It’s a great challenge, attempting to turn a bigger-than-life marble statue back into a man, and not just delivering a cheap imitation or a still thoroughly marmoreal movie character. Director Steven Spielberg and his partner-in-biography Daniel Day Lewis have not only attempted, but thoroughly accomplished exactly that with Lincoln, which turns the apotheosized politician, father, husband, and lawyer back into a flesh-and-blood-and-flaws human being without failing to capture his legendarily magnetic way. It is the kind of movie that could have been all sorts of different films and still the only real conversation would have been the performance at its center, so Spielberg made an interesting choice- he shot a political heist film that’s virtually nothing but performance.

It’s a great challenge, attempting to turn a bigger-than-life marble statue back into a man, and not just delivering a cheap imitation or a still thoroughly marmoreal movie character. Director Steven Spielberg and his partner-in-biography Daniel Day Lewis have not only attempted, but thoroughly accomplished exactly that with Lincoln, which turns the apotheosized politician, father, husband, and lawyer back into a flesh-and-blood-and-flaws human being without failing to capture his legendarily magnetic way. It is the kind of movie that could have been all sorts of different films and still the only real conversation would have been the performance at its center, so Spielberg made an interesting choice- he shot a political heist film that’s virtually nothing but performance.

While stopping short of a full on Lincoln’s 11-style romp, Spielberg certainly rolled with a script from Tony Kushner that adapted Team of Rivals: The Political Genius Of Abraham Lincoln into an often amusing tale of back-room zigging and zagging where it’s a winner-takes-all fight to pass the 13th Amendment. Involved are a bevy of morally heavy questions and personal dilemmas –is it righteous or monstrous to lie to Congress and risk protracting a bloody war to forever destroy an institution of atrocity?– and obviously the various tragedies in Lincoln’s life weigh heavily on the spirit of the film, but it’s also an entertaining one that is more concerned with the rich texture of exchanges between politicians and the strategic politickin’ that it took to get anything done, much more a constitutional amendment.

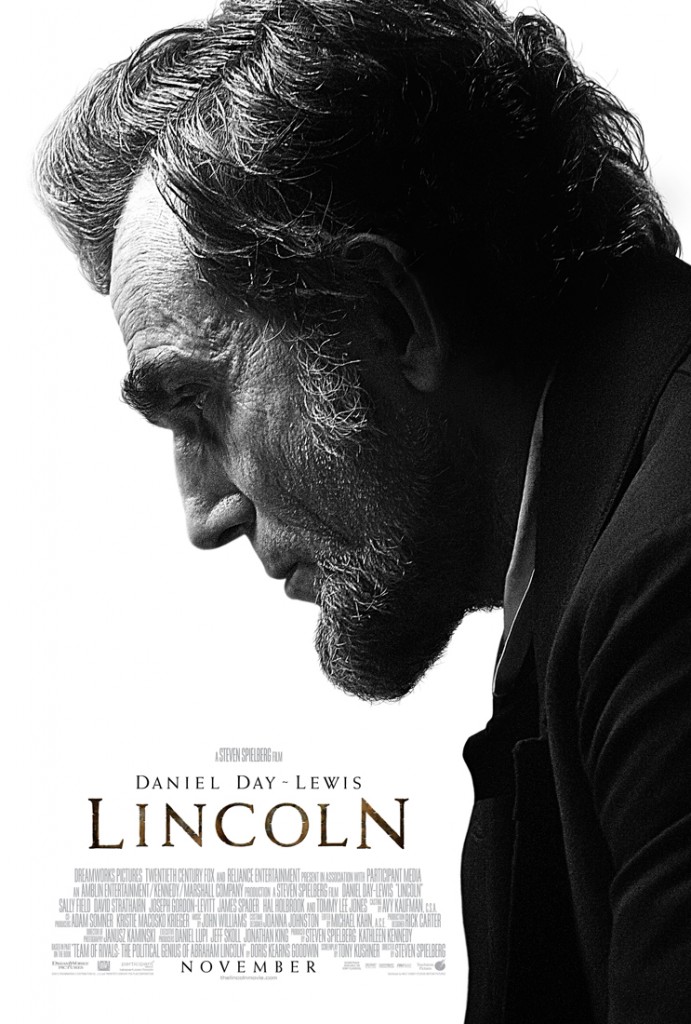

Taking place in the months immediately before the end of the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination, Spielberg’s political thriller deliberately avoids turning Lincoln into a speechifyin’ figure very deliberately. The film opens with a scene shortly after the Gettysburgh Address, and has people other than Lincoln reciting it. This acknolwedges the legend of Lincoln that is still with us today, makes it clear that a recently re-elected Lincoln is himself fully aware of his stature in the Union, but avoids blowing him out of proportion early. We even first see him sitting and out of focus as the camera fixates on another character. From there unfolds a performance that is utterly, completely captivating, and perhaps the most magnetic characterization of a character in the actor’s long, storied career that is already filled with many all-time performances. Daniel Day Lewis’ performance is sure to be counted among some of the greatest film acting ever captured, both for his perfect handle on the wit and soul of Lincoln as well as his stunning embodiment of the passion of the times.

From perfectly inhabiting the spindly yet densely strong frame Lincoln was known for, to finding a vocalization and manner of gesticulation that accentuates the reality as documented, Day Lewis is Lincoln through and through, faultlessly conveying exactly how Lincoln built a reputation for being such a captivating speaker. Right away, the start of Abe telling a story is enough to make the characters around him knowingly throw up their hands, and by the end of the film it’s made clear why. Lincoln was –and in this film is– a man who deliberated and convinced through story, who illustrated ideas and countered objections by laying out anecdotes that bolstered the logic of his decisions, and Lincoln is portrayed as a decision maker if nothing else. It takes some kind of genius to portray a genius, and Daniel Day Lewis has it. It’s entirely believable that the man inhabiting Spielberg’s film would be able to maneuver a cabinet of former political opponents and a Congress of lame ducks who have stomped out abolitionist legislation before to doing something unprecedented to alter the fundament of the country.

Alongside Daniel Day Lewis is David Strathairn as his loyal secretary of state, and a massive batch of brilliant character actors that range from guys like Walton Goggins, Jackie Earle Haley, and Michael Stuhlbarg with brief roles, to people like Tommy Lee Jones and Sally Field who play key roles in Lincoln’s life, both political and personal. There are spotty accents (I’m sad to say Stuhlbarg and Jared Harris are among those) and punchline parts, but there is no real weak link in this massive period ensemble, and it’s this that allows Spielberg to pull off dueling tones- the captial D drama and the levity of much of the politics. Where in some films such bouncing back and forth might create too much dissonance, the humor here is largely couched in the highfalutin wit of the times, with congressmen hurling overwrought insults and predatorial characters like James Spader’s WN Bilbo preying on dumb House representatives with confident smarm.

Being a political opera and a high-stakes morality tale if anything, few if any characters go through any sort of change or growth. This is a story of righteous men grappling with what they see is a moral certainty and turning it into a reality. Rather than “arcs”, well-timed glimpses into how Lincoln’s relationship with his wife and sons played out shortly before his death create the effect of a painting becoming more and more detailed. And while they don’t represent an arc per se, some of the film’s most quietly triumphant moments are those in which Lincoln ponders a question aloud and reaffirms his beliefs for himself and those around him.

Being a political opera and a high-stakes morality tale if anything, few if any characters go through any sort of change or growth. This is a story of righteous men grappling with what they see is a moral certainty and turning it into a reality. Rather than “arcs”, well-timed glimpses into how Lincoln’s relationship with his wife and sons played out shortly before his death create the effect of a painting becoming more and more detailed. And while they don’t represent an arc per se, some of the film’s most quietly triumphant moments are those in which Lincoln ponders a question aloud and reaffirms his beliefs for himself and those around him.

Putting Lincoln into the “heist” genre is accurate enough, as that is a kind of film in which its characters rarely change, and is in fact the nature of the mission that goes through an arc. In this case the United States itself, as reflected by the character of its leaders, is at a crossroads. The mission is to make sure that an inevitably ending war leaves the country with a foundation of freedom and without an attachement to the system that took it to war in the first place. You can perhaps narrow this down to a few key House reps that do or do not find their courage to do the right thing, but ultimately this is a game of chess, and the audience’s satisfaction is invested in finding out how exactly the game was played that led to victory.

Aesthetically, this is top-notch work. Spielberg and Kaminski capture a distinct period look by going for a sort of gorgeous realism, with undramatic exteriors contrasting extremely dramatic interiors lit by sunlight that gushes forth from windows and lights up dusty air. This speaks to an ecosystem in which the real drama takes places behind closed doors, where decisions are made and deals struck, whereas the open-air is for the gilded political theatre of stump speeches and ceremonies, or the stark, ugly reality of battle. The way Spielberg captures things has changed, as he’s moved past his style of complex set-ups and camera moves to a more straightforward, deliberate kind of coverage. Political theater and somber reflection lend themselves to this kind of filmmaking, even if it does feel like a certain Spielbergian spark is lost in the man’s work these days.

Though it inherently trades on our knowledge of the outcome and our fascination with a long-sainted figure, Lincoln is a great achievement. Spielberg has captured a great President as a great cinematic figure, and Daniel Day Lewis has turned the marble into a man. The film is gorgeous, moving, and entertaining, and it lives up to the hopes many have built up for a project so many years in the making. It is one of the very best films of the year, but, more importantly, as Lincoln himself now belongs to the ages, so does this film, and it is good enough that it may very well survive them.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars