form for the sake of being “dynamic”. His art is just amazingly real, bringing superheroes down to Earth, like Dave Gibbons did in Watchmen.

Of the three, Avengers Arena is the most formulaic and the most familiar, but it nails the formula perfectly. It’s an impersonation of the Hunger Games and Battle Royale, but with Marvel Characters, like keeping the same engine for Mortal Kombat or Street Fighter but substituting DC or Marvel characters. Threshold: The Hunted, meanwhile, seeks to be lighter fare, as is Keith Giffen’s tendency as a writer. It’s not all about the death, it’s about entertainment, and Giffen knows how to entertain. In both cases, your mileage will vary depending on how you feel about the genre they’re playing in and how you feel about the characters involved. Deathmatch, on the other hand, lifted from the shackles of a shared universe, exceeds the genre in a way that is unexpected, by really establishing an emotional core, a cast of unique characters, a world, a competition and a mystery worth investing in beyond just wondering who will die.

Ratings:

Avengers Arena #3 – Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

New Guardians Annual #1 – Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Threshhold Presents: The Hunted #1 – Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Deathmatch #2 – Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

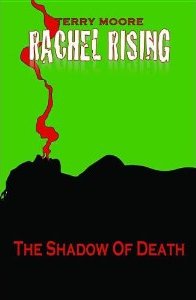

Rachel Rising #14 (Abstract Studio, $3.99)

Rachel Rising #14 (Abstract Studio, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Rachel Rising is a difficult series to review, or to recommend, in single issue form… but it’s one of my favorite current comics.

Terry Moore’s quietly evocative horror story has both thematic and structural links with his Echo and Strangers in Paradise, but moves at a more stately pace, revealing its secrets slowly, Moore’s specialty. But that slow burn means that any given issue will usually be a bad place to start reading (there’s no recap page, and expository backstory is nearly nonexistent); fourteen issues in, and we’re still learning more of just what the story is “about.”

Mind you, Moore’s phenomenal visual ability to capture the physical and emotional reality of his characters in his deceptively simple linework makes any given issue a visual delight, and Rachel Rising, with its wintry air of foreboding and punctuations of terrifying evil, is probably even better suited to black and white presentation than Moore’s previous series. Rachel Rising is also often funny as hell, and funny in that honest, personality-based way that Moore has made his own.

In other words, if you’re a fan of perceptive comic writing, great comic art, and ominously creepy horror stories, I can’t  recommend Rachel Rising too highly… however, what I recommend you do is seek out the first trade collection: Rachel Rising Volume 1: The Shadow of Death, collecting issues 1-6.

recommend Rachel Rising too highly… however, what I recommend you do is seek out the first trade collection: Rachel Rising Volume 1: The Shadow of Death, collecting issues 1-6.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars