I’ve included an audio version of the review below, if you’d prefer to take this aurally.

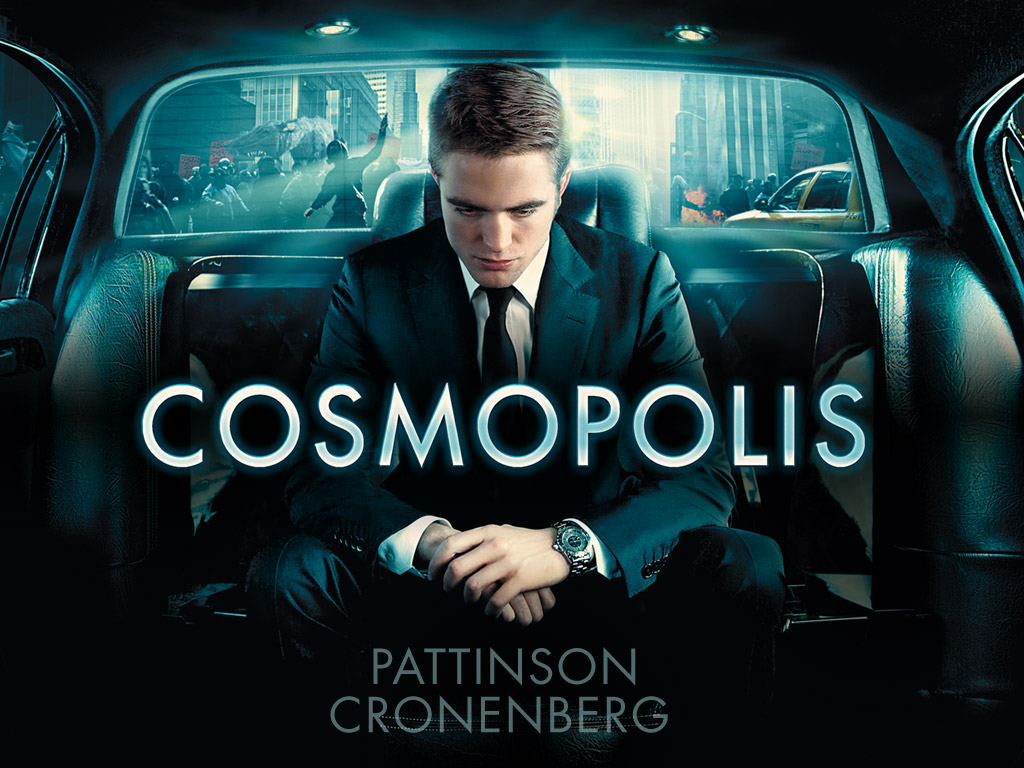

If Cosmopolis is any indication, David Cronenberg is back to giving as few fucks about what anyone thinks a movie should be than he has before at perhaps any time since his Naked Lunch days. An occasionally bizarre, always surreal trip through a wickedly detached billionaire’s social and business circle, Cosmopolis is a story content to float atop liquid philosophical meditation, heading in whatever direction the ideas flow. In other words, discard your expectations of set-up, development, and climax and prepare yourself for a film that is simply going to happen to you, as it noshes on the prescient musings of Don DeLillo on topics like cyber capital, business, classism, sex, art, and human evolution.

A synopsis truly is a fool’s errand, as the story progresses by no traditional means, and instead progresses by virtue of what interesting places Pattinson’s Eric Packer sees out of the window, or what new person suddenly happens to be be in the limousine with him. Conversations flow and we gradually learn about different layers of this character, who waxes between being a cypher representing pure capitalism to an intensely personal and idiosyncratic character. Pattinson’s work here is the stuff of turning a metaphor into a man and back again, and the young actor is game for every bit of it. Cronenberg leads him to a place of cold vulnerability, and the resulting performance anchors the director’s staccato, theatrical filmmaking.

A synopsis truly is a fool’s errand, as the story progresses by no traditional means, and instead progresses by virtue of what interesting places Pattinson’s Eric Packer sees out of the window, or what new person suddenly happens to be be in the limousine with him. Conversations flow and we gradually learn about different layers of this character, who waxes between being a cypher representing pure capitalism to an intensely personal and idiosyncratic character. Pattinson’s work here is the stuff of turning a metaphor into a man and back again, and the young actor is game for every bit of it. Cronenberg leads him to a place of cold vulnerability, and the resulting performance anchors the director’s staccato, theatrical filmmaking.

For Cronenberg’s part, he’s continued deeper down his road of improvised, straightforward filmmaking, but at the same time has lept back into the surreal. Gussied up with little in the way of the visually grotesque (there is some), Cosmopolis is all about a tone of disconnect. The director has built his career on characters that are either decidedly or by nature distaˇnced from the world, and despite an oeuvre peppered with pirate TV programmers, hiding former mobsters, high-level scientists, the kinky, the insane, and other hyper-fringe character, in Packer Cronenberg may have found his most isolated hero yet, despite keeping him surrounded by the scrutiny and outrage of the public. Anarchy is shut out by the cork-lined, steel-reinforced doors of the limo, which for the audience manifests as a film that is often without the audio bed of light atmospheric sound design that usually soothes us into a scene on a deep psychological level. Instead there is nothing by air and conversation, and the latter is thick and esoteric while the former is charged with the electricity of literary prophecy.

While the the novel on which this film is based was written pre-’08 economic crash, the film has the luxury and joy of hindsight, lending a greater wait to its long discussions of what cyber capital means to the world, to nature. Our protagonist is losing his multi-billions by the minute, having miscalculated the most minute financial detail after a long career of successful investment gambling. With the imbalances DeLillo theorized about in his book having proved prescient in a big, big way, Cosmopolis the film is almost a victory lap for the surrealists and social doom-sayers.

While the the novel on which this film is based was written pre-’08 economic crash, the film has the luxury and joy of hindsight, lending a greater wait to its long discussions of what cyber capital means to the world, to nature. Our protagonist is losing his multi-billions by the minute, having miscalculated the most minute financial detail after a long career of successful investment gambling. With the imbalances DeLillo theorized about in his book having proved prescient in a big, big way, Cosmopolis the film is almost a victory lap for the surrealists and social doom-sayers.

Where Cronenberg’s fidelity to the source material becomes strange though, is in its characterization of the masses and their anger, of the class division. Here angry mobs blindly attack limo’s containing the rich, spraypainting and shoving, following them down the street. It’s a pre-Occupy, pre-social media conceptualization of protest, and it is even more marked later when Paul Giamatti enters the film to point a gun at Pattinson. Represented is an older generation of the laid off former employees, the betrayed loyal, rather than the generation that can’t even find its first job to be fired from. The film feels a little out of time in that regard.

Protest and anger no longer fester and accumulate until they can’t be contained and result in a march of a million men or the like, now they start small, sit immobile, and grow virally, as the like-minded coalesce around the more gravitational force of discontent. Like science fiction that envisioned the far out destiny of the CRT monitors and combustion engines, DeLillo’s text doesn’t predict the paradigm shift to come, and the film stays true to that outmoded perspective, even to its ending that fixates on and punctuates the film with the class stuff. All that said, a sequence involving a sort of prankster activist feels extremely timely– the best social critiques cut deep enough to be timeless after all. It’s no coincidence this scene may be the most condescending of any.

This monotone, sometimes off-putting film isn’t entirely without lots of dark humor, sex, violence, self-mutilation, ambiguity and prostate exams to spice things up, and though Cronenberg captures it all with a mostly invisible hand, he doesn’t fail to visually heighten things where it matters. Through shots that are a little too high, a little too close, a little too long, and blocking that’s just a little too theatric, he keeps us on edge and ensures that his mirror to society isn’t too relatable- the film is in a universe of its own. Hell, just casting Kevin Durand ensures everything’s going to feel a little off.

This monotone, sometimes off-putting film isn’t entirely without lots of dark humor, sex, violence, self-mutilation, ambiguity and prostate exams to spice things up, and though Cronenberg captures it all with a mostly invisible hand, he doesn’t fail to visually heighten things where it matters. Through shots that are a little too high, a little too close, a little too long, and blocking that’s just a little too theatric, he keeps us on edge and ensures that his mirror to society isn’t too relatable- the film is in a universe of its own. Hell, just casting Kevin Durand ensures everything’s going to feel a little off.

If Pattinson’s excellent work often relies on restraint, it’s usually necessary as he’s bombarded with such a broad range of supporting turns, including Sarah Gadon’s straight-out-of-Gatsby coolness, Gouchy Boy’s vulnerable thugging, and Samantha Morton’s professorial musing. Pattinson participates gamely in these scenes, and though it’s all muted by that Cronenbergian distance, you still see the energies, depressions, intellectual curiosities, and disgusts broil beneath the Twilight star’s surface. This is a grown up performance; one as mature as the very grown up — if not gratuitous — sex he’s miming with Patricia McKenzie. It’s also foolish to witness an actor go toe to toe with Paul Giamatti in an extended scene of almost pure performance without appreciating that there is real talent fueling the core of this star.

Cosmopolis is not a film designed to be consumed, digested, and fully appreciated in one sitting. Like A Dangerous Method, the density of the dialogue alone necessitates a few laps around the track. Suffice it to say the film is definitely weird, interesting, and good in a very loose sense of the word. This should be more than enough for most fans of Cronenberg’s work or of experimental cinema in general, but get back to me in a decade or so and I’ll tell you how just how good it is.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

…or whatever.

Audio Version*:

*After recording, I added the words “lots of dark humor” to the antepenultimate paragraph, just so ya know. Also, I did this for shits and giggles, and it’s not a perfect, NPR-ready reading. If anyone out there like the audio version being included, let me know and I’ll keep doing it and refining them.