Hollywood loves a good franchise. The movie-going public does too. Horror, action, comedy, sci-fi, western, no genre is safe. And any film, no matter how seemingly stand-alone, conclusive, or inappropriate to sequel, could generate an expansive franchise. They are legion. We are surrounded. But a champion has risen from the rabble to defend us. Me. I have donned my sweats and taken up cinema’s gauntlet. Don’t try this at home. I am a professional.

Let’s be buddies on the Facebookz!

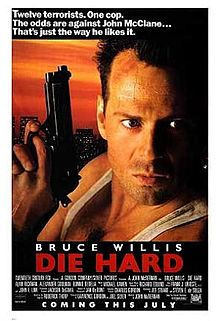

The Franchise: Die Hard: following the increasingly improbable misadventures of street-wise police detective John McClane as he repeatedly crosses paths with dangerous super-criminals. The series has spanned five feature films from 1988 to 2013.

The Installment: Die Hard (1988)

The Story:

John McClane (Bruce Willis), a rough-around-the-edges, ordinary-Joe cop from New York, has flown to Los Angeles to make amends with his estranged wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia), who moved to LA with their children to pursue her career at the Nakatomi Corporation. John is to meet up with Holly at Nakatomi Plaza, where the corporation is having their Xmas party. Both John and Holly hope their reunion will rekindle the marriage, but before they can make things work they get totally cockblocked by a heavily armed gang of international terrorists, led by one Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), who storm the Xmas party and take everyone hostage. Only John manages to escape. And he becomes a thorn in Gruber’s side as he slinks around the building, knocking off the terrorists one-by-one and making contact with the local LAPD. But the local authorities play right into Gruber’s hands, cause Los Angeles sucks. So it is up to John McClane to save the day, cause he’s from New York, which doesn’t suck.

What Works:

Die Hard is a film of subtle intelligence. I wouldn’t say it is a “thinking man’s action film.” Content-wise, what’s on screen is a goofy, good-times shoot’em’up that culminates in a giant explosion totally typical of its genre and era. It very easily could have been a fun but lesser film, propped up mostly by its high-concept — an Under Siege, if you will. The intelligence is all behind the curtain, in the film’s composition and construction. It is an intelligently made dumb movie. And it serves as a lasting example of what filmmakers can accomplish if they approach even lightweight material with a commitment to good storytelling.

Step one is the screenplay. In an alternate timeline, right now we might have been addressing installment #2 of the Joe Leland franchise. Leland was the NYPD detective hero of author Roderick Thorp’s 1966 novel The Detective, which was turned into a film starring Frank Sinatra. In 1979 Thorp wrote a sequel, Nothing Lasts Forever, about a now-retired Leland visiting his daughter in Los Angeles at her office highrise Christmas party, which is then attacked by a German terrorist gang. In 2013 this sounds like a nice set-up to a Liam Neeson-style old man actioner. But Sinatra was in his seventies by the time Hollywood got around to Thorp’s sequel, and in the decade of Arnold and Sly, unless your old man was named Harry Callahan, studios weren’t going to jump out of their seats over an action movie starring a retiree. But Thorp’s base concept about a cop coincidentally trapped inside a skyscraper with armed goons was an appealing one. Taking the highlights from Thorp’s book, such as Leland’s (renamed John McClane) memorable shoeless handicap, screenwriters Steven E. de Souza and Jeb Stuart fleshed out a deceptive antidote to the increasingly gonzo 80s action film. The brilliance of the concept is that Die Hard is hardly a small film, yet its contained location and semi-real-time pacing breeds it an immediacy and intimacy that intensifies everything. It isn’t small, it is compact. There are no hikes through the jungle. No musical montages. No car chases. In a way the entire film is like the final-battle section of a normal action film; the portion where our hero finds the villain’s base and storms it, ducking through hallways and whatnot. Every scene is propelling us forward, with swift consequences. And the movie also doesn’t need to resort to non-stop action. It is all between the lines. The less McClane is doing, often the more dramatic things get. When McClane gets a moment to himself, to “relax,” you really feel it. You’ve never been happier to see a fictional character bust out a cigarette to cool his nerves.

John McClane is a great character. Most of this has to do with Bruce Willis, but credit where it is due — McClane is also a textbook example of a perfectly established character. And Steven E. de Souza and Jeb Stuart accomplish it all with a magician’s slight-of-hand skill. The first time we see John McClane he is being a pussy, basically. We meet him in a close-up of his hand nervously clutching his chair’s armrest, while the airplane is landing. Not only do we see this, but the guy sitting next to McClane sees it too, and gives a wry comment about it: “You don’t like flying, do you?” It is an odd choice for introducing us to an action hero. But when McClane responds with a smirk – “What gives you that idea?” – in the span of a few seconds we’ve learned a lot. Showing McClane in a weak position lets us know he is no Arnold. He’s a regular guy. And he probably doesn’t fly much. His casual response lets us know he isn’t insecure about his flight anxiety either. He’s confident enough to laugh it off. So we still respect him as a “man.” This dynamic carries through for the entire movie. McClane gets scared. A lot. Which gives the action weight. But he’s always quick to smirk and make a joke out of it. His moments of fear make all his wise-cracking feel earned and prevents McClane from being a Bugs Bunny character who seems to know he is in a movie. (A viewing of Guy Pearce’s character in the recent Lockout should knock this idea out of the park for you.)

The entire first section of the film is loaded with fabulous slight-of-hand exposition. We learn McClane is a cop when his seat-mate spots his gun, which bypasses the need for a clunky exchange like, “So, what do you do?” or a scenario in which McClane needs to bust out his badge (which would undercut the idea that he’s on vacation by showing that he’s always ‘on the job’). The amazingly simple bit of McClane trying to find his wife’s name in the Nakatomi Plaza index, and realizing she must be using her maiden name, gives us about as much context on their relationship as an entire conversation might. Ditto with Holly telling her maid to prep the spare bedroom for a potential John stay, while nonetheless turning down the framed family picture in her office featuring John (which also has a genius payoff later when Hans turns the frame up and starts putting the pieces together). We also learn that McClane is a down-to-earth, meat and potato kind of guy through a few quick bits. McClane rides in the front of the limo that picks him up. He makes a disgusting face after drinking the presumably fruity cocktail he’s handed at the Christmas party. After a man kisses him on the cheek, McClane says, “Jesus. Fucking California.” But he says it with an amused smile. Though, of all the moments of set-up in the film, I think the moment when McClane truly clicks as a character and wins us over unequivocally, is after he has a fight with Holly and he’s left alone in the bathroom and says to himself, “Great job, John. Very mature.” He’s macho, yet flawed by his honest emotions. He’s not only sensitive to his own feelings and the feelings of his wife, but the whole idea of being a better man. Frankly it is an odd way to establish a hero who is about to start murdering fools with a machine gun. But that’s what makes Die Hard feel fresh, when in truth it is just more of the same. Through skilled filmmaking, we’ve been duped into thinking this superhero is a totally normal guy. The other big scene for McClane is the tearful goodbye message he gives Al (Reginald VelJohnson) to relay to Holly, in case he dies. A crying action hero is usually reserved for war movies. It is one of those humanizing decisions that could easily backfire. Tough guys don’t cry. Here it feels so right. It is probably the one scene that most launched Bruce Willis’ career too.

And we can’t ignore Bruce Willis’ contribution to McClane. Character set-up can only get you so far. Step two of Die Hard‘s intelligent production was the casting. Much has already been made of the outside-the-box casting of Willis, known to America at the time for the rom-com antics of TV’s Moonlighting. He was an odd choice from both logical casting angles for McClane. He didn’t seem like an action star, and he also didn’t seem like a dramatic actor. This was the guy who made his film debut in a Blake Edwards comedy. He was lazily charming; somewhere between the funny-laziness of Bill Murray and the macho-laziness of Robert Mitchum. That was his thing. But that’s what director John McTiernan and his producers must have realized was exactly what John McClane needed. Willis gives off a tired vibe without needing “I’m too old for this shit” dialogue. You just sense it. And no one smirks like Willis. It sounds silly to say, but smirking is very hard to pull off without looking like either an asshole or a doofus. Just look at Hart Bochner as office dickhead Harry Ellis (“Hans, bubby”), who was clearly cast because his smirking is both asshole-y and doofus-y. For a guy that no one thought could pull off being an action hero, Willis strikes a great pose in Die Hard. Not to help glamorize tobacco and firearms here, but, well, Bruce Willis looks totally awesome in the film — creeping around in his bloody wife-beater, clutching a gun and walkie-talkie with a cigarette dangling nonchalantly from his mouth. Come on. Enduring imagery like this is what motion pictures are all about.

So we’ve got our great hero, but the old maxim is that a movie is only as good as its villain, right? On paper, Hans Gruber isn’t as unique as McClane. When Gruber susses out Nakatomi executive Joseph Takagi, Gruber compliments Takagi’s suit, not only correctly guessing the London tailor, but noting that he himself has two such suits. After making a high-brow reference, he says, “Benefits of a classical education.” But the high-brow villain is nothing new, and dialogue-wise Gruber doesn’t hold a candle to baddies like Auric Goldfinger or North By Northwest‘s Phillip Vandamm. So the credit here goes entirely to casting, with the even more left-field choice of Alan Rickman, best known to American audiences from absolutely nothing. Action villains have been presented as effete or foppish previously, because regular slobs have historically enjoyed wallowing in homophobia. But Rickman isn’t foppish. He’s mannered. I can only imagine the Fox executives nervously scratching their heads watching his dailies, not even sure how to articulate the negative comments their brains are trying to hand them. Rickman just doesn’t seem like someone you use as this kind of villain. To put it uncreatively: he talks weird. He sounds like his voice-box is in his nose. He drawls, then clips certain words off with pursed lips. He does not sound cool. Yet… he sounds totally cool. The way Rickman says, “It’s not the police. It’s him.” Gold. He’s such a cool cucumber that we love watching McClane get under his skin. Rickman succeeds by being unusual, which is often all a villain really needs to stick in our minds. We’ve seen a million Hans Grubers. We haven’t seen a million Alan Rickmans. And it is as simple as that. And Hans Gruber has one of the most iconic villain deaths of the genre too — that slow-mo shot of him falling away from the camera, and down the long, long drop from the top of Nakatomi Plaza.

An addendum to this Gruber talk should include Karl (former ballet dancer and Soviet defector Alexander Godunov), one of the genre’s great sub-bosses, to use video game terminology. It isn’t unusual to make the most personal emotional beef be between the hero and the sub-boss, instead of the hero and the villain. But this is usually characterized by making the sub-boss a hothead whose buttons our hero keeps intentionally pushing, like Wilmer in The Maltese Falcon, or more recently Kid Blue in Looper. This allows our main villain to remain an intellectual equal with our hero, while still giving our hero someone to really piss off. But in Die Hard the connection between McClane and Karl truly is personal. McClane kills Karl’s brother. To Gruber, McClane is just “a fly in the ointment.” To Karl, this is a matter of true vengeance. “No one kills him but me,” Karl says. It makes sense to have Karl be the final death in the film, because the beef between McClane and Gruber was really just a matter of proximity. If Gruber got away, McClane wouldn’t have chased him down, and vice versa.

Die Hard manages a nice balance between Gruber and McClane fucking each others’ plans up — John always seems to be both winning and losing, which is very satisfying to watch.

Step three is John McTiernan. Unlike his gleeful bombast in Predator, here McTiernan presents an illusory simplicity. And does so with an enviable air of effortlessness. Die Hard comes off like a simple movie. Repeat viewings usually involve me forgetting how huge and ridiculous some of the action is. A lot of this is because McTiernan has the confidence not to oversell things. The movie is littered with set-pieces, but it is all presented as mere links in a steady chain of activity. Normally this is a bad idea for an action movie, where killer set-pieces can help gloss over the mediocre movie in between. But McTiernan knew he didn’t need to worry about that because he had a good movie on his hands. He can rely on McClane’s reactions and even missed opportunities, like the great moment in which McClane pulls the fire alarm, successfully summoning the authorities, only to see them turn their sirens off and turn around one-by-one after the bad guys convince 911 that it is a false alarm. We start to revel in the little things, small moments when McClane does something simple yet clever, or character bits, like McClane saying hello to the “girls” in a porno centerfold taped to a wall he keeps passing. McTiernan has a way of slipping into action pieces organically, not making a big deal of things, and that often has the effect of taking us not necessarily by surprise (we do know we’re watching an action movie), but allowing us to stay focused on McClane and not the action itself. One of the film’s action highlights is the scene in which McClane is using his stolen machine gun, and its shoulder strap, to dangle into an elevator shaft. It is a pretty basic moment, but its context in the film and how McTiernan stages it, it is epic. McClane’s forced to use his gun as a tool, and knowingly abandon it in the process. This makes the otherwise standard oh-no-the-rope-is-about-to-snap scene take on a whole new life. And the rising tension takes you by surprise, even though obviously we all know McClane will be fine…

Which brings me to another great aspect of John McClane and Die Hard‘s treatment of him. As with any main stream film, we know our hero isn’t going to die. So it isn’t unusual for action heroes to get injured in these movies. In fact, it is totally normal, even expected for your action hero to receive some abuse. But McClane feels disrespected by the film, for lack of a better word. It is a trait a lot of old film noir heroes had, always getting slugged in the gut by jerk-offs and conked over the head by femme fatales. By 1988 it was par for the course for action stars to take their shirts off, but McClane running around in his tank-top seems exposed. And making him shoeless is a stroke of genius. He is so vulnerable, in a rather demeaning way. In noir fashion, this also adds to the “I’m not even supposed to be here today” style humor too, with McClane bumping and bruising his way around the building getting just as exasperated by everything as he is scared. And again, a lot of this comes through in Willis’ performance more than anything else.

The plotting of the film – what gets revealed when and how – is handled well. Typically, the whole thrust of a film like this would be predicated by Gruber putting Holly in immediate danger. Interestingly, Holly is in no special danger for the vast majority of the film. If anything, Gruber seems to respect her, based on their limited interaction. Without the self-serving intervention of reporter Richard Thornburg (part of the hat-trick of uber-pricks William Atherton played in the mid-’80s, along with Ghostbusters and Real Genius), Gruber would never even have known that Holly was related to McClane, since even the smary Harry had the decency not to blow Holly’s cover. And the scene in which McClane and Gruber come face-to-face for the first time is a shrewd bit of farce, with the audience and Gruber fully aware of what’s happening, and McClane thinking that Gruber is one of the hostages — or does he?! Nope, he doesn’t it turns out. The filmmakers twist it up again, when Gruber finds out that the gun McClane gave him isn’t loaded. McClane is a smart cookie.

I don’t think McTiernan’s touch can be over-expressed here. It is important to remember what a completely absurd film Die Hard is in a lot of ways. Paul Gleason, as the Deputy Chief of Police, is playing the same kind of half-stupid blowhard he usually plays in comedies. But even he gets repositioned sympathetically when Robert Davi and Grand L. Bush show up as FBI Agents Johnson and Johnson. The Feds are cartoon characters, trigger happy, sociopathic and quippy, like leftovers from a Shane Black film. They say they don’t care if some of the hostages will die, and they seem indifferent to the execution of their own plans, eager to kill all the terrorists. There is nothing grounded about them. If they were in any more of the film than they are, they’d probably sink the whole thing by pushing Die Hard into parody. But McTiernan keeps it all together. Johnson and Johnson are still ridiculous, but it plays with the rest of the film. Mostly at least.

What Doesn’t Work:

Argyle (De’voreaux White), the young limo driver. In any other movie I likely wouldn’t give Argyle a second thought, but Die Hard isn’t any other movie. And Argyle demonstrates the dumb movie lurking beneath the film’s smartly put together surface better than anything else. He’s a cheesy character. Which is fine. The film is littered with cheesy characters. The problem is that Argyle serves no purpose. He exists solely as a comic relief cutaway, which the film doesn’t need when we have Harry Ellis, Richard Thornburg, the Deputy Chief of Police, Johnson and Johnson, and wisecracking John McClane himself. The cutaways to Argyle cluelessly talking to girls from the limo phone are funny. But you keep expecting that McClane is going to get down to the garage at some point, or need Argyle’s help. But he doesn’t. Argyle’s big “payoff” is foiling the Tech Nerd Henchman from leaving the garage, which is a moment contrived entirely to give Argyle a payoff. So it isn’t satisfying. Worse, scrawny Argyle knocking out a career criminal with a single punch is just stupid. Even for an ’80s action movie.

1988 was a different time. But Al Powell’s triumphant resolution just doesn’t sit well with me in 2013. Earlier in the film, Al and McClane bond as Al describes the traumatizing experience that took him off the streets and made him request a desk job — when he shot a teenager holding a toy gun. What keeps us liking Al after this horrible revelation is the intense remorse he feels about the accident. It caused him to change his life. Never again did he want to draw his gun on someone. Then, at the end of the film, Karl pops up out of no where (after we had thought McClane killed him earlier) and Al shoots Karl dead. Then, happy ending time. Since the ending of the film is happy, with silly Christmas music to boot, this isn’t meant as a moment of tragic comedy with Al now sinking even deeper into gun-guilt depression. No, the implication here is that Al gets his groove back. The events of the evening helped him get over the past shooting tragedy so that he can once again embrace using a gun…to shoot people. But, you know, shoot people who deserve it this time. That is a very 1980’s action movie sentiment. Al just helped save dozens of lives, using his wits and intuition. Isn’t that his triumph? Taking a desk job had made him feel like something of a half-man. Now he just got proof that he can make a big different without a gun and without hiding behind a desk. But that apparently wasn’t really the point here. It was sad that he had been discouraged from wanting to use his gun. Oh, 1980s, you’re incorrigible.

Overall Body Count: 20, plus an ambiguous two who maybe got blown up in an armored car.

McClane Kills: 10

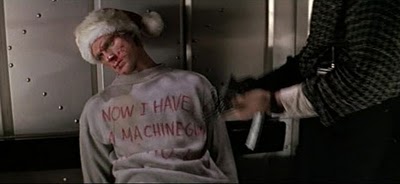

Best Villain Dispatching: After killing Karl’s brother, McClane sends the corpse down in the elevator in a chair wearing a Santa hat, with the words “Now I have a machine gun. Ho ho ho” written on the man’s chest.

Best Quip: [After the 911 operator tells him the phone line is for emergencies only]

McClane: No fucking shit, lady. Does it sound like I’m ordering a pizza?

Worst Quip: [While crawling through an air duct]

McClane: Now I know what a TV dinner feels like.

McClane’s Most Preposterous Feat: Jumping off the top of the building using a fire-hose as his safety line.

“Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker” Context: In response to Gruber’s question, “Do you really think you have a chance against us, Mr. Cowboy?”

Should There Be a Sequel: Sequel? What, is John McClane going to get stuck in another building around Christmas again and have to fight off more bad guys again? Don’t be silly.

Up Next: Die Hard 2

previous franchises battled

Alien

Back to the Future

Critters

Death Wish

Hellraiser

Home Alone

Jurassic Park

Lethal Weapon

Leprechaun

Meatballs

The Muppets

Phantasm

Planet of the Apes

Police Academy

Predator

Psycho

Rambo

Tremors