Audio version included below.

If you will, imagine a vast room from the ceiling of which hangs a thousand light bulbs –all of different shapes, sizes, colors and brightnesses– and as you walk through the room the bulbs, one by one, gently light up from all directions. Imagine some of these bulbs merely glimmer with a soft light while other shine brilliantly and boldly, and that together they create a beautiful incandescence, a warmth. A bit melodramatic though the metaphor may be, I suspect most fans of cinema would have no trouble likening it to the experience watching their favorite films and enjoying as each new idea or wonderful moments lights up something within them. In this case it is certainly the closest I can come to describing the specific experience of watching Cloud Atlas, the epic, incredible new movie from filmmakers Lana and Andy Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer.

It is the joy of a great movie for every scene, every shot, every moment to carry with it some delight, some realization of design, or art, or creativity that fires off a happy neuron in one’s mind, or brings a thrilled breath to one’s breast. Though always working subtly, Cloud Atlas is a movie made for those moments. It the year’s best film- a sublime experience, and not like anything you’ve ever seen before.

It is the joy of a great movie for every scene, every shot, every moment to carry with it some delight, some realization of design, or art, or creativity that fires off a happy neuron in one’s mind, or brings a thrilled breath to one’s breast. Though always working subtly, Cloud Atlas is a movie made for those moments. It the year’s best film- a sublime experience, and not like anything you’ve ever seen before.

Cloud Atlas is an adaptation of the 2004 David Mitchell novel of the same name, which is celebrated for its exploration of grand themes by way of small stories, as well as its unique, palindromic structure that divides six stories in twain, leading with the first halves and following with the second halves in reverse order. Here the filmmakers truly adapt the novel to the screen, transforming the uniquely literary devices of the novel into the uniquely cinematic devices of the film that reinforce the ideas of the former, meanwhile adding new ideas and a new potency that comes when words become corporeal.

Fixated on the idea of “eternal recurrence,” this film is built on the the stories of an agent of a slave plantation, a brilliant early 20th century composer, a 70s-era journalist, a modern literary editor, a cloned woman of the future, and a tribal man of the post-world, with each story told in an interwoven narrative that moves scene-to-scene and sometimes shot-to-shot through all of them. Like the instruments and motifs in a symphony, stories wax and wane in prominence with a stunning delicateness, creating a narrative that’s not quite like any other ever put to screen. Even better it’s a narrative that is exciting, poignent, and interested in the very biggest ideas and dilemmas mankind struggles with, exploring them through action, adventure, drama, romance, and outright fun.

If most parallel narrative films are like a highway –with a film’s focus shifting between distinct lanes from sequence to sequence– then Cloud Atlas is more akin to a flowing river through which the narrative flows and its focus voyages effortlessly. This paired with a casting structure that weaves an ensemble of great actors through a multitude of roles creates a story that captures something grand, something magnificent- the idea that all things are connected, that human history is a series of echoing events. The intricacy of the tapestry the Wachowskis and Tykwer weave to convey that idea is stunning- this is certainly among the most richly and acutely engineered films of the last decade, perhaps ever. This richness and details permeates every level of the film- the structure of the script, dialogue, casting, performance, make-up, costume design, art direction, prop design, lighting, editing, pacing, blocking, composition, sound design, and music composition all contribute to this cinematic symphony.

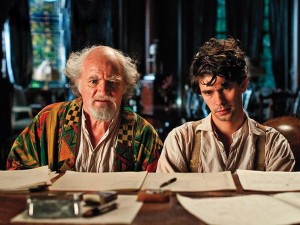

The instruments themselves –which is to say the excellent cast that includes Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Ben Wishaw, Jim Broadbent, Jim Sturgess, Doona Bae, Hugo Weaving, Hugh Grant, James D’Arcy, Keith David, Susan Sarandon, and Zhou Xun playing more roles than could ever be reasonably listed here– are all finely tuned, and deftly move through different keys and octaves in the sense that any given actor is as likely to play a role as another, regardless of race or gender. Some transformations are obvious, some buried beneath deep make-up, and the appearances in the stories may be as fleeting as appearing in a photograph or among a crowd of people. Tom Hanks is naturally the anchor of the film, and his star power is definitely on display as he plays men of honor, of wickedness, of wisdom, and of primitivism with equal care. Bae, Sturgess, Wishaw, Berry, and Broadbent all achieve something special (sometimes outright excellence) in their major roles, while familiar faces like Weaving, Grant, and David turn in characteristically rich supporting turns.

As for the behind-the-camera team, The Wachowskis are no strangers to shaking up cinema by its foundations, having irrevocably contributed to cinematic linguistics with their reality-bending vision in 1999’s The Matrix and the sequels that followed. Though ground through the memetic commoditization of pop cultural parody and imitation, bullet-time was a true show-stopper, and one that fundamentally altered the imagination of its audiences. Even more recently the siblings quietly advanced the grammar of the virtual camera by leaps and bounds with their classic Speed Racer (undoubtedly among the most undervalued films of the last decade), all while recognizing that a humanistic, well-told story is the bedrock on which all of this visual and structural innovation must sit. Meanwhile, since Run Lola Run Tom Tykwer has been persistently looking for ways to tell untellable stories, with his 2006 Perfume: Story Of A Murder another among this century’s films that haven’t gotten their due. Combing their powers, The Wachowskis and Tykwer represent a team with more groundbreaking ideas than one film could possibly handle, were they not so willing to push the limits of the form on every level.

As for the behind-the-camera team, The Wachowskis are no strangers to shaking up cinema by its foundations, having irrevocably contributed to cinematic linguistics with their reality-bending vision in 1999’s The Matrix and the sequels that followed. Though ground through the memetic commoditization of pop cultural parody and imitation, bullet-time was a true show-stopper, and one that fundamentally altered the imagination of its audiences. Even more recently the siblings quietly advanced the grammar of the virtual camera by leaps and bounds with their classic Speed Racer (undoubtedly among the most undervalued films of the last decade), all while recognizing that a humanistic, well-told story is the bedrock on which all of this visual and structural innovation must sit. Meanwhile, since Run Lola Run Tom Tykwer has been persistently looking for ways to tell untellable stories, with his 2006 Perfume: Story Of A Murder another among this century’s films that haven’t gotten their due. Combing their powers, The Wachowskis and Tykwer represent a team with more groundbreaking ideas than one film could possibly handle, were they not so willing to push the limits of the form on every level.

It’s impossible (and unnecessary) to dissect exactly where the influences of each filmmaker begins and ends, though it’s possible to find DNA from all of them in the gorgeously reticulated script. Undaunted by the “unfilmmable” nature of the novel, the three broke the prose down to its tiniest fragments, reconstructing from scratch the streaming narrative in such a way that pairs similar incidents and climaxes between the stories together. So, for example, the film moves between, say, moments of revelation for two different characters before juxtaposing two other characters proving themselves, followed by an action sequence that is complemented by the energy of three others sporadically glimpsed during the action. The actual directing of the segments largely represents straightforward sophistication- every segment (even a giant scifi chase sequence) merges with the others perfectly, directorial flare always foregone in favor of consistency of overall vision.

In terms of writing and editing, the film is nothing short of brilliant, with gifts that will reveal themselves over years and dozens of viewings. Perhaps your first showing you’ll note how a color shows up in multiple stories or that a fleeting moment of levity in one story actually foreshadows the entire, horrifying nature of another, while your third viewing will reveal the way two specific stories link up and complement each other emotionally. The film is so dense that it’s almost worthless to present a specific example- like trying to illustrate the majesty of the Great Barrier Reef by holding up a single piece of coral. A comparison from nature is apt too, as for all the precise filmmaking and nearly architectural engineering put into the script, there is an organic texture coating the film.

In terms of writing and editing, the film is nothing short of brilliant, with gifts that will reveal themselves over years and dozens of viewings. Perhaps your first showing you’ll note how a color shows up in multiple stories or that a fleeting moment of levity in one story actually foreshadows the entire, horrifying nature of another, while your third viewing will reveal the way two specific stories link up and complement each other emotionally. The film is so dense that it’s almost worthless to present a specific example- like trying to illustrate the majesty of the Great Barrier Reef by holding up a single piece of coral. A comparison from nature is apt too, as for all the precise filmmaking and nearly architectural engineering put into the script, there is an organic texture coating the film.

Still, it’s impossible to not look at, say, the story of Sonmi~451 in Neo Seoul and not see that it almost perfectly recreates the first act of The Matrix (complete with a unknowingly enslaved pod person being led outside of their platonic cave by an attractive figure, caught, interrogated by Hugo Weaving, escaping, discovering the true, hideous nature of the world by an African-American spiritual leader, all in a scifi action story), and think the filmmakers weren’t interested in very deliberately infusing the idea of “eternal recurrence” into every molecule of their film, even in a meta-textual sense.

The majesty of Cloud Atlas will not resonate with everyone –no truly remarkable film ever has– while others may find details like the ever-present make-up or the sometimes silly degraded English spoken in the post-apocalypse too much for them. The film is not without its clumsy moments and borderline sanguine choices, but those that don’t miss the painting for the brushstrokes will see unfold before them a film like no other. The Wachowskis, Tykwer and the cast and crew brave enough to join them endeavored to do battle with convention, with the studio notion that audiences find comfort in cliche, and with that nasty blockbuster filmmaking habit of deprioritizing script for spectacle. With all of the effort, engineering, and outright love put into the film, for it to result in such a brilliant succes reminds one of the Sun Tzu quote, “and thus do many calculations lead to victory.”

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

AUDIO: I’ve added the audio version of the above review, if you’d rather listen than read to my big block of text (as I’ve done with Cosmopolis and Lawless before). This whole audio thing is still in beta, so forgive the slightly tinny audio (it’s not too bad, and totally listenable) and my occasional stumble. I recorded this one in a hotel room beneath the thick comforter to block out as much A/C sound as possible, so I start experiencing light asphyxiation there towards the end.

Also, I’m going to start adding some podcast-like monologue talks after the reviews. So if you want to hear me talk about film stuff some, it will be there, but you won’t have to skip through the first fifteen minutes of neurotic talking (and a dildo ad) before you hear what you actually came for. Thanks guys! Again, let me know if you dig this so I know whether or not to keep going!