The Crow: Skinning the Wolves #1 ($3.99, IDW)

by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Aside from having seen only the first film, I’ve only ever heard about The Crow. As more series have spun out of the first, the idea seems to have changed from a personal story the creator James O’Barr created to process the death of his fiancee into a sporadic series of tales about a Spectre-like supernatural avenging spirit, following the disparate tales of people who have suffered wrongful deaths or traumas and are given the power to exact vengeance. This latest series takes place during the second World War, in a concentration camp, which is an appropriate enough setting for the concept.

This being my first foray into this world, I can’t say what, if anything, this brings to the mythology of The Crow, but I can say that I never felt lost. O’Barr’s script is a pretty good example of letting the story unfold from the perspectives of its characters. Prior knowledge of the nature of underlying concept is completely unnecessary to enjoy the story, which is a rarity in “new reader friendly” serial comic books. O’Barr is also not phoning it in here: this feels like less of a return to his most popular concept than it does a story that he genuinely wants to tell. It’s a small story, but it has a feeling of authorial weight and ambition behind it, but the story hasn’t really aired its themes yet. Still, it is very well written (despite a niggling factual error about a great opera), and it seems that this series has something yet up its sleeve.

Jim Terry’s art is an appealing combination of EC horror and Joe Kubert’s Sgt. Rock. The book gets off to a quick start with some breathless action. It some feels kinetic, immediate, deliberate, and distant all at once, like Charles Bronson gunning down the bounty hunters at the beginning of Once Upon a Time in the West. Terry’s art comes more into its own once the action cools down, however. It feels like he’s finding these characters as he goes along. The faces of the principles early on are somewhat non descript, but each individual begins to form more of identity as the drama takes center stage, as if stepping out of a fog.

For all of the skill on display, The Crow: Skinning the Wolves feels a bit typical. It fits snugly into the modern tropes of the modern “historical revenge” sort of fantasy that industrial scale suffering seems to have unleashed on our culture, and its voice is a little too reliant on an early 90s Sandman sort of vibe. Still, the book manages to satisfy, and while there are some elements that feel very derivative, it manages to avoid the cliche.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb (Hill and Wang, $22.00)

Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb (Hill and Wang, $22.00)

by Graig Kent

I’m not much of a history buff. I don’t forget the past, so I’m not condemned to repeat it, as the Santayana quote goes, I’ve just taken little effort to explore it beyond the broader strokes. I know about World War II, the Cold War, and as a child of the 80’s the arms race and images of nuclear holocaust kept me awake at night. I’m familiar with the Manhattan Project pretty much in name and purpose only, I really had no idea how the atomic bomb (or rather, bombs, since the Manhattan Project resulted in two different designs: Little Boy and Fat Man) came into being. It’s a story I’ve never looked into, because I’ve never thought about it. Atomic bombs are just something that have always been there in my lifetime. Everpresent. Ominous. I know they were created during the second world war, and I know the basic excuse as to why they were used in Japan, even still I didn’t know the particulars and I never really questioned it too much.

Jonathan Fetter-Vorm’s Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb is a beginners guide to the Manhattan Project, atomic science, and the end of WWII, but it’s also brilliant in its conciseness. Fetter-Vorm on our behalf has read and understood a wide swath of those monolithic, presumably dull history texts, so as to present as accurate as possible a portrait of what happened inside the Manhattan Project, and hit home the greater impact it had. We get a sense of the personalities involved from both the military and scientific angle (Groves and Oppenheimer especially), we also are exposed to the conditions under which the bomb was built, the security measures put in place, and the impact on the wartime economy (in its existence it employed tens of thousands of individuals, with billions in 1940’s currency invested in its creation).

Fetter-Vorm does an immaculate job of parsing out a lot of raw data in a gripping narrative though avoiding storytelling. By providing analogies to simplify concepts he is able to explain casually nuclear fission, and quantify the capacity for destruction. Equally he understands visual storytelling and his sequences for the first atomic bomb test and the deployment on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki are all intense and heart-wrenching. His illustration and execution of these sequences made my stomach crawl, revealing the upper limit of humanity’s capability for destruction. There’s no patriotic glory to the proceedings, just the sobering details of man perhaps obtaining knowledge that’s beyond his capacity to utilize conscientiously.

Trinity is a flat-out brilliant read, a raw, captivating, thought provoking text perfect for those like myself: aware, but ignorant. It’s so effective at dispensing historical information without being overwhelming, and at being thoroughly engrossing, it should be a staple of Grade 9 history classes everywhere. Though not conventionally a story, Fetter-Vorm establishes himself here as a masterful visual storyteller, and his structured narrative is so well assembled, it’s treads close to being unbelievable were it not so potently real.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Avengers Arena #1 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Jeb D.

This new comic from Dennis Hopeless and Kev Walker combines a pair of pop-culture artifacts that I’m fairly tired of: “Battle Royale” emulation, and the supervillain Arcade.

Battle Royale, of course, is the Japanese manga/movie phenomenon where teenagers are turned loose in the wild to hunt and battle each other to the death, for the entertainment of bourgeois gawkers. A blood-soaked mashup of The Most Dangerous Game, Mortal Kombat, and Lord of the Flies, it has gone on to inspire plenty of adaptations and knock-offs (Hunger Games being just the most obvious), and is usually cited as being some kind of metaphor for societal ills; personally, it’s always seemed less like a metaphor, where the reader is invited to make connections between two ideas or objects, than a simile, where the author states the comparison explicitly. And that sort of on-the-nose storytelling is already too common in corporate superhero comics, without digging out a model as blatant as Battle Royale or Hunger Games (the “inspiration” is even acknowledged in bits of metatextual dialog, and the cover’s overt aping of Battle Royale).

But that’s the setup Hopeless gives us: a clutch of teen mutants (mostly Avengers Academy students, their numbers rounded out by a few that are new to me) find themselves on a mysterious island, their purpose to battle each other to the death, at the hands of Arcade… who, for me, is the second of the book’s conceptual toe-stubbings.

Back in the 80’s, when the X books were characterized by the wrenching emotional ups and downs of storylines like Dark Phoenix, Days of Future Past, and the predations of the Hellfire Club, Arcade’s “Murderworld” appearance was an amusing diversion, with Arcade himself a garishly-dressed misfit with a knack for over-the-top puzzles and traps; a Silver Age throwback, rather like a pre-Moore/Miller version of the Joker. But he’s as one-note as supervillains get, and each of his appearances carries with it the need to ignore the fact that a guy with the power to casually overpower and capture every super-powered mutant in sight can’t think of anything better to do with it than… well, than to casually overpower and capture every super-powered mutant in sight. And while that kind of thinking wasn’t as problematic in the days of Stan Lee and Julie Schwartz, it just feels tedious in today’s environment.

Hopeless does what he can with the concept (I have no idea if he pitched it himself), and works to use the dialogue to distinguish the various members of his team of teen cannon fodder, but unless there’s some truly fascinating backstory to be unfolded over the next few issues, I’m having trouble caring one way or the other, particularly since the early “flash-forward” to the last day of the contest suggests a pretty linear progression.

Artist Kev Walker, with colors from Frank Martin, turns in a perfectly serviceable issue, given what he has to work with; appropriately dark and gloomy, and for those looking to see heroes rewarded for their nobility by being blown to smithereens, he gives good gutpunch. He also underlines Hopeless’ character-driven dialogue with some strong facial work.

Whatever virtues stuff like Battle Royale and Hunger Games may possess, Hopeless and Walker seem content just to let you know they’ve read them (or are at the very least aware of them), rather than growing or expanding upon the “inspiration.” It’s not impossible that there’s a grand plan underlying this comic that will reveal itself in future issues, but I’ll take the risk of missing out on it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Change #1 ($2.99, Image)

Change #1 ($2.99, Image)by D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Before I start this review in earnest, I just have one request for genre media: Can we please retire Lovecraft for a while? We all love his ideas and his stories, but tentacled eldritch gods having steadily been becoming a crutch for science fiction and horror lately. I get the appeal. Lovecraft traded on Pascal’s famous quote, “These vast empty spaces fill me with dread.” Pascal needed God to fill those spaces, except what if there was something living in those vast empty spaces that was hungry and didn’t care? It’s a thematically compelling idea, and I can understand the allure. But when we co-opt it for our own narratives, which tend to be vastly different in theme and tone, are we really adding anything comprehensive or powerful to our own stories, or are we merely aping an aesthetic?

Thankfully, Change manages avoid this aping in ways that are… difficult to describe. It has the feel of an old Vertigo book, but punchier and more aggressive. Think about what it would be like if Robert Altman collaborated with Grant Morrison on Short Cuts, and you get the picture. The plot follows three very different people, all connected for as yet unknown reasons to some unknown purpose (It does involve a random-feeling giant Lovecraft monster, hence rant). But Change seems less concerned with being a story than it does with being an unhinged experiment in creativity. Ideas and elements come out at a dizzying rate, making the book feel like a fever dream rather than a story per se.

Somehow, it kind of works, but all of the reasons that the book provides to like it also provide reasons to dislike it. Creators Ales Kot and Morgan Jeske are obviously furiously talented, but we have yet to see whether they are capable of honing their ideas into something more coherent. Or more original. For every new idea that comes out of this book, there is an old one right along with it. For every risk, there is a cliche, which makes it a hard book to really judge.

If you are willing to forgive some pretty egregious faults, Change is an exciting rush of artistic ideas, but damn if it isn’t hard to fully recommend.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

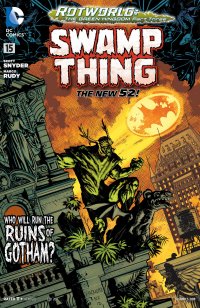

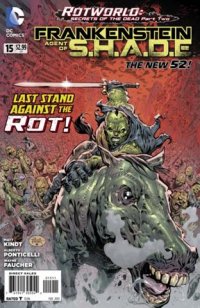

Rotworld Run-down

Animal Man #15, Swamp Thing #15, Frankenstein: Agent of S.H.A.D.E. #1 (DC, $2.99 ea)

by Graig Kent

Events at DC of late — and we’re talking creative team shake-ups, firings, etc, rather than the typical “gathering-of-heroes Events” that take place in comics — have brought to light much of how the publisher is operating its New 52 lineup. If it wasn’t apparent enough during its tumultuous first year of publishing, the recent firing of Gail Simone off Batgirl (via email no less) has made it readily apparent that editorial, not creative talent, is ruling the roost. It’s seems very much that if you don’t play ball with the grander plans editorial has for its trademarks, you’re out, and that the luxury of fulfilling one’s creative vision is reserved only for the select few.

Rotworld is an “Event” (of the “gathering-of-heroes” sort), and equally a capital-E “Epic” that has been the sole focus of both the Animal Man and Swamp Thing titles since their inception. Writers Jeff Lemire and Scott Snyder seem to be (alongside Grant Morrison and Geoff Johns) the only golden children in DC’s writing stable, and much of the success of Rotworld is a result of their friendship and extensive collaboration on the overall concept prior to (and continuing after) the launch of the New 52. As well, it’s evident they have had complete editorial buy-in from the get go, with minimal interference along the way, letting Rotworld come to full fruition. It helps that in permitting both of these immensely talented writers the freedom to construct and pace their books in their own (shared) vision, they’ve made two languishing properties very successful, and in turn that unexpected success has raised the profile of each book.

There was a planned synchronicity to the first year of both Animal Man and Swamp Thing that culminated in the crossover of the two titles at the end of that first year. Lemire in Animal Man had been exploring the idea of “The Red”, a metaphysical concept in which all animal life is connected, while in Swamp Thing Snyder explored “The Green”, a similar concept in which all plant life is linked. Each has explored, to different degrees, the third part of the triumvirate, “The Rot”, the force of decay that is in constant opposition with The Green and The Red. Typically there is a balance between three, or rather, The Green and The Red keeping The Rot in check, but the avatars of these two forces, Buddy Baker and Alec Holland are young and inexperienced in the larger conflict that they’re faced with. It was during the Animal Man/Swamp Thing crossover that Baker and Holland made a critical mistake by diving deep into The Rot for the final confrontation with the big bad, only to find that the avatar of The Rot, Arcane, had not only prepared for their gambit, but had orchestrated it. The result found Baker and Holland removed from society for years, though to them no time had passed when they emerged to find their loved ones gone along with the majority of society. In their absence, The Rot took over.

There was a planned synchronicity to the first year of both Animal Man and Swamp Thing that culminated in the crossover of the two titles at the end of that first year. Lemire in Animal Man had been exploring the idea of “The Red”, a metaphysical concept in which all animal life is connected, while in Swamp Thing Snyder explored “The Green”, a similar concept in which all plant life is linked. Each has explored, to different degrees, the third part of the triumvirate, “The Rot”, the force of decay that is in constant opposition with The Green and The Red. Typically there is a balance between three, or rather, The Green and The Red keeping The Rot in check, but the avatars of these two forces, Buddy Baker and Alec Holland are young and inexperienced in the larger conflict that they’re faced with. It was during the Animal Man/Swamp Thing crossover that Baker and Holland made a critical mistake by diving deep into The Rot for the final confrontation with the big bad, only to find that the avatar of The Rot, Arcane, had not only prepared for their gambit, but had orchestrated it. The result found Baker and Holland removed from society for years, though to them no time had passed when they emerged to find their loved ones gone along with the majority of society. In their absence, The Rot took over.

DC has long steeped itself in its own unique mythologies, prominently the Lords of Order and Chaos (Hawk and Dove, Dr. Fate) and the Elementals (Swamp Thing, Firestorm, Red Tornado). Beyond retaining the “emotional spectrum” of pre-New 52 Green Lantern, the trio of The Green, The Red and The Rot is the first such representation of higher order in the new DCU. Primarily confined to these two titles, and left in the hands of eager collaborators, the mythology has emerged richly structured with a solid foundation, and remains undiluted.

Though the wrapping of Frankenstein in the two seems a bit of an afterthought within the Agent of S.H.A.D.E. title  itself, that Lemire wrote its first 8 issues before passing the chores along to his friend Matt Kindt, there was obviously an advance idea of how Frank would fit. As a creature made of undead flesh brought back to life, Frank is resistant to The Rot, making him a perfect ally. Invariably the series does wind up dovetailing into the event nicely. Kindt has diverted the series from it’s established “Agent of S.H.A.D.E.” track — which was, in hindsight, a derivative of the Hellboy/B.P.R.D. relationship (though no less enjoyable) — to partake in Rotworld, which means the series will unfortunately conclude next month before Rotworld has reached its conclusion and without much connection to where it began.

itself, that Lemire wrote its first 8 issues before passing the chores along to his friend Matt Kindt, there was obviously an advance idea of how Frank would fit. As a creature made of undead flesh brought back to life, Frank is resistant to The Rot, making him a perfect ally. Invariably the series does wind up dovetailing into the event nicely. Kindt has diverted the series from it’s established “Agent of S.H.A.D.E.” track — which was, in hindsight, a derivative of the Hellboy/B.P.R.D. relationship (though no less enjoyable) — to partake in Rotworld, which means the series will unfortunately conclude next month before Rotworld has reached its conclusion and without much connection to where it began.

The post-apocalyptic future setting, since “Days of Future Past”, is a staple of the superhero genre, but rarely is it presented as part of something even larger, and not just as a story in and of itself. Rotworld is the summation of over a year’s worth of comics for the two key titles involved, during which Snyder and Lemire have managed to keep their books independent of one another (besides the crossover that led into it)… independent but complimentary. One could easily read only Swamp Thing or only Animal Man and understand the complete saga of each character, but together they do form an even greater picture, expanded in scope by the inclusion (rather than shoehorning) of Frankenstein. It’s obvious that some sort of time traveling or “only a dream” mumbo jumbo will need to occur in order for this all to correct itself since the rest of the DCU is just carrying on otherwise (unless there’s a huge reveal that Animal Man, Swamp Thing and Frankenstein inhabit an alternate earth from the bulk of the New 52) but at this stage, mere months away from their endgame, the writers have earned some level of trust.

The collaboration of the writers, artists and, yes, even editors has yielded a rare and unique anti-crossover event that easily distinguishes itself from the more put-upon crossovers DC has had, including the far less collaborative events like Court of Owls, Death Of The Family, H’el On Earth, The Culling and the myriad of forced crossovers (Suicide Squad/Resurrection Man, JLI/Firestorm, I Vampire/Justice League Dark etc. etc.). Its patient set-up was perhaps a little drawn out, but it’s rather interesting to see not just one book in the New 52 but a pair of them with a long-term plan that is allowed to see it through.

Rotworld: Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars