´

Part 1 (Navajo Joe) • Tim’s Review of Django Unchained

In the lead up to the release of “the best, most brutal, most intensely watchable film of the year” that releases on Christmas Day, I’m going to be running a five-part series called “Unchaining Django” that preps you for the film and celebrates Quentin Tarantino’s latest, greatest masterpiece (they all are, in some way or another) by looking at some of the films that led to it. Keep your eyes on CHUD each remaining Monday, Wednesday, and Friday until we all get to unwrap the season’s real gift on December 25th.

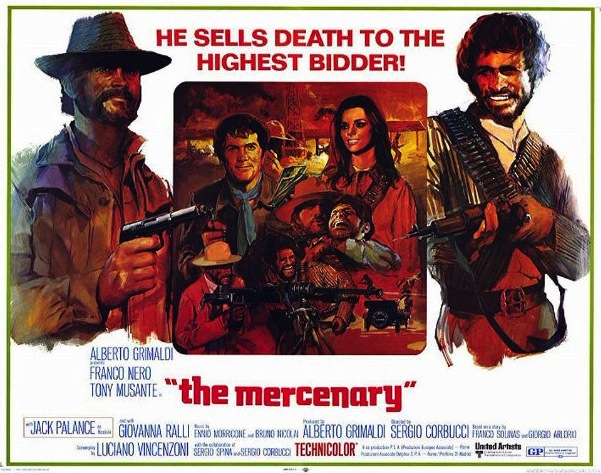

The Mercenary (AKA A Professional Gun)

We began our look at the films representing the DNA of Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained with a Sergio Corbucci film entitled Navajo Joe. That was a recommendation straight from the director’s mouth, and, in fact, the one film he chose when asked what western most demanded being seen before his own.

Today’s film is another of Corbucci’s ouvre, and I have it on good authority that The Mercenary was one of the director’s works that Tarantino and his D.P. Robert Richardson specifically studied before shooting Django Unchained. Contrary to Navajo Joe, this film does not offer as many obvious correlations and references to Tarantino’s films and instead represents an approach to stylizing a Western as well as an attitude that has clearly served as a big reference point for QT. It’s definitely worth taking a look, as it is yet another from Tarantino’s list of screened films that is available on Netflix’s Instant Watch, and is, once again, a damned fine Western in its own right.

Today’s film is another of Corbucci’s ouvre, and I have it on good authority that The Mercenary was one of the director’s works that Tarantino and his D.P. Robert Richardson specifically studied before shooting Django Unchained. Contrary to Navajo Joe, this film does not offer as many obvious correlations and references to Tarantino’s films and instead represents an approach to stylizing a Western as well as an attitude that has clearly served as a big reference point for QT. It’s definitely worth taking a look, as it is yet another from Tarantino’s list of screened films that is available on Netflix’s Instant Watch, and is, once again, a damned fine Western in its own right.

The Mercenary was released in 1968, in close proximity to one of Corbucci’s most well known films, The Great Silence. It features Django himself, Franco Nero (he knows the D is silent), playing a rather interesting Western protagonist, in that his deeds are not really any more slimy or less altruistic than other famous anti-heroes, and yet he’s infinitely less likeable than, say, ole Nameless Joe. Like many a central figure in Spaghetti Westerns, Sergei Kowalksi –or “The Polak” as he’s called– is driven by little more than profit and self-preservation. The thing is, where other heroes win our hearts through their sheer competence and stoic charm, The Polak is just kind of a shifty bastard. Once he gets hooked up with a Mexican Revolutionary who is on just this side of being a complete doofus, his opportunism becomes wrapped up in political conquest and the story begins in earnest. Half a dozen betrayals, escapes, Mexican standoffs, and army-scale shootouts later, the film reaches a conclusion that bears an uncomfortable resemblance to another famous Western climax, though it pays it off in its own unique way. Along the way liberal and joyous use of the +100 lb. Hotchkiss M1914 machine gun stacks the body count impressively high for a non-Peckinpah Western. Even better than the violence is perhaps a string of black humor evident in the film, most hilariously manifested during a scene in which Kowalksi details the dynamics of revolution and the socio-economic status of Mexico using the extremely clunky, bizarre metaphor of woman’s anatomy, with a naked, sleeping prostitute as a visual aid.

It’s also worth noting that Jack Palance is featured in The Mercenary, and if The Polak doesn’t necessarily get you rooting for him, in contrast with Palance’s character he’s the coolest guy to ever fire a six-gun. Palance’s waxy features and perpetual creepy smirk make him a great villain, though he only pops into the movie at a few key moments.

Ultimately we’re here to relate the film to the upcoming release at hand. With that in mind, first up it should be mentioned that, though The Mercenary isn’t as silly with things you’ll recognize from Tarantino’s films, there are definitely a couple “ah-ha!” moments in store.

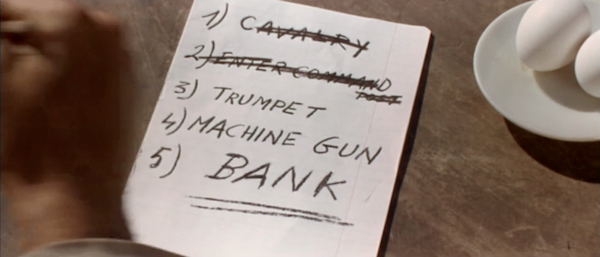

Not least among them is this familiar image:

Not the first or last list in a movie, but something about the big bold scratch-outs and general lack of subtlety might ring a bell…

Ennio Morricone was a frequent collaborator of the lesser-known (though not lesser-talented) Sergio and, like Navajo Joe, fans of Kill Bill will find a few familiar, major cues originating from this ’68 film.

As for what to look for in the film that might prepare you for the tale of Jamie Foxx’s Django, the influences are mostly in style. You can perhaps spot some very nascant seeds of Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) and Django’s partnership in the pairing of The Polak and Paco the revolutionary, but aside from a general mentorship dynamic, it’s kind of a reach. Paco is all dim-witted energy and revolutionary spirit while Kowalski is leeching and exploitive. That said, this is still the story of a relatively imparcial outsider gaming a political struggle for his own benefit, only to find himself tied to a social underdog and his struggle to upend the system.

If there is perhaps one element of Django Unchained that shines the brightest it is the beautiful, nuanced relationship at its core, with the truly benevolent –if merciless– Schulz taking at first a professional interest in the fiery Django, before being taken in entirely by the later’s righteous fury and ruthless competence. It’s a dynamic relationship between two sophisticated characters, and together the pair represent some of the best writing Tarantino has ever composed. It’s on a whole different level from what drives The Mercenary, but the basic shades of the dynamic are there…

Stylistically there is more to appreciate in Corbucci’s visualization of The Mercenary, with some of the most beautiful use of elaborate camera work and exuberant zooms that you’re likely to see this side of a Spielberg or Shaw Brothers movie. Shot after stunning shot impresses with crane work and amazing blocking way ahead of its time, including an awesome 360º pan early in the film. It’s the kind of brilliant work that makes you wonder how Corbucci has never gained the notoriety of Leone. It also makes it completely obvious why Tarantino has latched onto the director as such a huge influence on his own filmmaking.

There is a healthy dollop of political themes running through The Mercenary, earning it a place among the “Zapata Westerns,” a Spaghetti subset referring to Westerns dealing with the Mexican Revolution. It’s perhaps a little too cavalier to say anything to profound about such a conflict, but there is a shamelessness with which the film revels in the annihilation of the Mexican military establishment at the time, while simultaneously portraying the revolutionaries as fuckups destined to be caught up in their own pillaging before being stomped out. This is something the film shares with Django Unchained, which is equally shameless about the violent, bloody, joyous path its title character carves through the Plantation-era South. That said, Tarantino again layers on his own deft handling of tone so that the political subtext pays off as satisfyingly as the violence.

Since this is another film so readily available, I’ll go ahead and cut it here and encourage you to queue this sumbitch up and watch it for yourself. A familiarity with the common grammar of Corbucci films will certainly ripen your enjoyment of Tarantino’s Christmas gift this year, so by all means pre-game with some Nero action.

Meet me here Wednesday for the third installment!

Thanks for reading!